Snowpack update and G is for "glacier"

Plus: turkeys digging snow

The snowpack here in southwest Colorado got a much-needed boost last week thanks to a storm that dumped more than a foot at the snow.news headquarters and shut down the Durango public schools on Valentine’s Day.

The atmospheric river also deepened the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and other mountain ranges in the West, but conditions remain bleak in Arizona and New Mexico, as shown in this map of snow water equivalent (SWE):

Below are two additional views of the SWE data, with the first map showing smaller basins and the second map plotting the values for individual SNOTEL stations, rather than for watersheds.

At home, anticipation ran high in the days leading up to the Valentine’s Storm, and I braced for disappointment.

The pending storm was a hot topic at my daughter’s elementary school, where the kids were sharing superstitions that are supposed to coax flakes from the sky and cause a snow day, including:

Yelling “snow day” into the freezer

Putting spoons under pillows

Flushing ice cubes down the toilet

Putting on pajamas backward and inside out

In the end, school was canceled, and the storm wound up overproducing in our neck of the woods. The charts for our local snowpack show a pronounced jump due to the Valentine’s Day storm, but they also reveal we have a way to go until reaching normal conditions. The February 20 graphic below is for my home basin, the Animas River, where the snowpack has risen to 81 percent of the long-term median, but it’s still only at the 26th percentile.

Looking ahead, the forecast is dry over the next week here in the Four Corners and in the surrounding region, including the headwaters for many key rivers such as the Colorado and Rio Grande. The map below shows the expected precipitation anomaly over the next seven days.

Yesterday, the Climate Prediction Center released its latest three-month seasonal outlook for the U.S. Drought Monitor. The map below shows that drought is expected to expand throughout many parts of the West (yellow shading), though some improvement is projected in the northwest portion of the region.

SnowSlang: G is for “glacier”

For The Water Desk, I recently published an illustrated glossary of snow-related terms, building upon my SnowSlang project. One of the more extensive entries is for glaciers and glacial landforms, which I’ve shared below.

I grew up on Long Island, a terminal moraine formed in the last Ice Age, and I now live in a landscape carved by the mighty glacier that occupied the Animas River Valley, just a moment ago in geologic time. Accordingly, I’m fascinated by glaciers’ lasting imprint and the extensive vocabulary associated with their ebb and flow!

A glacier is a large, perennial mass of ice and snow that moves slowly downhill under the influence of gravity. A glacier will form if the accumulation of snow and ice exceeds their loss through ablation (via melting, evaporation, sublimation, and other forces).

As the snow accumulates, it compresses over time, turning into firn before becoming glacial ice, as shown in the illustration below.

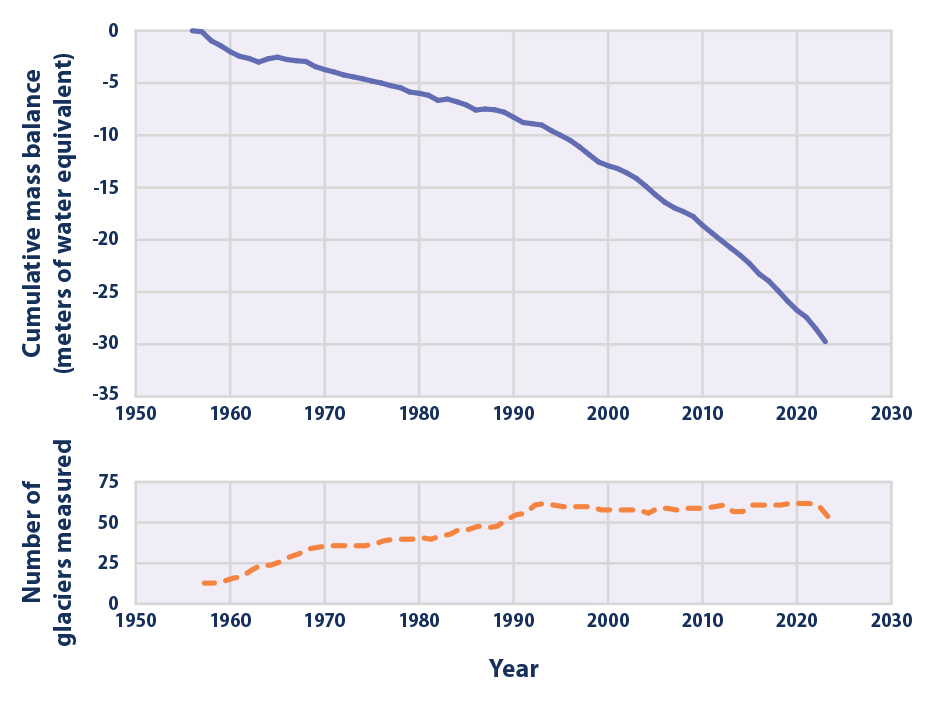

Glaciers around the globe are threatened by warming and are used as a barometer of climate change effects. The graphic below, from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, shows a precipitous decline in reference glaciers around the planet from 1956 to 2023.

