SnowVis: 7 graphics on avalanche fatalities

Decades of data show where and how people die due to sliding snow

Avalanches terrify me. The risk of getting caught in one is a major reason why I’ve done very little backcountry skiing, despite an aching desire to get out there more.

Eight years ago, I got my Level 1 avalanche certification, but that excellent three-day course at the Colorado Mountain School in Estes Park convinced me that I still had no business being in serious avalanche terrain without a competent person or people guiding me.

Unfortunately, a little knowledge can be dangerous when it comes to avalanche risk: people think taking a course, reading a book, and/or getting rescue gear means they’re good to go, but some folks pay for that misplaced confidence with their lives.

Sadly, plenty of experienced alpinists also die during avalanches, as do clueless novices who don’t bring along the bare essentials.

I’m definitely no expert on avalanches, but lately I’ve been learning more about them due to my fascination with snow and my desire to spend more time beyond the boundaries of ski resorts. In my reading, I’ve come across some interesting data on avalanche fatalities that I visualize below.

I relied on two data sources to create these graphics: the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) and Bruce Tremper’s excellent and accessible Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain.

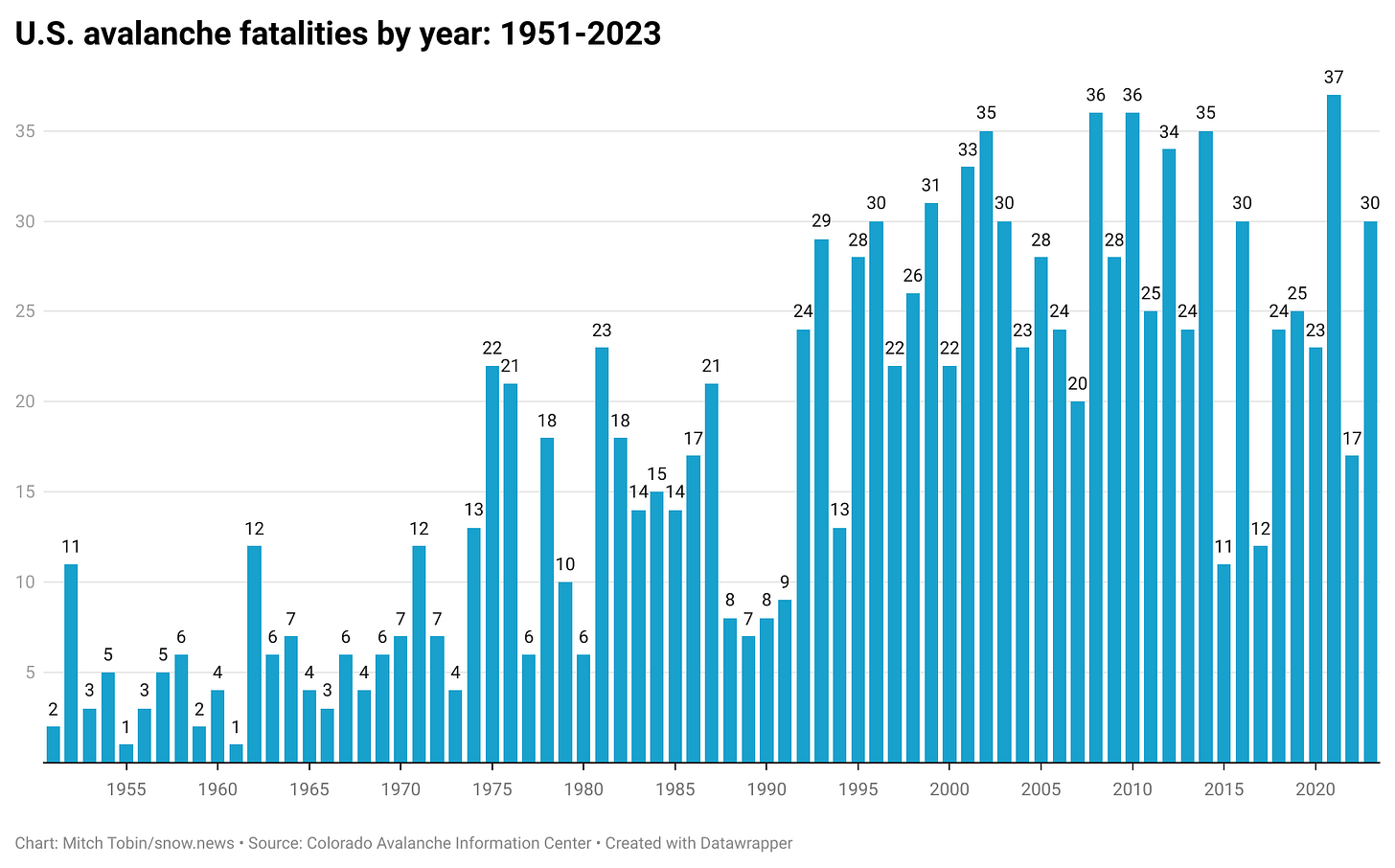

Charting decades of avalanche deaths

The CAIC, situated in America’s avalanche epicenter, maintains a database on U.S. fatalities back to 1951. The chart below plots the number of annual deaths, which has maxed out around three dozen in recent years.

The graphic above shows an overall trend of rising fatalities, but the U.S. population more than doubled from 1951 to 2023, so I took that into account below. Ideally, we’d somehow come up with the number of people recreating, working, and traveling in avalanche country every year to factor in the exposure to the risks, but good luck with that. Still, it’s clear that activities such as backcountry skiing and snowmobiling are a lot more popular than they were decades ago.

A cruder approximation entails dividing the fatalities by the overall population, shown in the lower right panel. There’s a slight upward trend, but the data is as spiky as a sawtooth range. Avalanches are rare enough that I expressed this number per 100 million Americans.

