Snowpack update: sorely needed pattern change

Plus, SnowSlang: P is for "penitentes," and sweet relief at Telluride

The West has received a desperately needed jolt of fresh snow in recent days, and more flakes are in the forecast.

But the outlook for this season remains troubling across much of the region because we dug such a deep hole over the past few months, with several states and numerous monitoring stations recording their lowest snowpack levels in decades.

At the snow.news headquarters near Durango, we picked up about 11 inches from Tuesday night to Wednesday night thanks to the long-awaited pattern change. Another significant storm is set to arrive tonight.

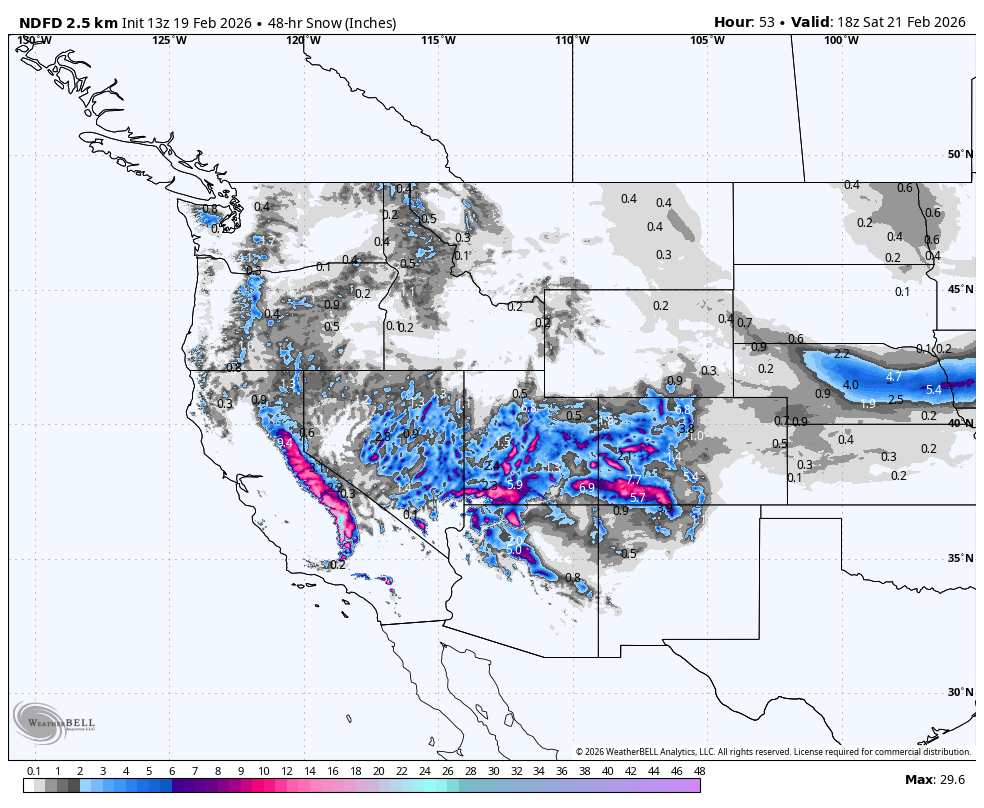

The map below shows snowfall over the past 72 hours, with the highest totals in the Sierra Nevada—the site of an avalanche catastrophe I discuss below.

Looking ahead, here’s the National Weather Service forecast for snowfall over the next 48 hours.

