10 snow stories on my radar

Forecasting, eating, making, and mapping snow, plus a snowpack update

Here’s a quick rundown of 10 snow-related stories I’ve been following, including an update on the West’s meager snowpack at the end.

🤖 1) AI informs snowfall forecasts

The liquid content of snow varies from storm to storm and place to place. That’s a major reason why predicting snowfall totals is so challenging—especially in complex, mountainous environments. Sometimes the snow is light and fluffy; other times it’s dense and laden with moisture.

A new study in Weather and Forecasting concludes that machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence, can provide crucial insights into the snow-to-liquid ratio, a key variable for predicting snow accumulation and its water content.

“If you don’t have a good snow-to-liquid ratio, your snowfall forecasts are not going to be as good,” said lead author Peter Veals, a University of Utah research assistant professor of atmospheric sciences, in a university press release.

The researchers used high-quality, manually collected snow data from 14 mountain sites in the West, along with local atmospheric conditions, to train machine learning models. Those algorithms did a far better job at predicting snow-to-liquid ratios than existing methods.

“In simple terms, the new approach will enhance the reliability of snowfall forecasts, which would be helpful for the West’s water resource managers, highway officials, weather forecasters and avalanche professionals who depend on knowing how much water the snow holds,” according to the press release.

🚫 2) Is it OK to eat snow?

Everyone knows not to eat snow that’s yellow or dirty. But Colorado State University snow hydrologist Steven Fassnacht says there can be plenty of other unappetizing things lurking in snow that you should avoid putting in your mouth.

In an interesting interview with CSU’s The Audit podcast, Fassnacht notes that snow can contain dust, forever chemicals, heavy metals, microplastics, and other contaminants. “The big ones that we see around here are nitrogen and sulfur-based,” he said. “They come out of the tailpipe, out of the smokestack, et cetera. So, if you’re downwind from a major industrial source of these, then the likelihood that you have these in the snowpack is a lot higher.”

Because a snowflake has more surface area than a raindrop, it can pick up more chemicals in the atmosphere. And around the planet, scientists are finding that tiny pieces of plastic are everywhere.

“Think about going out in the snow. You’ve got plastic ski boots on and plastic skis and poles, and your jacket and all your equipment, that’s all plastic,” Fassnacht said. “Any breakdown of that—which will happen over time—is going to put microplastics onto the snowpack.”

Other sources note that snow can contain microbes and pesticides. The Cleveland Clinic says, “If the flakes are undisturbed, pristine white and come from the top layer, it’s typically safe to indulge in a scoop.”

Fassnacht, who said he sometimes eats snow himself, offered this advice: “Most of the time you’re probably OK, but you want to really be aware of where you are eating this snow.”

⛷️ 3) Sensitivity of ski resorts to climate change

An analysis of 41 ski areas in Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California finds that “while many resorts indeed face substantial declines in ski-season snow depth, many of those in Idaho and a few at high elevation are likely to be minimally affected.”

The preprint, which is under review at The Cryosphere, identifies several mitigating factors that could offset warming in some locations, including increased winter precipitation, colder conditions at high altitudes, and historically heavy snowfall. Winter snow also tends to be less sensitive to warming than spring snow, and many resorts span wide elevation ranges that provide a natural buffer.

“Although a warming climate clearly poses an existential risk to winter sports, our analysis shows that this broad-brush picture misses some important exceptions,” the researchers write. “In the western US, the wide variety of climates under which ski resorts operate means that they have very different exposures to climate change.”

🏂 4) How snowmaking works

As ski areas grapple with climate change, they’re increasingly turning to snowmaking to make up for what Mother Nature fails to supply.

Two new stories examine the art and science of making artificial snow—and how much water and energy are needed in the process:

“Climate change makes snowmaking a necessity, not a backup, for the West’s ski resorts,” Caroline Llanes, Rocky Mountain Community Radio, December 11, 2025 (this story was produced in partnership with The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative at the University of Colorado Boulder, which I co-direct).