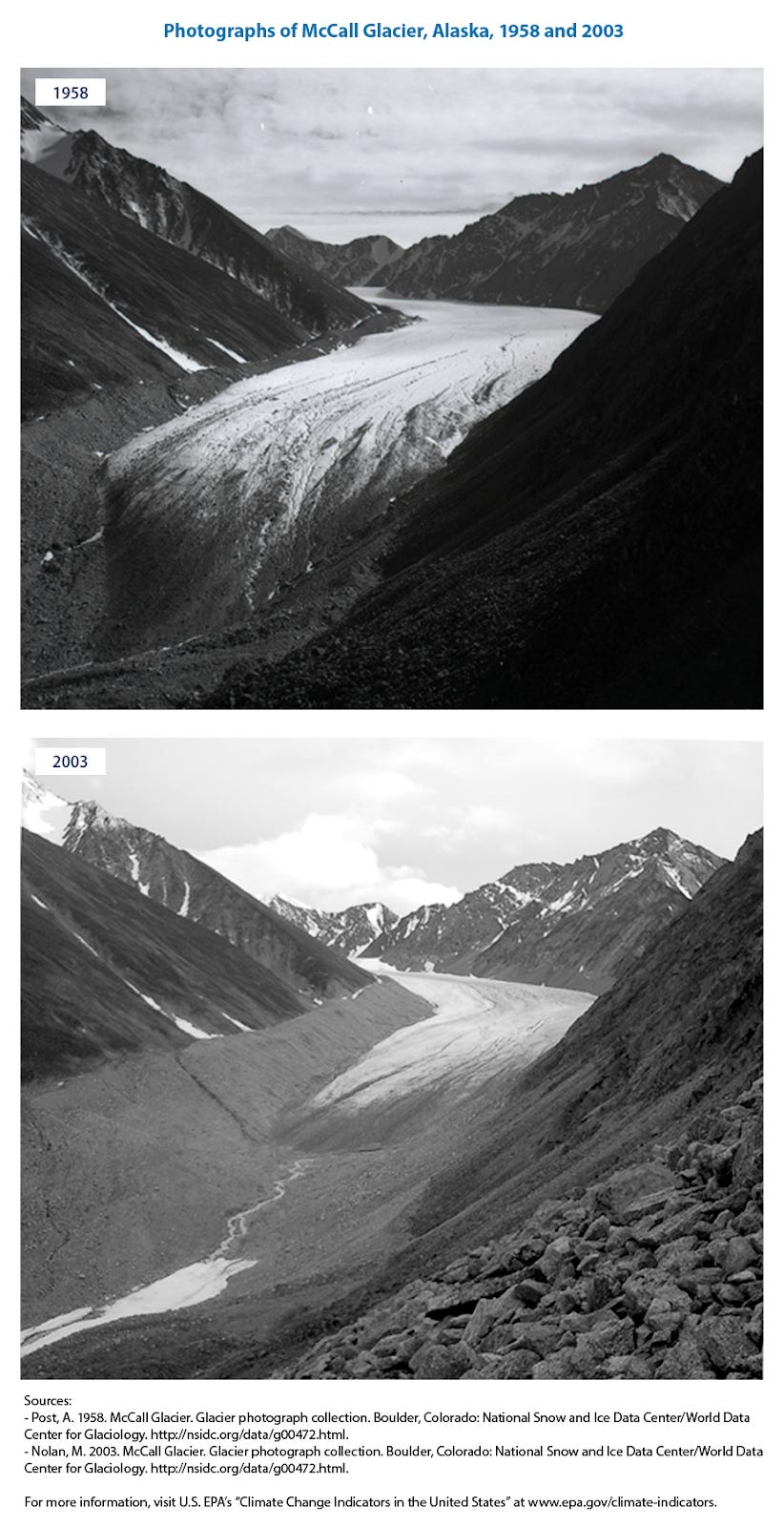

The photographs below show how Alaska’s McCall Glacier changed from 1958 to 2023.

Past Ice Ages covered many of the West’s mountains in ice, and the current landscape still reflects these past glaciations, which both erode and deposit material. At the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, around 20,000 years ago, about one-quarter of the Earth’s land area was covered by glaciers.

