Snow drought update: record warmth, thin snowpack

Plus, SnowSlang: O is for "orographic lift"

A serious snow drought is gripping much of the American West as record-breaking warmth has dominated the winter so far.

The stark lack of snow is raising the risk of a dangerous wildfire season later this year in a region where many forests are already choked with excess fuel.

And the anemic snowpack is increasing pressure on the troubled Colorado River, where negotiators remain deadlocked over how to share cutbacks amid declining flows and relentless demands.

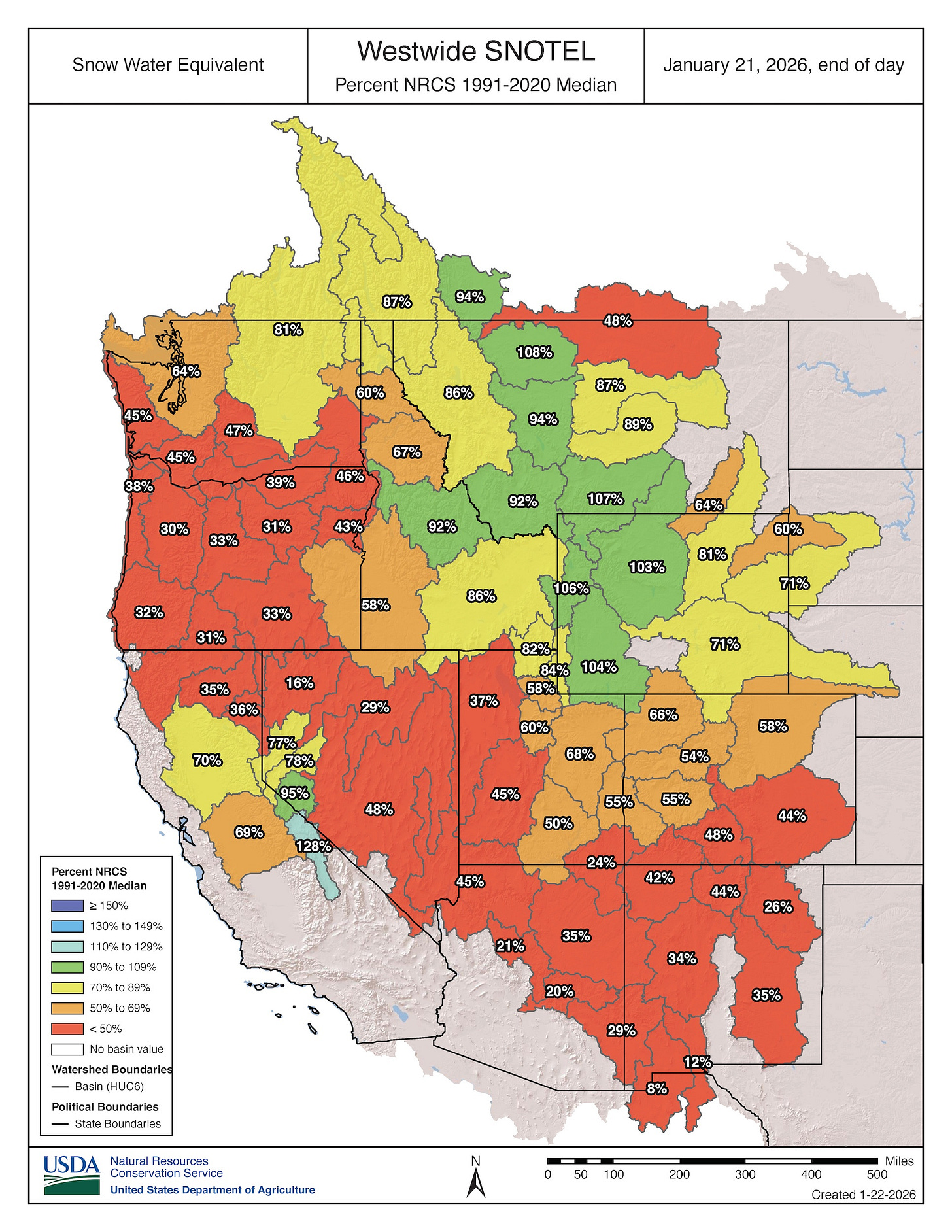

The January 21 map below shows snow water equivalent—a measure of the snowpack’s water content—in river basins across the region. Basins in red are below 50% of the 1991-2020 median; orange indicates 50% to 69% of normal.