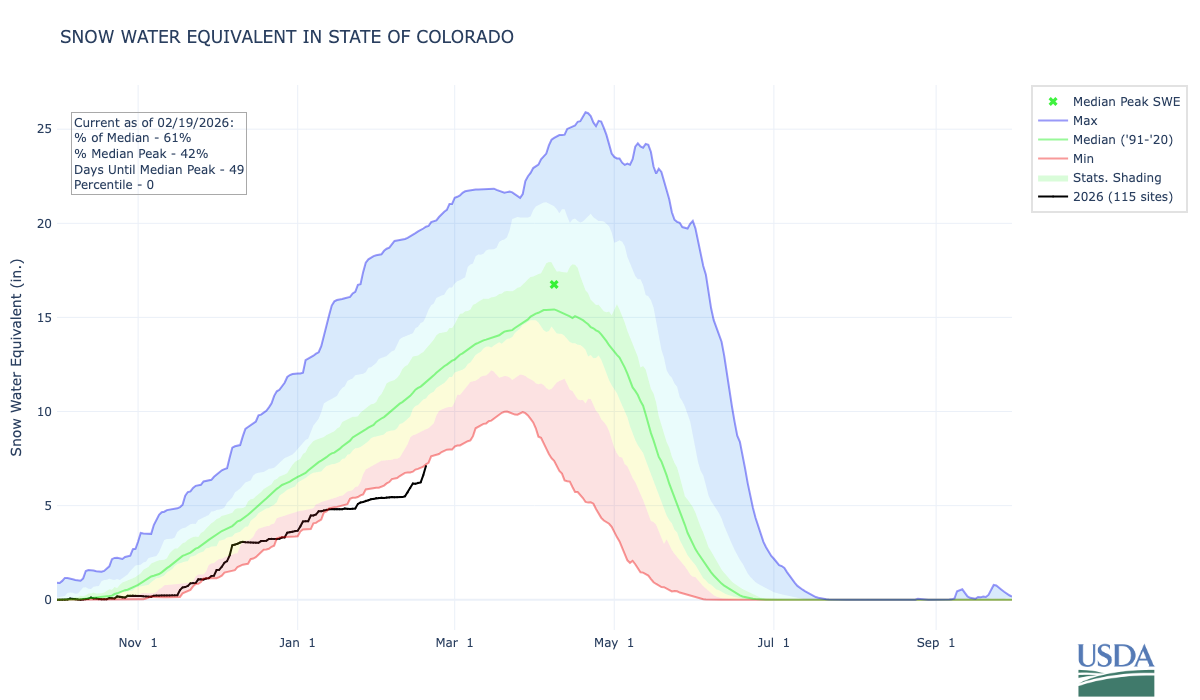

The storminess has boosted the snow water equivalent—a measure of the snowpack’s water content—in many river basins in the West. But the map below shows that conditions by the end of yesterday remained far below normal across most of the region.

Here in Colorado, for example, data from this morning shows that the statewide snowpack (black line) has risen in recent days, but it’s still at a record low. With seven weeks to go until the median peak date of April 8, Colorado’s snowpack is just 61% of normal (1991-2020 median).

In Utah and Oregon, which also recently hit record lows, the situation has improved slightly. Utah’s statewide snow water equivalent is now at the 4th percentile and 64% of the long-term median. Oregon’s snowpack, which has only 35 days to go until its median peak on March 25, has edged up to the 2nd percentile and 35% of normal.

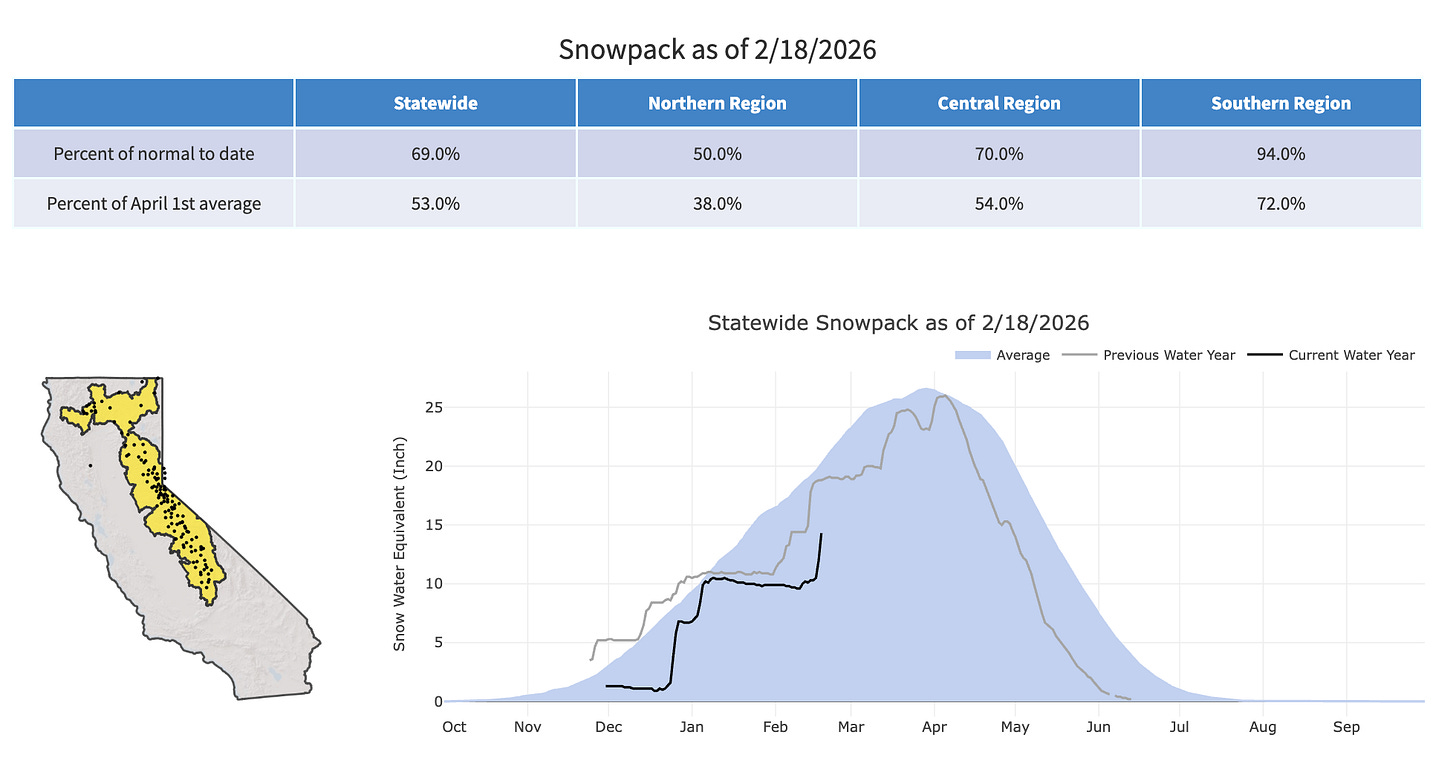

The most dramatic rebound in the region has occurred in California. The black line in the February 18 chart below shows a sharp rise after days of heavy snow, yet the statewide snowpack is only 69% of normal and 53% of the April 1 average.