Colorado has the most fatalities

The map below shows that Colorado’s 323 deaths lead the nation by a longshot and are nearly double the figure for second-ranking Alaska.

It’s no mystery why Colorado has so many avalanche deaths: tons of people recreate in our legendary backcountry, and the state’s relatively thin and dry continental snowpack is notoriously sketchy. “Since 1950 avalanches have killed more people in Colorado than any other natural hazard,” according to the Colorado Geological Survey.

You might be wondering about that fatality in North Dakota, which isn’t known for its avalanche terrain. That’s the 2008 death of someone who was shoveling the roof of a warehouse in Fargo.

Deaths peak in January and February

The chart below shows how the fatalities are spread throughout the year. October is the only month with no recorded deaths, though there are only a handful in July, August, and September.

Who dies in avalanches?

People recreating in the backcountry dominate the fatalities, as shown in the chart below. This is an interesting aspect of avalanches: most people are having a good time when disaster strikes. There are analogous hazards out there, such as flash floods in slot canyons, mishaps while climbing, riptides at the beach, and getting zapped by lightning while playing golf, but I was struck by the prevalence of recreational activities in the data on avalanche fatalities.

People at work also die in avalanches, including ski patrollers, highway personnel, and mountain guides, not to mention the rescuers tasked with the unenviable task of responding to the initial tragedy.

Based on CAIC data, Tremper’s book notes that 90% of avalanche fatalities are male.

What types of conditions cause deaths?

Like many natural hazards, avalanches are rated by a danger scale. The North American system uses five categories: low, moderate, considerable, high, and extreme (see this page for details).

The chart below, based on data from Tremper’s book, compares deaths in the United States, Canada, and Switzerland according to the five-category system. Very few people perish when the danger is low because the risk is minimal, and not many people die when the danger is rated extreme because there are only so many people who are foolish enough to poke the dragon. The highest number of deaths occurs when the rating is in the middle “considerable” category.

