Photo essay: Low tide in Colorado

Images from a thin winter

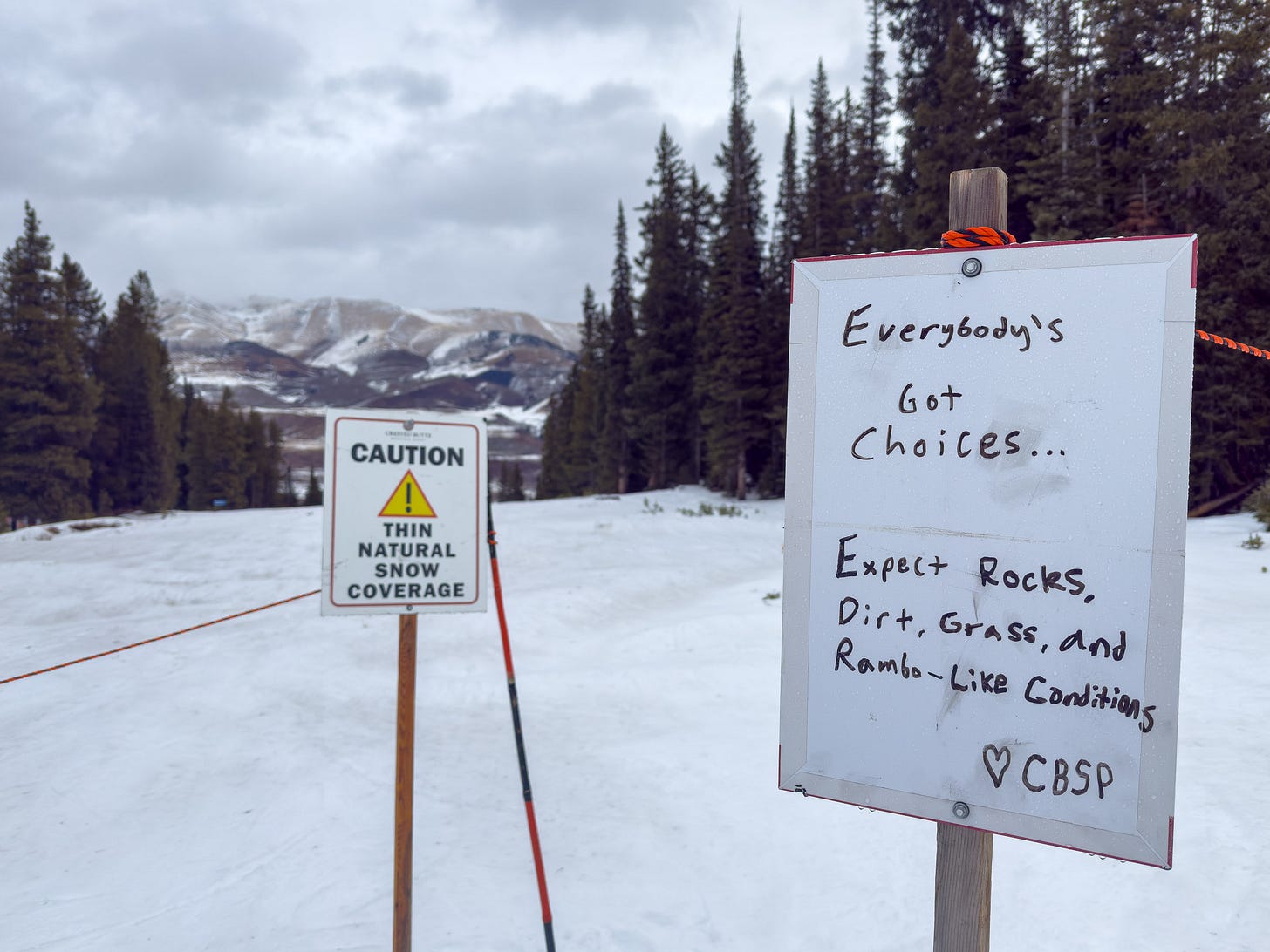

Colorado’s snowpack was dismal, but that didn’t stop me from going on a ski road trip across the state over winter break.

Over six days, I skied five resorts—Purgatory, Crested Butte, Breckenridge, Loveland, and Monarch—and conditions were lousy at all of them. I went into the trip with very low expectations, and I wasn’t disappointed.

Even so, I did enjoy the change of scenery and the chance to visit mountains I hadn’t skied in a long time. What follows is a photo essay featuring the bad, the ugly, and a bit of the good from the solo trip.

Across much of the West, a subpar snowpack is doing more than spoiling ski seasons—it’s raising the risk of wildfires, water shortages, and ecological stress later this year.

Purgatory

December 24, 2025

On the way out of town, I did some laps at my home mountain and continued this season’s trend of abusing the bottoms of my skis due to thin or nonexistent cover.

We had a wet fall in southwest Colorado and the rest of the state, but it was also very warm, so rain fell instead of snow. The above-normal temperatures continued into December, which was on the dry side, so like many ski resorts, Purgatory has struggled to produce enough machine-made snow to make up for what Mother Nature hasn’t delivered.

At Purgatory’s base, I cringed at all the bare spots, some of which were also peeking through on open runs higher on the mountain. Two kids were riding a sled down the gentle slope, only to come to a screeching halt where the snow disappeared, yet they didn’t seem to mind.

From Purgatory, I headed north on U.S. 550, which crosses over three mountain passes—Coal Bank, Molas, and Red Mountain—that are all roughly two miles above sea level. Even at those lofty elevations, the snow was scarce. During winter, this gorgeous stretch of highway can get icy and snowpacked, making the curvy route a white-knuckle affair. This time, it was smooth sailing on dry pavement flanked by exposed dirt.

