Latest snow news and ski movie trailers

Plus: B is for "bomb cyclone"

Early-season snowpack update

Today is the last day of the first month of the 2024-2025 water year, so I took a quick look at how the snowpack is doing in the West.

I have some reservations about sharing the map below because early-season snowpack figures displayed in this way can be deceptive. At the start and the end of the season, these numbers can bounce around wildly from day to day and from storm to storm. The figures now range from 0% to 1,950% of the long-term median, but those extremes won’t last. FWIW, it’s a slow start in the Northern Rockies, while the Pacific Northwest, Utah, and Colorado are doing better.

At the end of October, charts like the one below are more instructive since they show just how far we have to go in the accumulation season. In the graphic, the black line shows the snow water equivalent for Colorado’s statewide snowpack, and the green line indicates the median for 1991 to 2020. The two spikes in the black line show the pair of October storms. One month into the water year, Colorado’s snowpack is at 155%, but we’ve got 160 days until the median peak date of April 8.

How soon until betting markets let you wager on the snowpack? I, for one, would engage in emotional hedging: putting money down on a subpar snowpack so I’d have some winnings to console me.

snow.news is good news

Blame it on the autumn heat, but it’s been a while since I’ve posted a rundown of the latest snow-related news. Below are some pieces that have been on my radar over the past couple of months.

New NASA Instrument for Studying Snowpack Completes Airborne Testing. NASA Science Editorial Team, 10/29/24

Revisiting La Niña and winter snowfall. Tom Di Liberto, ENSO Blog, 10/24/24

Baltazar Ushca, ‘last iceman’ of Ecuador’s highest peak, dies at 80. Brian Murphy, The Washington Post, 10/23/24

Atmospheric rivers are shifting poleward, reshaping global weather patterns. Zhe Li, The Conversation, 10/11/24

Snowflake dance analysis could improve rain forecasts. University of Reading press release, 10/9/24

In High Mountain Alaska, a Glacier’s Deep Secret Is Revealed at Last. Raymond Zhong and Jason Gulley, The New York Times, 10/8/24

My pilgrimage to the vanishing Sphinx snow patch. Danielle Fleming and Morgan Spence, BBC, 10/7/24

Large French Alpine ski resort to close in face of shrinking snow season. Kim Willsher, The Guardian, 10/7/24

Is California Getting Drier? Sarah Bardeen Q&A with Benjamin Cook, Public Policy Institute of California, 10/1/24

The storm chasers trying to save the world from drought. Jeremy Miller, The Economist’s 1843 Magazine, 9/27/24 (disclosure: a grant from The Water Desk, which I co-direct, helped support this story)

The survival rate for avalanche burials has increased by ten percent since 1994. Eurac Research, 9/26/24

Latest ski movie trailers

One sign of fall in ski country is the arrival of death-defying ski movies, so I’d be remiss in not sharing a couple of favorite trailers from the annual batch of films now making the circuit.

Like many skiers of a certain age, my love and fascination with snow sports got a boost from watching Warren Miller films in which the alpine scenery was as captivating as the acrobatics.

There was also “Hot Dog…The Movie,” a raunchy 1984 cult classic that came out when I was around 14 years old. It’s the “highest-grossing ski movie of all time,” according to a 2016 Outside magazine “unofficial oral history,” which notes the movie “has a paint-by-numbers plot, loads of sexism and gratuitous nudity, and a screenplay full of tired racial stereotypes.” There’s also lots of amazing skiing—on long, skinny skis—plus the incomparable ski ballet!

I’ll spare you the embed of the trailer for “Hot Dog,” but below are a few of this season’s finest clips. Powder offers its list of top 2024 ski movies here.

The trailer below is from Beyond the Fantasy, the latest release from Teton Gravity Research, which touts itself as the “leading lifestyle brand in action sports media.”

Next up is Calm Beneath Castles, a creation of Matchstick Productions, which describes itself as “the world’s most awarded ski film brand.”

I hope these videos supply some early-season stoke and prime your adrenaline receptors. I’m always in awe of what these folks can do, not only on skis and snowboards but also with cameras, drones, and helicopters.