“How Southern California resorts bring snow to the slopes during warm winters,” Laylan Connelly, Orange County Register, December 12, 2025.

Llanes reports from Colorado’s Keystone Resort, where the snowmaking guns have a built-in weather system that monitors temperature and relative humidity to optimize their performance. Citing Fassnacht, mentioned above, Llanes writes that “about 80% of the water used in snowmaking goes back into the watershed it came from,” but the amount of water used for snowmaking may rise if conditions get drier. The story also notes that snowmaking can be contentious:

“Telluride Resort is currently in a dispute with the town of Mountain Village over its water use, and a federal court recently dismissed a lawsuit from Purgatory, a resort near Durango, over accessing decades-old groundwater rights on Forest Service land.”

In Southern California, Connelly reports that the ski resorts situated between the desert and the Pacific Ocean have been investing millions of dollars in snowmaking and adopting more energy-efficient technologies that reduce diesel consumption. Big Bear Mountain Resort’s three ski areas “have 700 hydrants, 330 snow guns and 40 fans, with the ability to transform up to 6,000 gallons of water into snow every minute,” according to the story. “It’s a serious science,” Snow Summit’s Chris Winslow told Connelly. “It’s hard to make snow in Southern California. We literally would not be able to ski or ride in Southern California without snowmaking.”

As I noted in a prior post, a 2024 study found that snowmaking expenses run from $1,257 per acre in the Pacific Northwest to $2,673 per acre in the Northeast. That paper concluded that U.S. ski areas lost more than $5 billion from 2000 to 2019 due to fewer visits and higher snowmaking costs associated with climate change.

📊 5) Graphics show how U.S. snowfall is changing

As longtime readers know, I love data visualizations, so when I saw The Washington Post publish a series of maps and charts on snowfall trends and recent projections, it immediately caught my eye.

I’m a firm believer in copyright protections, so I won’t republish WaPo’s visuals here, but I’d encourage you to check out the excellent November 16 package by Ben Noll and Daniel Wolfe.

“A new analysis by The Washington Post found that swaths of the Plains, Midwest and East Coast have received much less snow than average over the past five winters — a trend that may continue this season, unless the polar vortex makes an early winter visit,” Noll and Wolfe write. “Around 70 percent of states in the contiguous U.S. have seen declining snowfall in recent winters, although parts of the West and some of the South have experienced more snow.”

🌡️ 6) Sharp drop in a Rocky Mountain pika population

The American pika (Ochotona princeps), a small, squeaky, rabbit-like mammal, is considered an indicator species for climate change impacts on alpine ecosystems. A new study in Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research finds that warming temperatures and changing snow conditions are stressing a population of pikas, which are commonly seen scurrying on talus slopes in the Rocky Mountains.

Pikas can only survive in a narrow temperature range. “Across most of its range, the pika requires snow cover for insulation during the cold season, as well as warm-season access to cool subsurface spaces—like those found in rock glaciers—where it can shed heat passively,” according to the paper.

The study is based on long-running survey data from the Niwot Ridge Long Term Ecological Research site, about 10 miles south of Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. “The researchers discovered that the ‘recruitment’ of juveniles to this site seems to have plummeted since the 1980s,” according to a University of Colorado Boulder press release. “In other words, these populations are becoming dominated by older adults, with fewer juvenile pikas being born, or migrating in, to take their place.”

“Pikas don’t pant like a dog. They don’t sweat,” Chris Ray, lead author of the study and a research associate at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, said in the release. “The only way they can release their metabolic heat is to get into a nice, cool space and just let it dissipate.”

The Colorado Sun’s Michael Booth wrote that the study offers “more proof that the ravages of warming from climate change threaten the pika’s very existence in the Rocky Mountains.”

🏔️ 7) Snow droughts and deluges affect Yosemite visitation

Snow droughts and snow deluges are the yin and yang of winter extremes.