Crested Butte

December 25, 2025

On a gloomy Christmas, Santa delivered rain to Crested Butte. Humanity’s burning of one lump of coal after another has helped make this shift to liquid precipitation more likely—though it’s tough to definitively attribute this one season’s weather to climate change (see this story from Colorado Public Radio for more on that).

Driving up to Crested Butte from my motel in Gunnison, the rain spattering on the windshield was disconcerting, especially since Gunnison is known as Colorado’s icebox because frigid air often pools in the valley during winter.

As with the other resorts I visited, Crested Butte had very limited terrain open. But some of those runs were surprisingly fun to ski because of the warm weather. Overnight, the slopes hadn't frozen solid, so the turns were soft and forgiving, almost like spring conditions.

The precipitation held off during my first hour, but then it started to rain with gusto at lower elevations, changing to a wintry mix as I ascended the mountain on the chairlifts.

Hoping to advance science, I opened a phone app that lets volunteers report the type of precipitation they’re observing so researchers can better understand the crucial rain-snow transition in mountainous environments. The app, which I wrote about in the story below, records your location and elevation, so it was interesting to do a transect on the chairlift ride and log how the weather changed with increasing altitude.

Loveland

December 26, 2025

As one of the highest-elevation resorts in the nation, Loveland tends to open early and close late in the season, so I’ve skied there in every month from October through June.

Although Loveland’s base is at nearly 11,000 feet and its terrain tops out just above 13,000 feet, there were still big brown patches along the Continental Divide when I visited. On the chairlift, I commiserated about the lack of snow with an old timer who told me he’d been wearing shorts and a t-shirt in Denver the day before.

Before heading back to my motel in Dillon, I drove up nearby Loveland Pass to check the conditions and was stunned by the lack of snow cover above 12,000 feet in late December.

Breckenridge

December 27, 2025

The Saturday between Christmas and New Year’s Day is often one of the busiest times at Colorado ski resorts, but it was eerily quiet at Breckenridge on the day I visited.

Weeks before, when I was planning my trip, I was bracing for big lines at Breck, thinking the place would be mobbed during winter break with out-of-state tourists and Colorado natives from the Front Range. But the queues for the chairlifts were small. And the lodges that would normally be packed with people paying outrageous prices for mediocre food had plenty of available tables.

The place wasn’t completely empty. Many people who had already purchased plane tickets and non-refundable hotel rooms went through with their travel plans. One guy next to me on a chairlift had come out from San Francisco. I apologized for the dreadful conditions, telling him this was the worst start to a ski season I’ve seen since moving to Colorado more than 17 years ago.

Monarch

December 28, 2025

Monarch offered my first powder day of the season—sort of.

Overnight, the mountain received 1” of new snow, but it was super windy, so some of it had blown off by the time I arrived the next morning. It was 11 degrees when I pulled into the parking lot, and the windchill was below zero, but it actually felt good to feel cold during ski season after such a warm start.

Monarch had more terrain open than other resorts, including some steeper black-diamond runs, but the low-tide conditions meant there were lots of ski-wrecking rocks lurking beneath the snow, known as “sharks.”

The night before, in the parking lot of my Salida motel, I dripped molten plastic from a flaming p-tex candle into the many gouges in my bases. The patches didn’t hold at Monarch, and I picked up some more core shots along the way, making me wonder how much longer my 2017 Rossignol Soul 7s would last.

Crested Butte

December 29, 2025

On the way home to Durango, I made an encore visit to Crested Butte, which looked much better clad in white. It even dipped to minus-5 degrees on my drive up from Gunnison.

The storm that brought 1” to Monarch had dropped 7” on Crested Butte. Unfortunately, that fresh snow attracted crowds, so by mid-morning I was waiting in 15-minute lift lines to access the still-limited terrain (people fleeing Telluride—which was closed due to a ski patroller strike—may have also increased visitation).

At Crested Butte, the fresh powder had been skied off the day before, and the slopes were now rock hard from the freezing temperatures.

Upon returning to Durango, the guy at the ski shop gently advised me it was time to convert my aging Soul 7s into “rock skis”—shitkickers meant for marginal conditions, which may be the new normal. After nearly 250 days of service, I’d certainly gotten my money’s worth.

Fortunately, I was able to snag a pair of the Soul 7’s successors online for less than half price, thanks to my ski instructor discount. But given the lack of snow this season, I’ll continue beating up my old skis for the foreseeable future. Even with new snowfall since my trip, Colorado’s snowpack remains far below normal.

Rage against the stoke machine

The skiing was disappointing, but for an environmental journalist on the doom-and-gloom beat, it was a fruitful reporting trip. Sharing bad news is my specialty.

Most of today’s snow and ski journalism is low-value, high-volume fluff that typically accentuates the positive while sidestepping the climate context. The content tends to fall into two camps: fawning advertorial—press releases lightly rewritten to flatter resorts and gear companies—or clickbait engineered to game search engines and social media algorithms through listicles, storm hype, and a steady drip of alpine tragedies that can read like ghoulish tabloid coverage.

My goal here is different. I’m pursuing independent snow journalism that aims to illuminate what’s happening to our snowpack, explore how scientists are studying it, and explain why it all matters for society—even when the news is grim and doesn’t enhance advertising revenue or readers’ stoke.

I want to educate and enlighten, not promote and pretend. I want to analyze data, not traffic in vibes.

That can be a lonely, unprofitable pursuit in a media landscape built around short attention spans and lifestyle enthusiasm. But I believe it’s more important than ever to honestly bear witness to a changing cryosphere—and to document what’s actually happening on the ground.