I’m no freestyle daredevil, but I can’t resist occasionally letting loose and trying a few jumps in the terrain park and beyond, where the air I achieve is typically measured in inches. In Simpsonian terms, my studious Lisa personality morphs into the devious Bart on his skateboard.

It has been fascinating to watch my own daughter, like so many other kids, gravitate toward jumps and other airborne maneuvers, not only on the slopes but in water and on dry land. It’s like some inborn instinct to take flight.

Perhaps we’re jealous of birds or want to soar like our better angels, but it doesn’t take Charles Darwin to see the evolutionary basis of such adventurous behavior. Surely it would have conveyed a survival advantage to our furry forebearers as they swung from trees and then crossed the African savannah, living by tooth and nail while fighting wildlife and each other to the death.

But maybe it’s the birds who are jealous of us skiers and snowboarders? Check out the video below of a crow shredding on a roof!

SnowSlang: B is for “bomb cyclone”

From a meteorological perspective, a bomb cyclone really is the bomb. These rapidly strengthening extratropical cyclones are responsible for extreme storms that can cause intense snowfall, high winds, and flooding. They’re defined by a precipitous drop in atmospheric pressure of at least 24 millibars in 24 hours.

“When a cyclone ‘bombs,’ or undergoes bombogenesis, this tells us that it has access to the optimal ingredients for strengthening, such as high amounts of heat, moisture and rising air,” writes Esther Mullens of the University of Florida. “Most cyclones don’t intensify rapidly in this way. Bomb cyclones put forecasters on high alert, because they can produce significant harmful impacts.”

The term was coined in 1980 by MIT meteorologists Frederick Sanders and John R. Gyakum. In 2018, Gyakum told The Washington Post the name “isn’t an exaggeration — these storms develop explosively and quickly.”