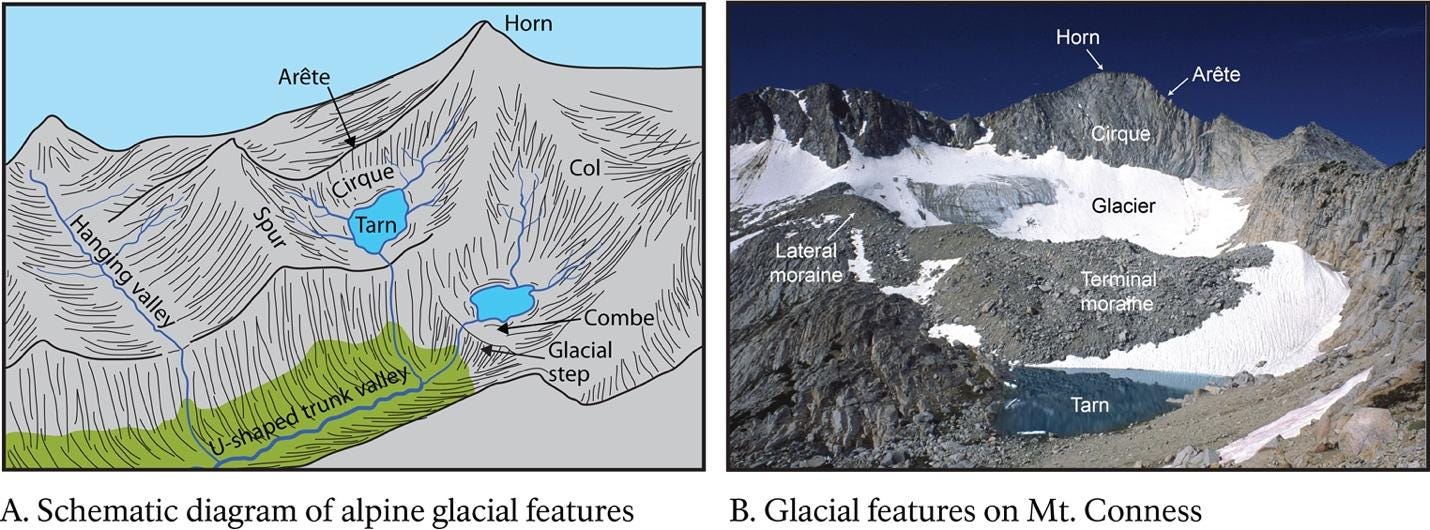

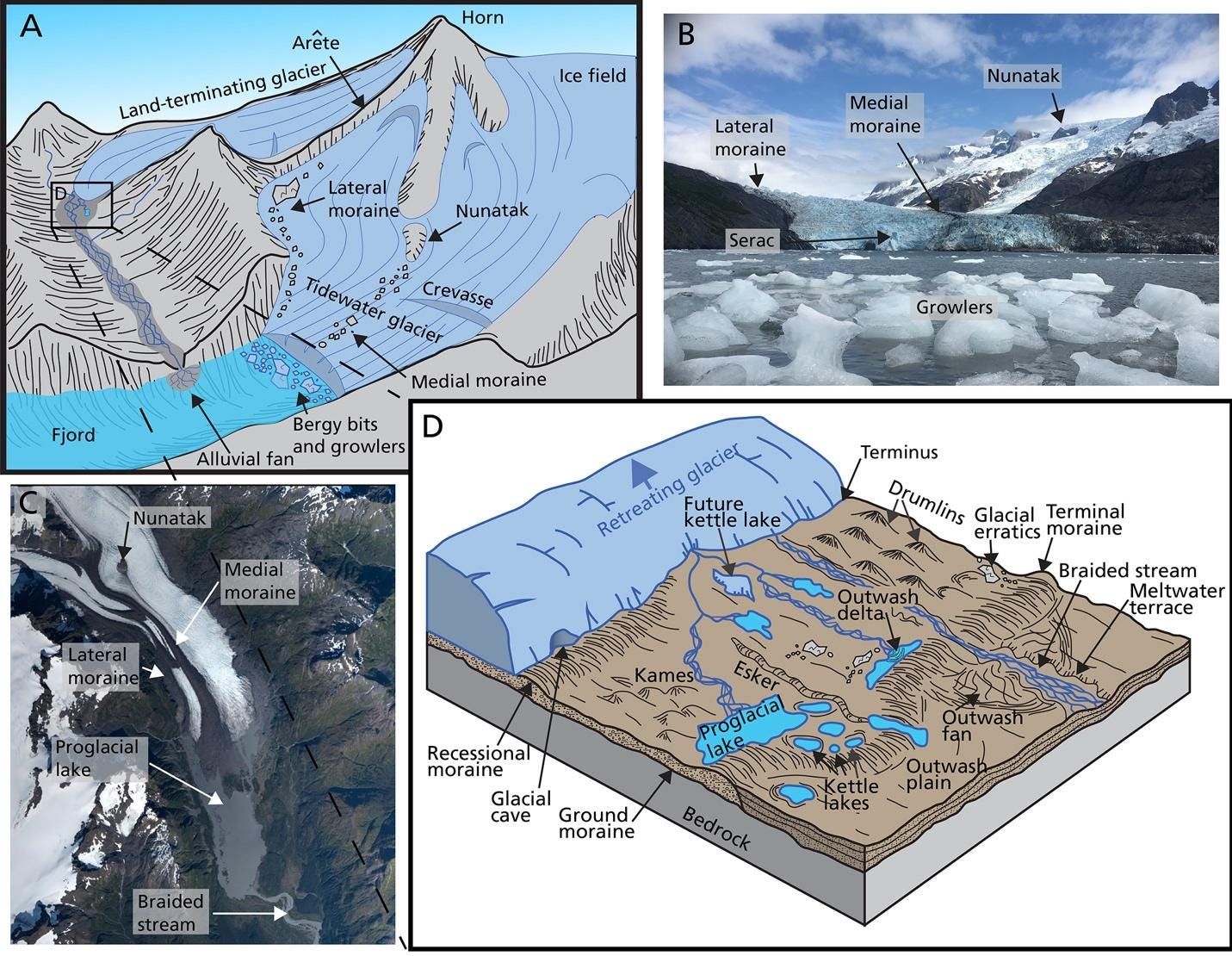

The diagrams below show some common glacial landforms, followed by definitions of terms most relevant to the American West.

Mini-glossary of glacier-related terms

Arête: sharp, narrow ridge formed between two cirques or glacial valleys

Cirque: bowl-shaped depression carved by a glacier at the head of a valley

Col: saddle-shaped pass between peaks formed by two glaciers on either side of a ridge

Comb: jagged ridge caused by glacial erosion

Crevasse: deep crack in a glacier’s surface caused by stresses from the ice’s movement

Drumlin: elongated hill of glacial sediment shaped by the flow of ice

Esker: long ridge of stratified sediment deposited by meltwater streams flowing beneath a glacier

Firn: snow that has been compacted and crystallized but not yet converted to glacial ice

Glacial erratic: rock or boulder transported by a glacier far from its origin

Glacial step: step-like formation caused by differential erosion in glacial valley

Hanging valley: a tributary valley at a higher elevation due to glacial erosion of the main valley; often includes a waterfall

Horn: pyramid-shaped peak formed by the erosion of at least three cirques

Kettle lake: depression formed by the melting of a block of ice in glacial outwash

Mass balance: the difference between the amount of snow/ice gained through accumulation and the volume of snow/ice lost through ablation; glaciers grow due to a positive balance and shrink due to a negative balance

Moraines: deposits of glacial sediment, including terminal (at the toe of a glacier), lateral (along the sides of a glacier) and medial (when lateral moraines join at the intersection of glaciers)