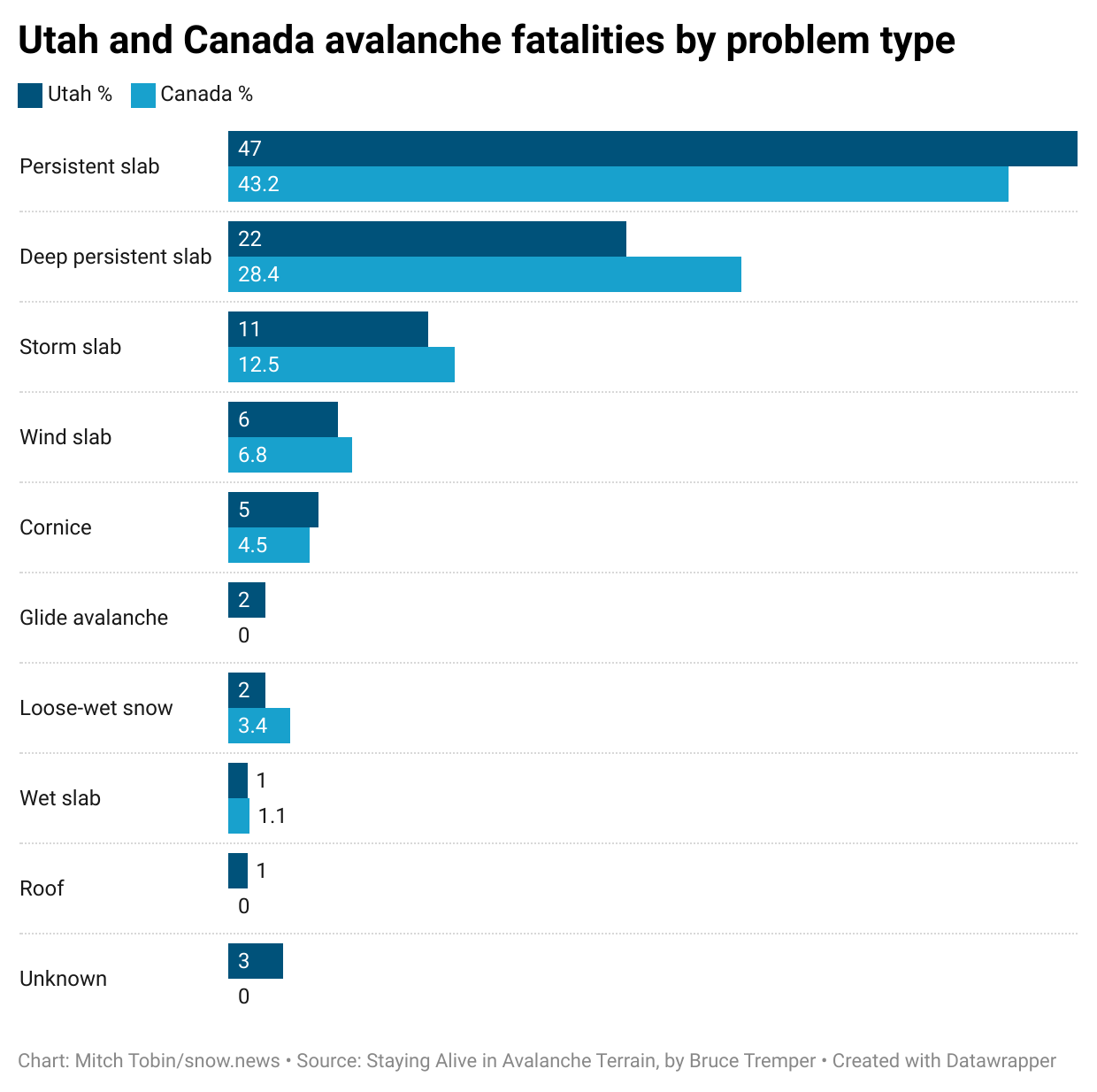

Avalanches come in a variety of forms, which are often referred to as “problems.” The graphic below, based on data in Tremper’s book for Utah and Canada, shows which types of avalanches cause the most fatalities.

What screams out from this chart is that avalanche deaths are about slabs of snow hurtling down the mountain, especially those in the “persistent” categories.

Without getting into the complex, fascinating world of avalanche science, let me briefly lay out a persistent slab avalanche: a weak layer of snow gets buried and lies in wait, then it’s loaded by a thicker, more coherent slab of snow that is eventually triggered, creating an avalanche that may be unsurvivable even if victims have airbags and rescue gear. Tremper likens those deep, weak layers to “monsters in the basement.”

A reasonable person might wonder why it’s worth taking such risks—why not just stick to resorts where patrollers control avalanches with explosives and other measures? That’s been compelling logic for me (though 51 inbounds riders have perished due to avalanches since 1951). Plus, I’m awfully slow when skinning uphill, so the unappealing ratio of slog to shred has also kept my ski touring aspirations at bay.

But it’s undeniable that backcountry skiing opens up a world of raw, immeasurable beauty that’s not available in ski resorts, which are increasingly like theme parks, sometimes with lines just as long.

I’ve only had a few tastes of backcountry skiing, mostly on Colorado’s Front Range, but I’ve also experienced heli-skiing and quasi-backcountry conditions at Silverton Mountain ski area, where you’re required to bring rescue gear, though patrollers do some avalanche control.

Those tastes have whet my appetite. All that untracked powder in the backcountry beckons. But like most things in life, the rewards come along with risks.

Hi Mitch, would it be possible to re-use this image of the snow instructor on a website (with you fully credited!)? It's really beautiful. Thanks.

Wow so interesting! Awesome page!!!