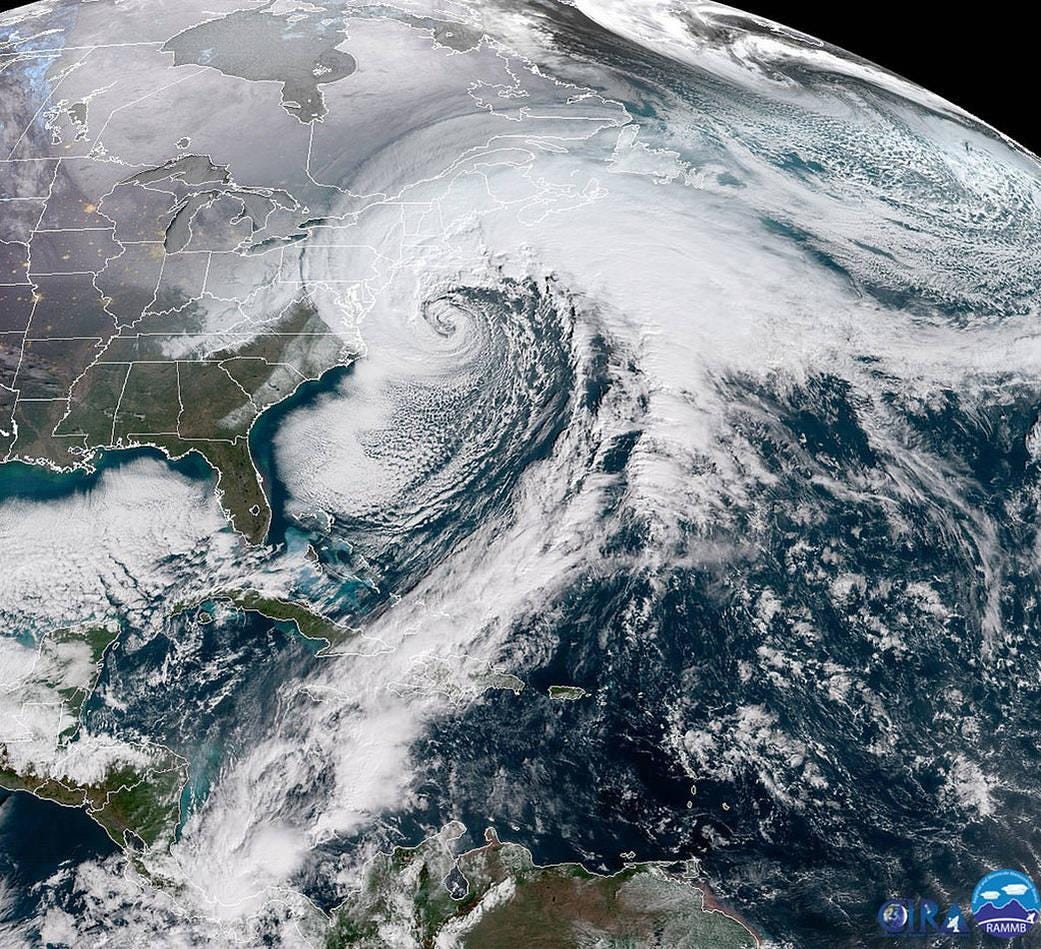

We often hear about bomb cyclones hitting the Eastern Seaboard, where they can draw on the relatively warm waters of the Gulf Stream. The satellite image below shows a classic bomb cyclone. This event was also described as a Nor’easter—a storm along the East Coast characterized by strong northeast winds and heavy precipitation—but not all Nor’easters are bomb cyclones.

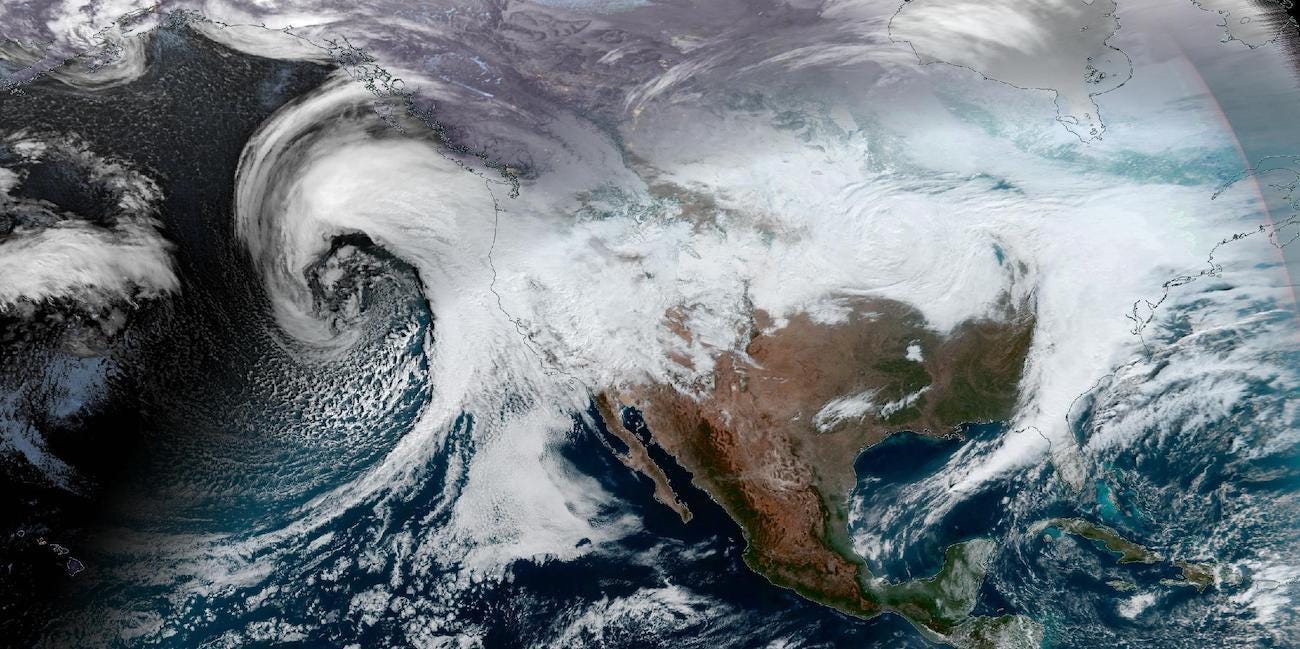

Bombogenesis can also occur in the middle of the country or along the West Coast, as shown by the image below.

See the video below from The New York Times for a visual explainer of bomb cyclones.

That was quite a Halloween costume, Mitch!