How climate change is harming the U.S. ski industry

Plus pretty photos of Telluride, from the slopes and from above.

A fascinating new study imagines what the U.S. ski industry would have been like without climate change and projects the steep economic damages that ski areas will suffer due to further warming.

From 2000 to 2019, ski areas lost more than $5 billion due to fewer visits and higher snowmaking costs, according to the paper.

“We are probably past the era of peak ski seasons,” the study concludes, “for even with advanced snowmaking, average ski seasons in all regional markets are projected to get shorter in the decades ahead under all emission futures.”

Compared to the 1960-1979 period, when many U.S. resorts started up, ski seasons from 2000 to 2019 shortened between 5.5 and 7.1 days, according to the February paper in Current Issues in Tourism.

Looking ahead to the 2050s, the study projects the ski season will be cut by 14 to 33 days under a low greenhouse gas emissions scenario and 27 to 62 days under a high-emissions pathway, with annual losses ranging from $657 million to $1.35 billion.

As any skier or snowboarder will tell you, these glorious activities can drain your bank account, yet all that spending boosts the U.S. gross domestic product by more than $29 billion and supports over 530,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

The paper, “How climate change is damaging the US ski industry,” was authored by Daniel Scott of the Department of Geography and Environmental Management at the University of Waterloo in Canada and Robert Steiger of the Department of Public Finance at the University of Innsbruck in Austria.

The authors write that one of the motivations for looking back in time at how climate change has already harmed the ski industry is to quantify the damages, which could inform litigation filed by communities against the fossil fuel industry.

In 2018, Colorado’s Boulder County, San Miguel County (home to Telluride), and the City of Boulder sued ExxonMobil and Suncor for their “intentional, reckless and negligent conduct” connected to past and future climate change; the case is ongoing.

“Similar climate litigation by ski tourism destinations or ski companies could follow this precedent and would require evidence of the current and future financial damages caused by climate change at the industry and plaintiff scale (destination community or individual business),” according to the study.

The researchers examined 226 downhill ski areas in the four regions that accounted for 96% of skier visits in the 2022-2023 season. To tally the economic harm done by warming, “the analysis investigates how long ski seasons would be and what snowmaking would be needed if the climate in the 1960s and 1970s had persisted.”

The shorter operating seasons have deprived ski areas of many revenue sources: the expensive lift tickets, the overpriced food/beverages, and all that money spent on rentals, lessons, lodging, shopping, and more. The average winter revenue per skier visit ranged from about $65 for ski areas in the Pacific Northwest to around $113 in the Pacific Southwest and Rockies.

The study also calculated the added expenses of snowmaking, which can lengthen the season but isn’t cheap. To make fake snow, resorts must spend money on the equipment and pay for the labor to run the guns while also racking up the economic/environmental costs of using water and energy. Snowmaking expenses run from $1,257 per acre in the Pacific Northwest to $2,673 per acre in the Northeast, according to the study.

The paper’s estimates for economic losses are conservative because they only account for lost visits and higher costs for snowmaking for resorts. The study doesn’t measure the ripple effect of shorter seasons on surrounding businesses and communities—just think of all those ski country hotels, bars, restaurants, retail stores, gas stations, and other places where tourists hemorrhage money.

Like any business in a capitalist economy, ski resorts and their parent companies, such as Vail Resorts (NYSE: MTN, $8.6 billion market cap) have rolled with the punches and increasingly turned to snowmaking as a way to adapt to climate change.

“The massive investment in snowmaking enabled US regional ski markets to increase the average ski season length from the 1980s to 1990s (except the Midwest) and again from the 1990s to 2000s, even as temperatures increased and an average length of annual snow cover began to decline,” the study said.

But if it gets warm enough, even snowmaking is impractical, so the paper concludes that “the adaptive capacity of snowmaking is no longer able to completely offset ongoing climate changes.”

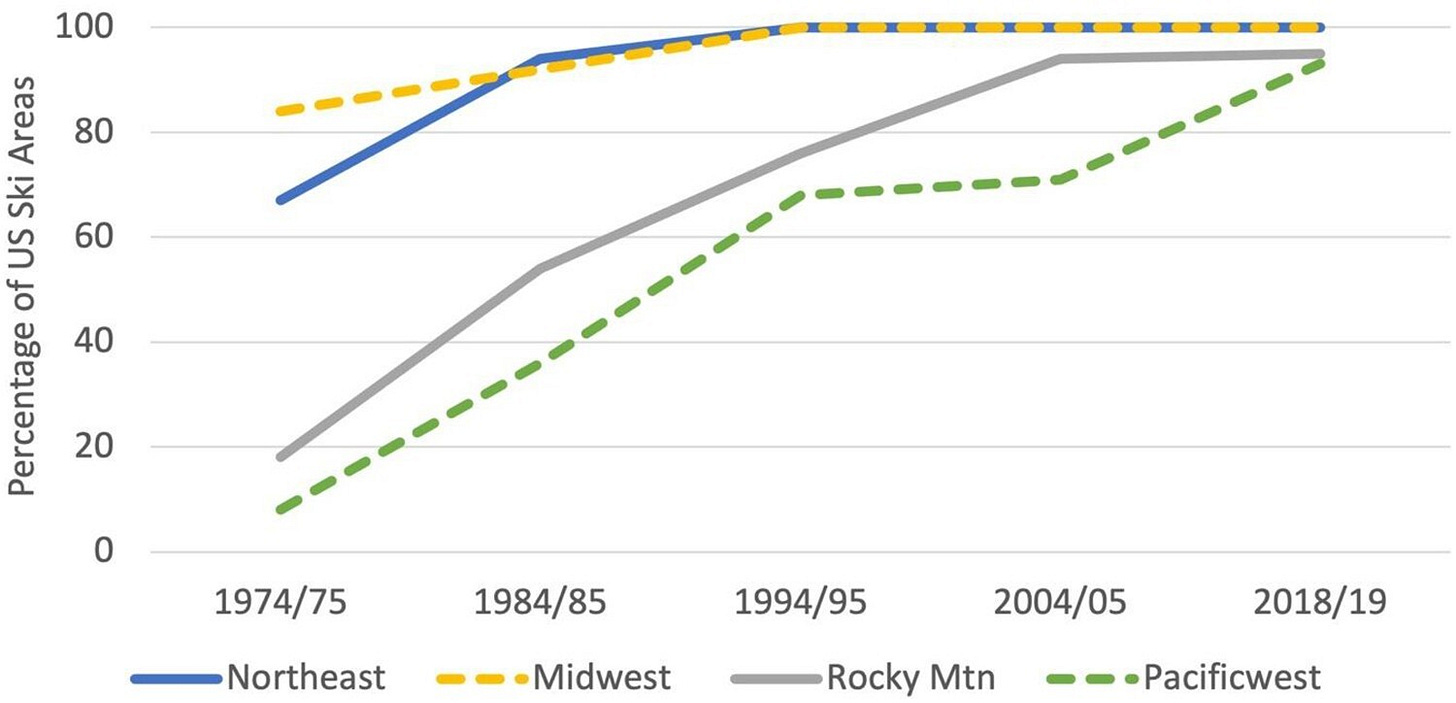

The graphic below from the paper shows the share of ski areas using snowmaking over time. In the Rockies and Pacific regions, fewer than one in five resorts made snow in 1974/1975, but nowadays nearly all do. Even back in the 1970s, most resorts in the Northeast and Midwest regions were at least blowing some artificial snow; today, virtually all do it.

“Regions of the US where snowmaking is most likely to be maladaptive because of higher water insecurity and carbon-intense electricity grids, include New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming,” the authors write. “Securing access to water requirements for future snowmaking may prove increasingly difficult in many western States where water insecurity is projected to increase . . .”