Nunatak: a peak that protrudes above the surrounding glacier or ice sheet and is not covered by ice

Outwash plain/delta/fan: formation created by the deposition of sediment as meltwater flows out of a glacier and deposits sand/gravel in a spreading formation

Tarn: small mountain lake in a cirque

U-shaped valley: a valley with a wide, relatively flat floor and steep sides, formed by the carving of a glacier (in contrast to a V-shaped valley caused by river erosion)

Where are glaciers in the West?

According to the Glaciers of the American West, an online resource by Portland State University researchers, there are 8,348 glaciers in eight Western states, not including Alaska, with the most by far in Washington. These glaciers and permanent icefields range from “rivers of ice on Mount Rainier that are over 8 km (5 mi.) long to tiny patches of ice in the Rocky Mountains not much larger than a city block,” according to the site.

The diagram below shows the general locations where the remaining glaciers are found in the American West—not all purple areas are perennially frozen!

Turkeys digging snow

In an earlier post, I shared a video of a crow skiing down a roof. The footage below isn’t quite as cool, but I was excited to recently film a bunch of wild turkeys around home doing some snow removal to search for a meal:

These Merriam's turkeys are omnivores, and the species has been recorded eating 78 kinds of food, according to a 1996 study of their ecology in South Dakota. Their preferred winter meal was ponderosa pine seeds, but they also eat other vegetable matter and arthropods.

I’ve seen a lot of turkeys this winter, maybe because the neighborhood has been so lacking in snow cover until recently and they’ve had such easy pickings around here.