At California’s Yosemite National Park, the lack or surplus of snow can shape tourism and recreation, according to a recent study in Scientific Reports. The researchers also analyzed how the park’s reservation system influences visitation.

“Changes in snow extremes can have important but as yet underexplored impacts on the 1.2-trillion dollar outdoor recreation industry, impacting essential ecosystem services,” the researchers write. “Climate change extremes and associated hazards limit and enable access in different ways: snowpack from extreme wet years can prolong road closures at higher elevations, while extreme snow drought enables early season access.”

The study found that “annual use levels are influenced more by managed access than by climate extremes.” The authors conclude that their findings “suggest that appropriately managed reservation systems are an essential tool for managing recreation resources in a changing climate.”

If you’d like to learn more about snow droughts and deluges, check out my conversations with scientists who study them:

💧 8) Tibetan Plateau snow droughts impact water supply for 1.5 billion people

Beyond affecting outdoor recreation, snow droughts can also pose a profound threat to the people who rely on snowmelt for their water supply.

A recent paper analyzes the cascading effects of snow droughts across the Tibetan Plateau, the headwaters for 10 major rivers—including the Yangtze, Indus, and Ganges—that provide water to around 1.5 billion people downstream.

“Escalating impacts of snow droughts have critically threatened hydrological stability and socioeconomic resilience on the Tibetan Plateau, Asia’s alpine water tower,” the researchers write in Communications Earth & Environment.

Analyzing data from 1979 to 2022, the scientists found “significant increases in severity” for both “warm” snow droughts (caused by a shift from snow to rain and accelerated melting) and “dry” snow droughts (caused by a lack of cold-season precipitation).

The study concluded that snow droughts are not only imperiling the water supply—they’re also transforming the region’s hydrologic cycle and worsening other climate extremes, such as hot/dry spells and hot/wet periods. Snow droughts can influence the Asian monsoon, alter soil moisture levels, and reduce the land surface's reflectivity (albedo).

The Tibetan Plateau is so critical to the planet’s cryosphere and climate that it’s often called the “Third Pole.” Temperatures there are warming at roughly twice the global average rate.

❄️ 9) The State of the Cryosphere report

It’s not an uplifting read, but the State of the Cryosphere 2025 report offers a solid synthesis of scientific research on Earth’s frozen places.

“Current unambitious climate commitments, leading the world to well over 2°C of warming, spell disaster for billions of people from global ice loss, but that damage can still be prevented,” according to the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, which produced the report. “The European Alps, Scandinavia, North American Rockies and Iceland would lose at least half their ice at or below sustained global temperatures of 1°C, and nearly all ice at 2°C.”

Citing a 2025 study, the report also warns that “snowpack in the Western United States, a critical water source for 100 million people, is set to lose 34% of its seasonal volume by 2100.”