The onslaught of snow offers a bit of good news for the West’s water supply, but the severe weather led to disaster in California’s Sierra Nevada, where an avalanche claimed the lives of at least eight backcountry skiers (a ninth person is presumed dead). The incident is the deadliest avalanche in modern California history, according to The Los Angeles Times.

In a 2024 post, I examined and visualized data on avalanche fatalities, using information from the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) and Bruce Tremper’s Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain.

Since 1950, the highest annual death toll from avalanches was 37 in 2021, according to CAIC. But in five of the years since 2015, fewer than 20 died across the country, so the loss of nine individuals in one incident is staggering.

Historically, February has been the deadliest month for avalanches. The most common activity was backcountry touring (337 deaths), followed by snowmobiling (310 deaths). As shown in the map below, California ranks eighth among Western states (including Alaska) for avalanche deaths, with Colorado’s notoriously sketchy snowpack claiming the most lives by far.

If you’re finding this useful, consider subscribing to snow.news for future updates — it’s free.

SnowSlang: P is for “penitentes”

SnowSlang is my occasional look at the language of snow. More at snowslang.com.

Snow can be a real shape-shifter. One of its most intriguing forms: the spire-like pinnacles known as penitentes.

Found in a few high-altitude locations, penitentes resemble blades of snow and derive their name from their resemblance to “penitents,” the procession of religious adherents in Spain and Latin America who wear white robes and pointed hoods during Holy Week while atoning for their sins.

Sometimes referred to as “nieves penitentes” to emphasize their association with snow (nieve in Spanish), the columns were first scientifically described by Charles Darwin during his 1835 travels in the Andes.

Darwin didn’t fully understand how penitentes form, but modern science offers a good explanation.

When the sun beats down on snowfall in the cold, dry, thin air of places like the high Andes, the snow can sublimate and convert directly from its solid phase into water vapor without first becoming a liquid. Irregularities in the snow cover cause some areas to disappear (ablate) faster than others, creating depressions amid ridges. The pattern of shadows and solar radiation causes the ridges to sharpen and the troughs to wither away, leading to a collection of spiky snow formations.

Solar radiation is the key driver, and penitentes respond by orienting themselves according to the sun’s angle. Because they’re all pointed in the same direction, they appear like a procession of natural snowmen.

As these pictures suggest, penitentes have a strange, almost otherworldly feel. In fact, scientists believe that similar structures exist on other celestial bodies in our solar system.

Europa, a satellite of Jupiter that has an icy crust on top of what’s believed to be a liquid ocean, may have penitentes up to 15 meters (49 feet) high, according to a 2018 study in Nature Geoscience. Scientists are keenly interested in exploring Europa since its liquid water could potentially harbor life, but the paper notes that “penitentes could pose a hazard to a future lander on Europa.”

Farther afield in the solar system, Pluto may also be home to penitentes, although they’d be made of methane ice rather than water. In 2015, when NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft passed by Pluto, it captured images of a spiky landscape that could have formed via the same process that plays out on Earth.

Our planet’s penitentes exist in an exceptionally harsh environment, yet they’re still able to support life. At an elevation of more than 17,000 feet, scientists found thriving communities of microbes, according to a 2019 study in Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research.

“In this environment penitentes provide both water and shelter from harsh winds, high UV radiation, and thermal fluctuations, creating an oasis in an otherwise extreme landscape,” the researchers wrote.

The landscapes that support penitentes on Earth may provide analogues for conditions on other planets and moons, helping scientists understand how life may persist beyond Earth.

“Our study shows how no matter how challenging the environmental conditions, life finds a way when there is availability of liquid water,” Lara Vimercati, lead author of the study, said in a press release.

Sweet relief: powder at Telluride

To my eye, Telluride wins the prize for Colorado’s most scenic ski area. The competition is stiff—and I’m always willing to do more research—but the views from the top are tough to beat. In every direction, breathtaking mountains rim the horizon, and the glacially carved box canyon that cradles the town isn’t too shabby, either.

I had the good fortune to ski Telluride over Presidents’ Day weekend, and I hit the slopes after 13 inches fell in the prior 72 hours. It’s been a tough season for Telluride, not only because of meager snowfall but also due to a ski patroller strike that temporarily shut down the mountain.

With a roughly 40-inch base, the snow cover was still relatively thin, but I released a ton of pent-up turns and was thrilled to show my wife and daughter some of my favorite trails. Below are a few photos from the trip: