The Winter Olympics vs. climate change

Plus: an update on the snowpack (bad) and photos from a rare powder day (good)

Snow and ice underlie the sports of the Winter Olympics, so with the competition about to begin in Italy, there has been a flurry of recent stories about how climate change is affecting the Milan Cortina Games and the event’s future.

With enough refrigeration—and associated greenhouse gas emissions—indoor sports such as hockey and skating could theoretically take place anywhere in the world, during any season. NHL games, for example, are already played in warm climates, including South Florida, Tampa Bay, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and, until recently, the Phoenix area.

But for outdoor events, such as skiing and snowboarding, weather and climate remain pivotal—and increasingly problematic.

For decades, the Olympics have featured not only fierce struggles among athletes but also an increasingly pitched battle between organizers and Mother Nature—one that has required escalating measures to ensure there’s enough frozen water to support the Games.

“The tenability and success of future Winter Games will depend on whether the international community achieves the temperature goals of the Paris Climate Agreement or remains on track for global warming near 3°C,” according to a January 20 study in Current Issues in Tourism, which I summarize below along with other peer-reviewed research on the Winter Olympics.

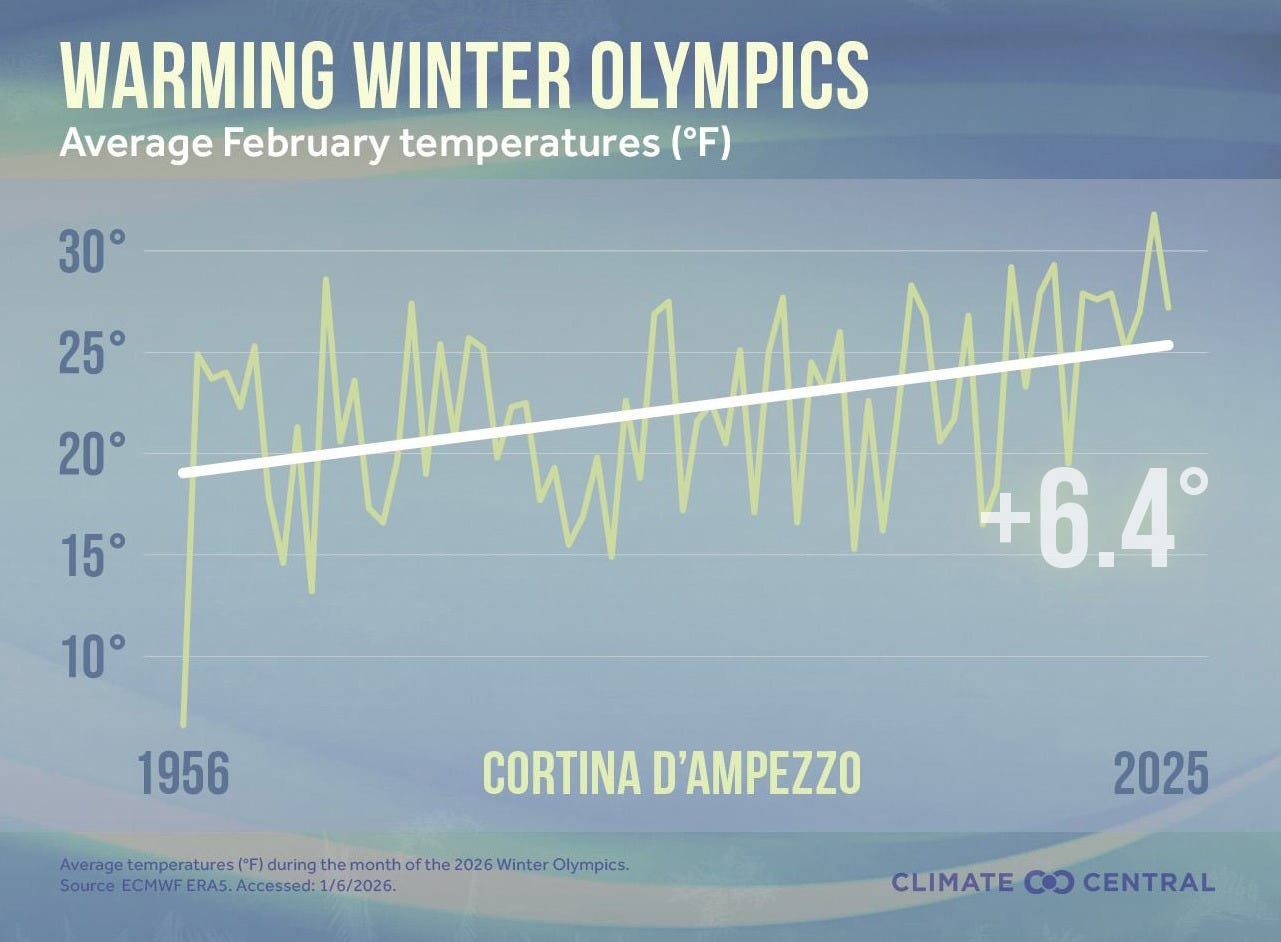

The Games were first held in Cortina d’Ampezzo in 1956, but that location in the Italian Alps now experiences 41 fewer freezing days per year (a 19% decline), according to Climate Central, a nonprofit that describes itself as “policy-neutral.” As shown in the chart below, average February temperatures in Cortina have warmed 6.4°F over the past 70 years.

Snowfall in the Alps has been decreasing, as The New York Times reports:

Across the entire southern Alpine region, the average depth of winter snowfall has declined by more than 25 percent since 1980, according to a 2024 study of a century of snowfall records published in the International Journal of Climatology.

Once again, this year’s competition will make heavy use of artificial snow. In the 2022 Beijing Games, 100% of the snow was machine-made, according to a 2022 story in Time. The figure was about 80% in the 2014 Sochi Games in Russia and as high as 98% for the 2018 Pyeongchang Games in South Korea.

Although some athletes have complained about the manufactured snow, others actually prefer the icy, consistent surface in their sports (more on this below). For details on snowmaking at this year’s games, see this Associated Press story about the Italian expert who is responsible for supplying several courses with what he calls “technical snow.” Two reservoirs—each holding tens of millions of gallons of water—were built to support snowmaking at the Milan Cortina Games.

A quick guide to research on the Winter Olympics and climate change

In addition to journalism, there’s a growing body of peer-reviewed research examining how climate change could affect the Olympic Winter Games and the athletes who compete in them.

Below are brief, plain-language summaries of five studies published since 2014 in Current Issues in Tourism. All were co-authored by Daniel Scott, a professor of geography and environmental management at the University of Waterloo in Canada and one of the leading researchers studying climate change impacts on the Winter Olympics.

“When we say climate-reliable, that means, ‘Can you deliver the high-quality snow for competition 90% of the time,’” Scott said in a story by Bob Henson at Yale Climate Connections. “We’re never saying that’s foolproof … We’re using the best available scenarios, but that’s not to say climate change couldn’t throw yet another curve ball at future hosts.”

The future of the Olympic Winter Games in an era of climate change. Scott et al. (2014).

This seminal paper projected how climate change could affect the ability of past Winter Olympic host cities to provide naturally cold, snowy conditions suitable for outdoor events. The researchers used two key indicators: the probability of a minimum temperature below 0°C (32°F) and snow depths exceeding 30 centimeters (11.8 inches).

During the 1980-2010 period, all 19 former hosts had suitable climates. By the 2050s, however, the number of reliable locations among former hosts fell to 11 in a low-emissions scenario and 10 in a high-emissions pathway. In the 2080s, only six former hosts would remain “climatically suitable” in the high-emissions scenario.

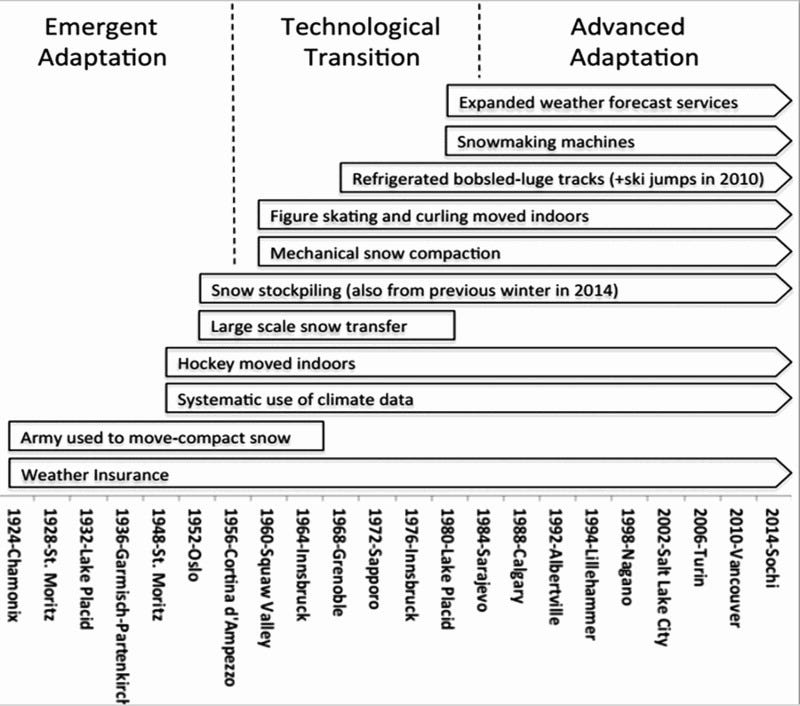

Weather risk management at the Olympic Winter Games. Rutty et al. (2014).

Researchers examined how weather affected the Games from 1924 to 2010—and how organizers have responded to the changing conditions. “Analysis reveals that while weather-induced impacts have always been a part of the Games, these impacts would be far greater if not for technical climatic adaptations,” the authors write.

The average daytime temperature at Winter Olympic host sites increased from 0.4°C (32.7°F) at the Games held between the 1920s and 1950s to 7.8°C (46.0°F) at the 21st-century competitions. The timeline below shows how the Winter Olympics has increasingly relied on adaptations—from snow compaction and indoor venues to snowmaking and refrigerated tracks—to manage weather risks as temperatures have risen.

Climate change and the future of the Olympic Winter Games: athlete and coach perspectives. Scott et al. (2022).

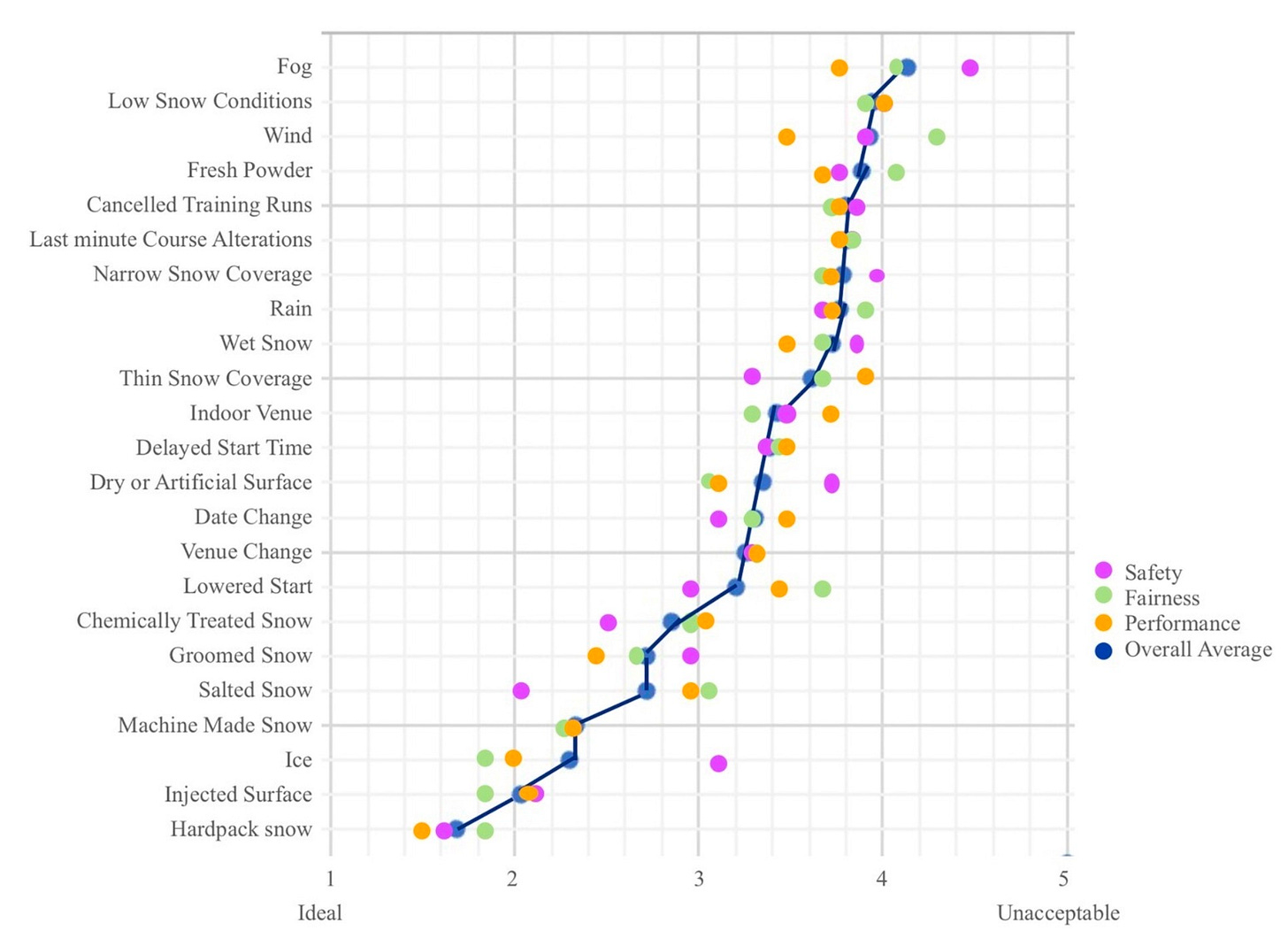

It’s one thing to watch the Olympics, but what do the athletes themselves think of how conditions are changing as the planet warms? This study surveyed 339 elite athletes and coaches from 20 countries to define “fair and safe conditions for snow sports competitions.”

The researchers concluded that the likelihood of unfair and unsafe conditions has risen over the past half-century across 21 Winter Olympic venues. “The probability of unfair-unsafe conditions increases under all future climate change scenarios,” the researchers write. “Athletes expressed trepidation over the future of their sport and the need for the sporting world to be a powerful force to inspire and accelerate climate action.”

The chart below shows how the respondents rated both weather conditions and organizers’ responses on a spectrum from ideal to unacceptable across three dimensions: safety, fairness, and performance. At first glance, some of the results may seem paradoxical. “Fresh powder” is rated as one of the most unacceptable features, while “hardpack snow” and “ice” rank among the most ideal conditions—precisely the opposite of what most recreational skiers and snowboarders prefer. But in elite competitions, speed, consistency, and predictability—not fun, soft, and forgiving snow—are what athletes tend to prioritize. Ice illustrates the tradeoffs: despite a moderate safety rating, it ranks highly for fairness and performance.

Climate change and the climate reliability of hosts in the second century of the Winter Olympic Games. Steiger and Scott (2024).

This study analyzed the climate reliability of 93 potential host locations for snow sports at the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Under a mid-range scenario for greenhouse gas emissions, the authors concluded that only 52 locations would be reliable choices for the Olympics in the 2050s, falling to 46 in the 2080s.

The outlook is even more constrained for the Paralympic Winter Games, which take place later in the season. Under the same emissions pathway, the number of climate-reliable Paralympic host locations drops to 22 in the 2050s and 16 in the 2080s.

The study notes that “a low emission future poses a much lower risk to the number of potential host locations that can be considered climatically reliable.” On a positive note, among the locations projected to remain viable under the mid-range climate scenario, all major global regions that have previously hosted the Olympics—North America, Europe (Alps, Scandinavia, Eastern Europe), and Asia—retain multiple potential hosts in the decades ahead.

Advancing climate change resilience of the Winter Olympic-Paralympic Games. Scott et al. (2026).

Published on January 20, this new paper identifies “a range of strategies to advance the climate resilience of the Winter Olympics-Paralympics.” The options vary from host-city selection and scheduling changes to operational measures, such as stockpiling snow from the previous winter and relocating competitions to higher elevations.

The study examines the challenges posed by the current “one bid, one city” policy, which requires a host to stage both the Olympics (February) and the Paralympics (March). Because the climate generally is more problematic in March, “this has the effect of significantly reducing the number of climate reliable potential hosts.” Holding both games simultaneously in February is “a contentious solution with strong arguments for and against it,” the authors write, adding:

A merger supports full equality of athletes, potentially increasing visibility and sponsorship opportunities for Paralympic sports. There are also potential logistical and financial efficiencies that could attract more hosts. Critics of a unified games voice concerns that Paralympic events might be overshadowed by Olympic events.

A unified event would be more complex, but the competition could be extended from the current 16 days to 20 or 24 to solve scheduling challenges, the paper notes. Other options include holding the Paralympics in February at a different location, or maintaining the “one bid, one city” approach while shifting the events earlier by two to three weeks, but those strategies have their own tradeoffs.

The 2026 paper also tackles the sustainability of snowmaking, which has been used at every Winter Olympics since the 1980 Games in Lake Placid. While the authors note that “reliance on snowmaking will increase in the decades ahead,” the practice has drawn criticism for its environmental footprint.

“There has been a surprising lack of research evaluating the water, energy, and related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions used in snowmaking, but state-of-the-art snowmaking and grooming systems have been shown to reduce water (20–40%) and energy (up to 70%) requirements significantly over first and second generation systems,” according to the paper.

Learn more: climate change and the Winter Olympics

Here’s a short reading list of journalism stories I found helpful in understanding the topic:

‘We’re Rolling the Dice.’ What Climate Change Means for the Winter Olympics. Sean Gregory, Time, January 27, 2026.

As the Winter Olympics Stares Down a Warming Future, Organizers Must Adapt, Scientists Say. Kiley Price, Inside Climate News, January 27, 2026.

Italian expert’s manufactured snow will play big role at the Milan Cortina Games. Jennifer McDermott and Pat Graham, Associated Press, January 23, 2026.

As Winter Warms, Olympic Athletes, Organizers Hunt for Elusive Snow. Eric Niiler, The New York Times, January 21, 2026.

To survive warming winters, the Olympics will need to change. Bob Henson, Yale Climate Connections, January 21, 2026.

What Artificial Snow at the 2022 Olympics Means for the Future of Winter Games. Chad de Guzman, Time, February 8, 2022.

Snowpack update: still dismal across most of the West

As I noted in my previous post, much of the West is experiencing a major snow drought, with some locations recording their lowest snowpack in many decades.

I’m sorry to say that not much has improved, and the clock is ticking on this season—for example, the median peak for Colorado’s statewide snowpack is April 8.

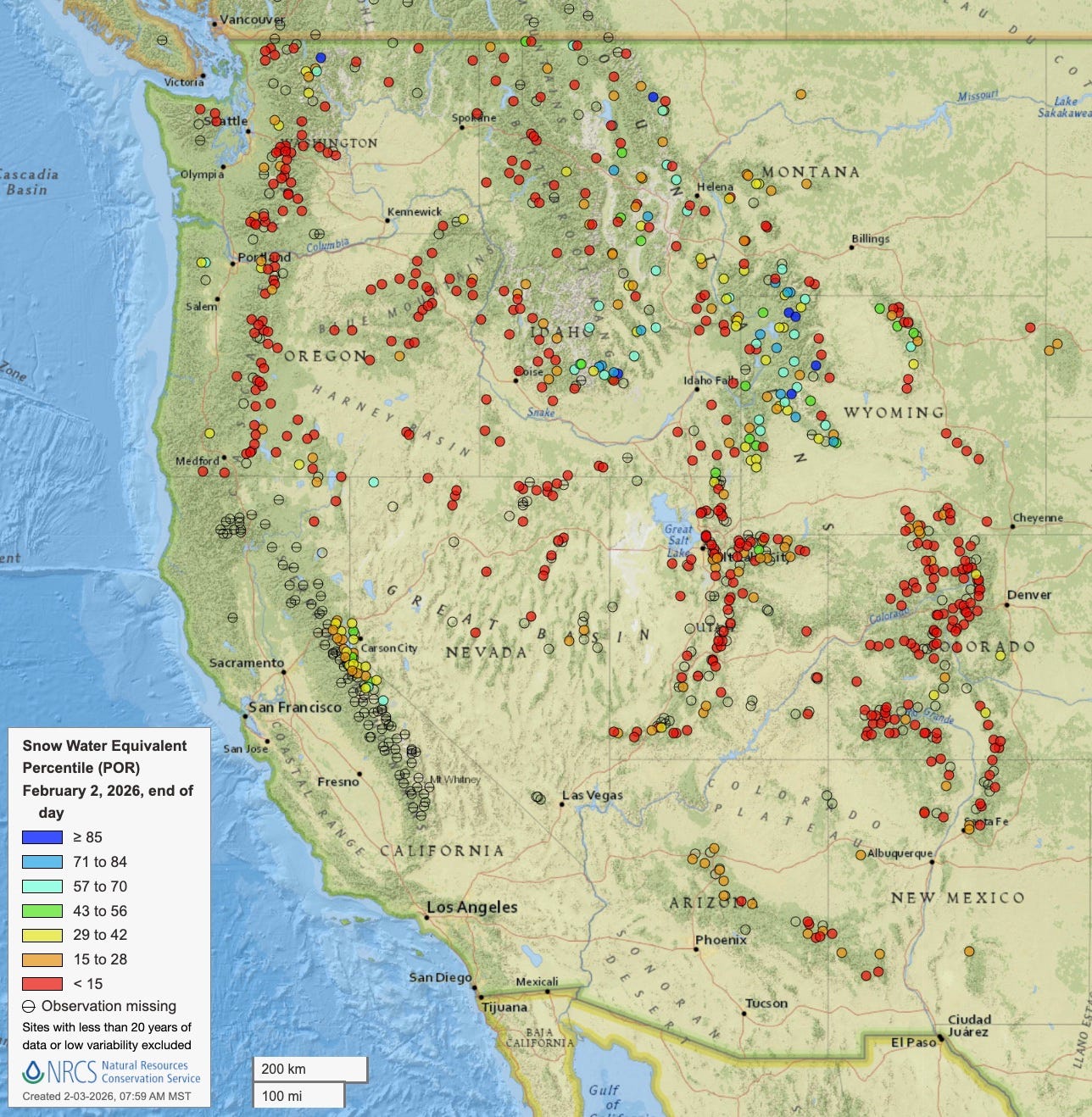

In the February 2 map below, all of those red dots indicate monitoring stations where the snow water equivalent is below the 15th percentile. Ugh!

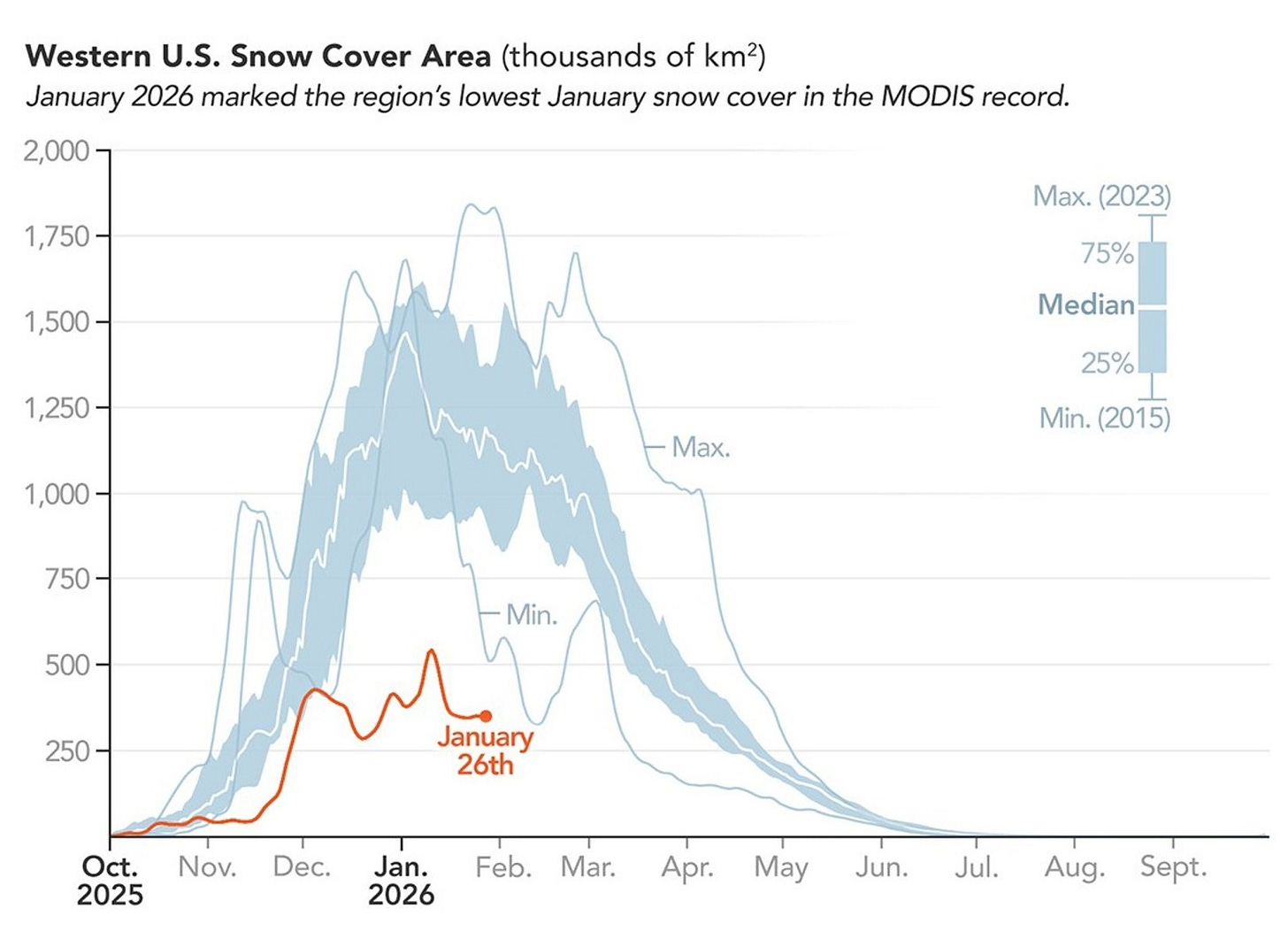

Another way to gauge the snowpack is to map how much land it’s covering using satellite imagery. The chart below from NASA shows that Western U.S. snow cover was tracking at record-low levels for January, based on satellite observations dating back to 2001. More recent data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center show the record lows have continued into February. Oy!

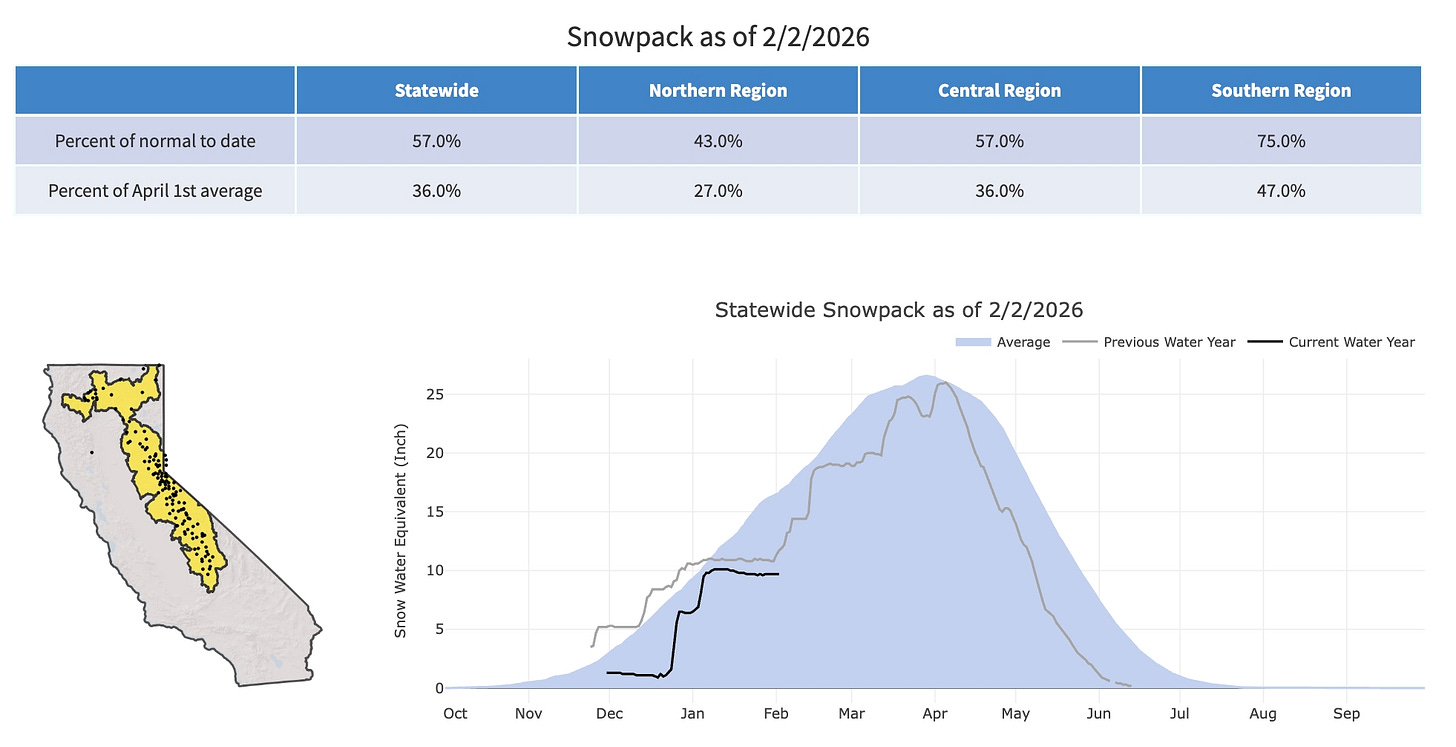

After a slow start this season, California’s overall snowpack was looking OK in early January. The graphic below, however, shows that statewide snowpack (black line) was at just 57% of normal on February 2. “Despite the lack of snow, California has ample water this year, with good rainfall and major reservoirs at 124% of their average levels after three years that brought average or above-average snow,” writes Ian James at The Los Angeles Times.

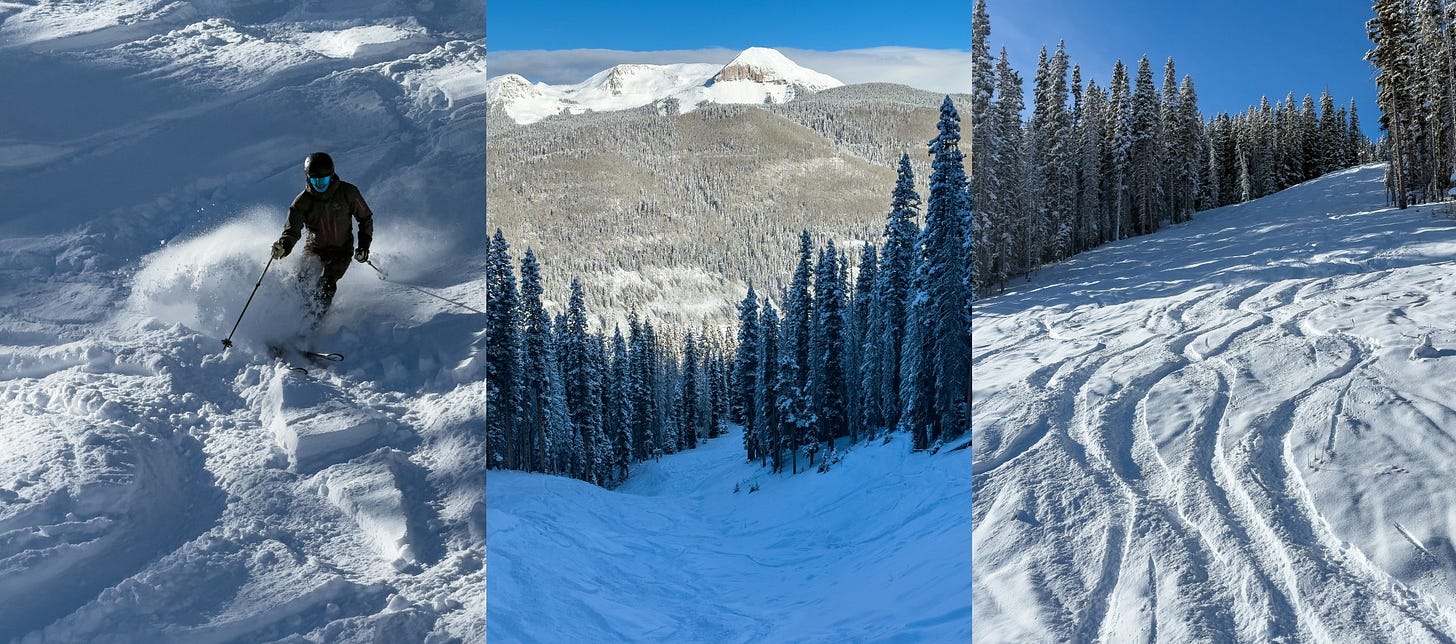

Precious powder day at Purg

This season, I’ve shot and shared lots of photos of abysmal snow conditions at ski areas. So, in the interest of being a fair and balanced journalist, I feel obligated to show the other side of the story: we finally had a legit powder day on January 24 at Purgatory.

The resort reported 12 inches from the storm, though my own probing with a ski pole didn’t find quite that much. Checking a resort’s snow report can sometimes feel like asking a barber if you need a haircut. Even so, this was easily my best day of the season. It felt both great and strange to make soft turns again—rather than scraping my skis across bulletproof ice, with rocks and plants still peeking through.

Although no new snow has fallen at Purgatory since the last storm, next week’s forecast at least offers a glimmer of hope, with some substantial snowfall possible across the West. Catching up to average feels increasingly unrealistic in Colorado and many other Western states—but in a season like this, we’ll take whatever comes.

The irony of needing massive refrigeration and snowmaking machines (that produce emissions) to combat climate change at the Winter Olympics is absolutly wild. Maybe they should just hand out gold medals for who can produce the most artifical snow at this point.