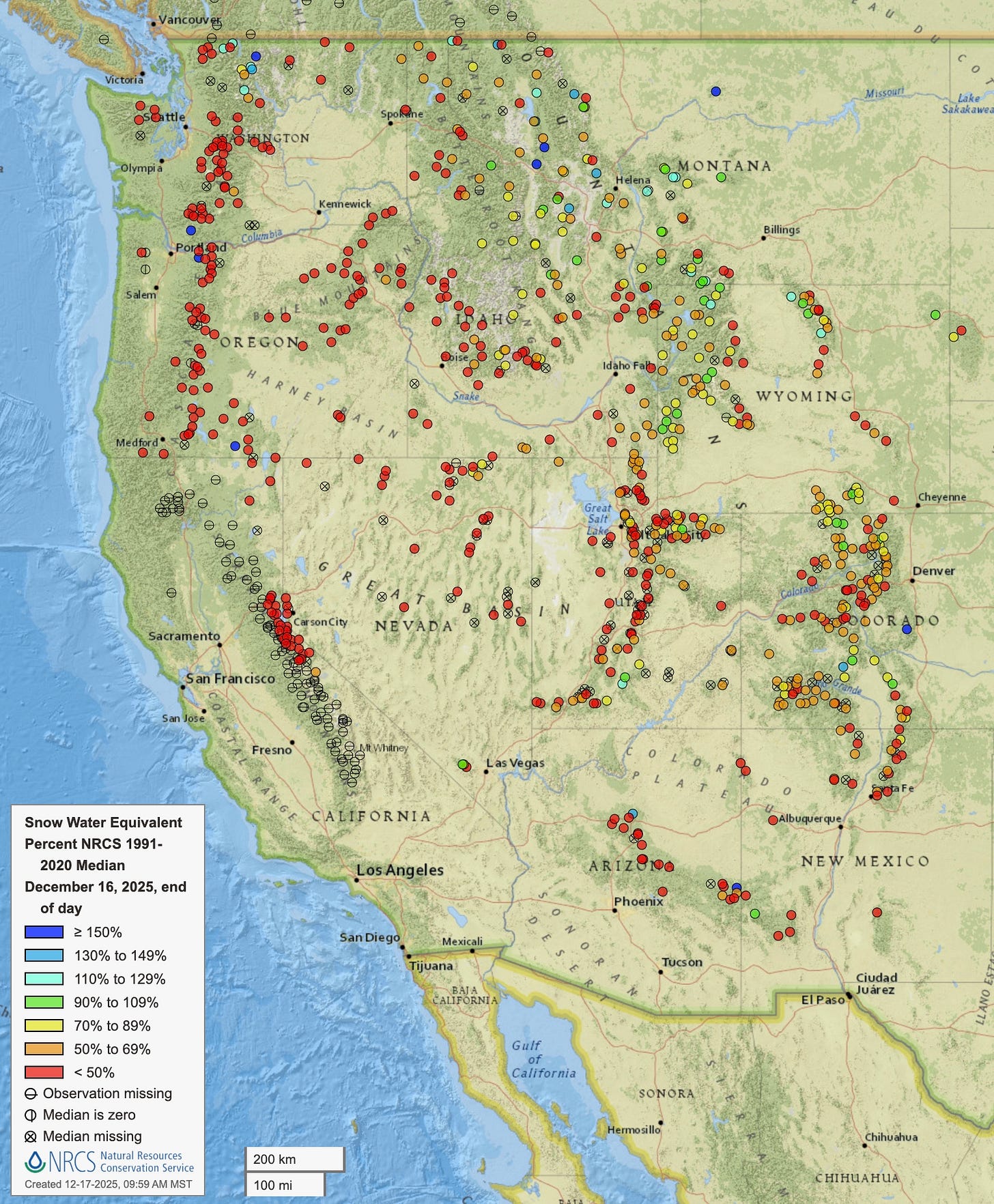

😱 10) Snowpack update

In my previous post, I wrote about the grim status of the West’s skimpy snowpack. I’m sorry to report that the situation remains bleak across most of the region.

The December 16 map below shows the snow water equivalent readings at individual monitoring sites. All those red dots mean this measure of the snowpack’s water content is below 50% of the median (1991–2020); orange dots indicate 50% to 69%.

In a December 11 update, the federal National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) reported that December 7 snow cover across the West was the lowest for that date in the satellite record since 2001.

“Nearly every major river basin in the West experienced a November among the top 5 warmest on record,” NIDIS said, adding that “much warmer-than-normal temperatures caused precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow across many basins, leading to snow drought despite wetter-than-normal conditions across most of the West.”

⏸️ Programming note: With winter break approaching, I’ll be taking some time off and shifting from writing about snow to playing in it on a road trip to Colorado ski resorts. I’ll resume publishing after the new year.

In the meantime, you can keep up with my alpine exploits on the snow.news Instagram, Facebook, and Threads accounts, where I’ve started sharing more of my photos of snow, skiing, and snowboarding.

Happy Holidays!

Love this post format! Hope 2026 brings more snow!