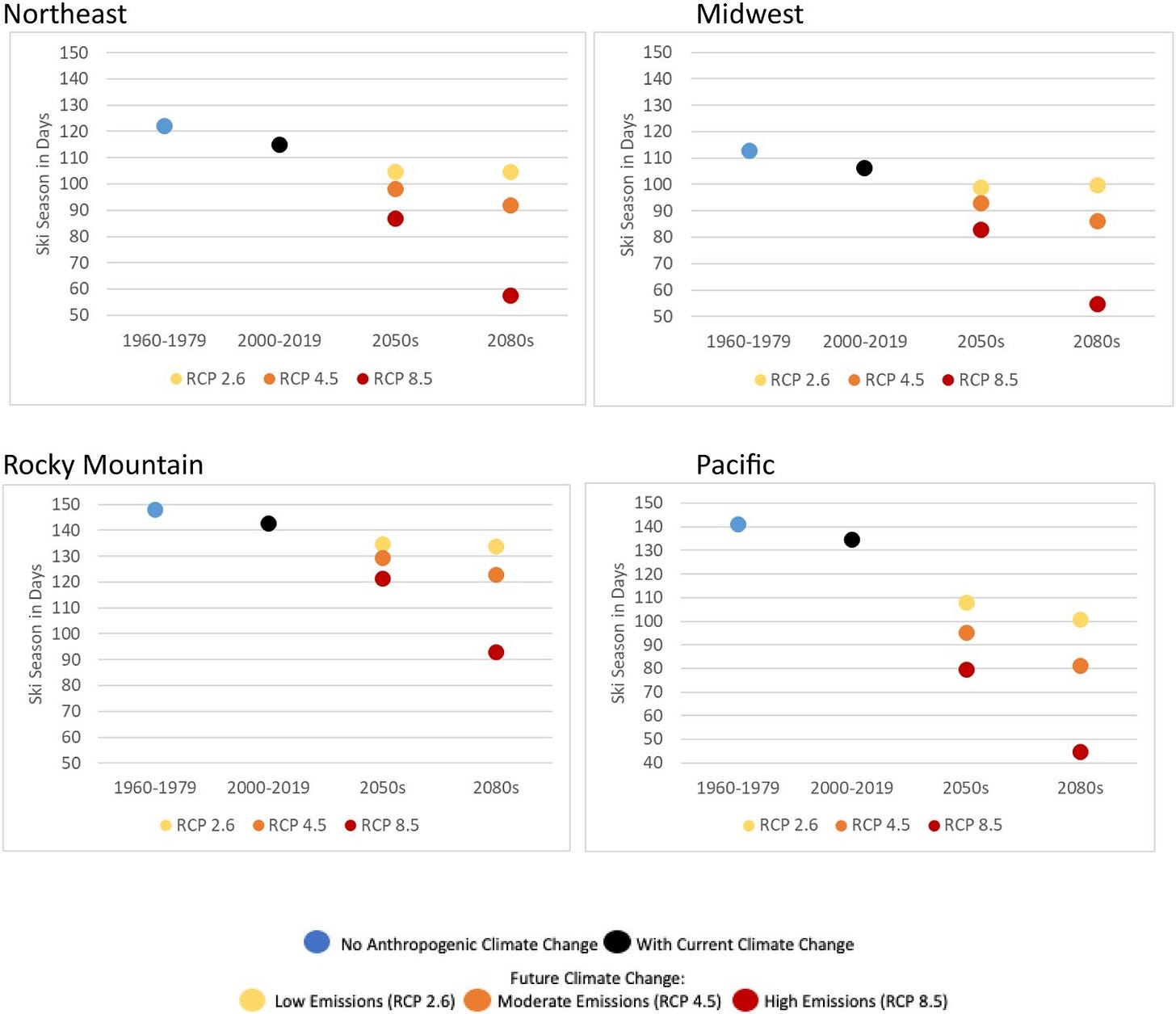

The chart below shows historic changes in the length of the ski season and projections for the future, again broken down by region. The blue dots show the season length in the 1960-1979 period and the black dots depict the 2000-2019 period. In every region, the season has gotten slightly shorter, but looking ahead to the 2050s and 2080s, much sharper decreases are expected, especially if emissions rise rapidly. The yellow, orange, and red dots correspond to low-, medium-, and high-emissions scenarios.

In the Pacific region, the ski season would be 33 days shorter by the 2050s under a low-emissions scenario and 62 days shorter under a high-emissions scenario. By the 2080s, a high-emissions scenario—which some researchers think is way too pessimistic—would shorten the ski season by 55 days in the Rockies and 97 days in the Pacific region.

Telluride photos: on the slopes and from above

The competition is stiff, but Telluride may be Colorado’s prettiest ski area. Aspen/Snowmass, Crested Butte, and Silverton are also high on my list. Clearly, further research is needed.

Below is a gallery of photos from a recent day trip to Telluride (click images to enlarge).

Last year, I was able to photograph the same area from a few thousand feet above in a single-propellor plane piloted by a volunteer with LightHawk, a nonprofit flying service.

As part of my work at The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative at the University of Colorado Boulder, I’ve had the good fortune to take some LightHawk flights over Colorado to photograph key water-related locations for our free multimedia library, which I’d encourage you to explore if you ever need imagery related to water/snow in the Southwest.

In May, I took a gorgeous flight around the San Juan Mountains to photograph last season’s hefty snowpack. We left from Durango and did a loop that took us over the Dolores River, Telluride, Silverton, and the Animas River. Below are some of the photos I snapped on the flight. See this page for the full set, which also includes imagery of the snowpack in the La Plata Range.

Thanks for summarizing the Scott & Steiger paper, Mitch. There's some staggering implications involved in their modeling.