In a January 8 update, the National Integrated Drought Information System reported that the West’s January 4 snow cover was the lowest for that date in the satellite record since 2001. “Every major river basin in the West experienced near-record or record warmth through December 2025, inhibiting the accumulation of snow,” according to the update.

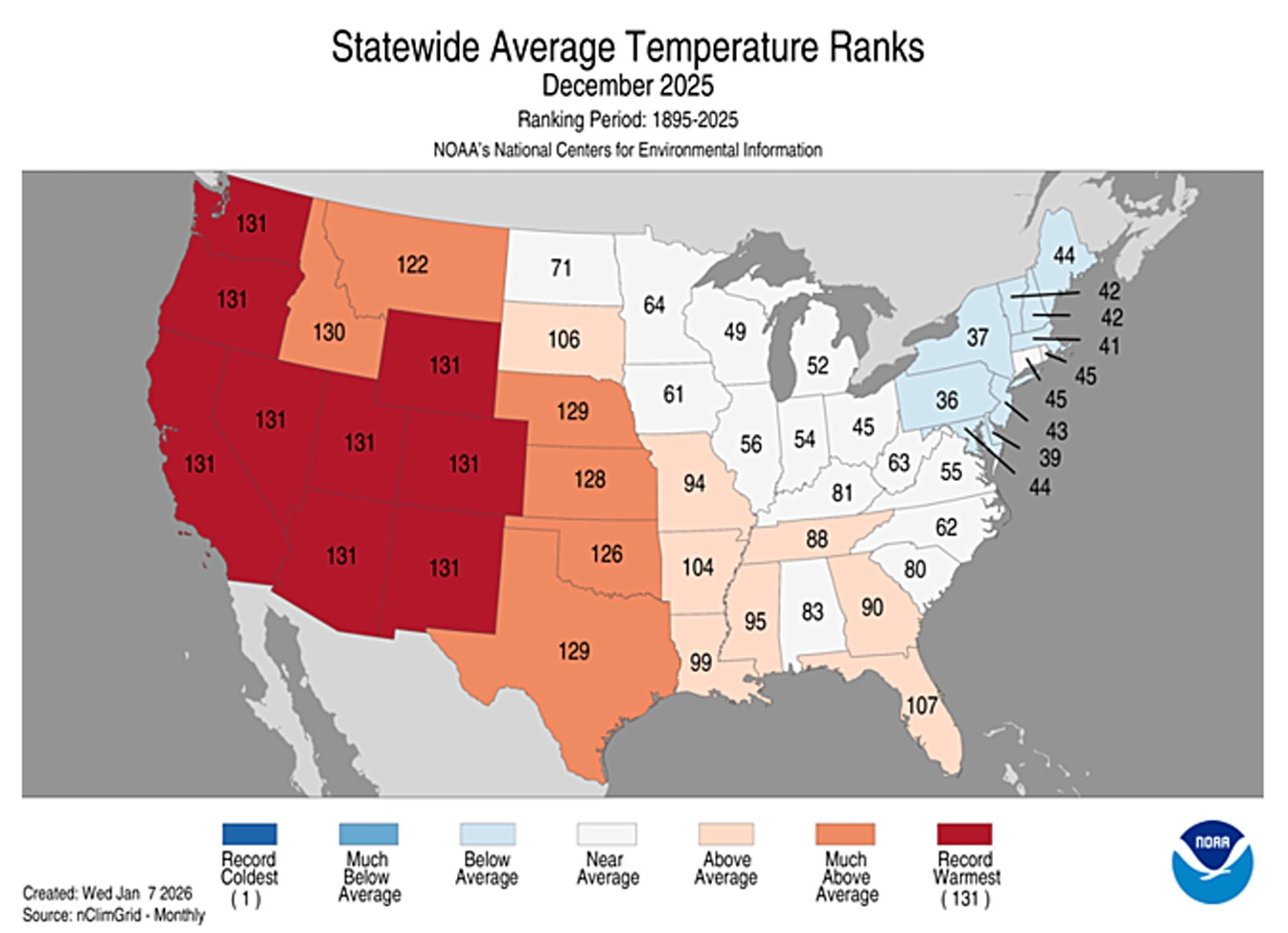

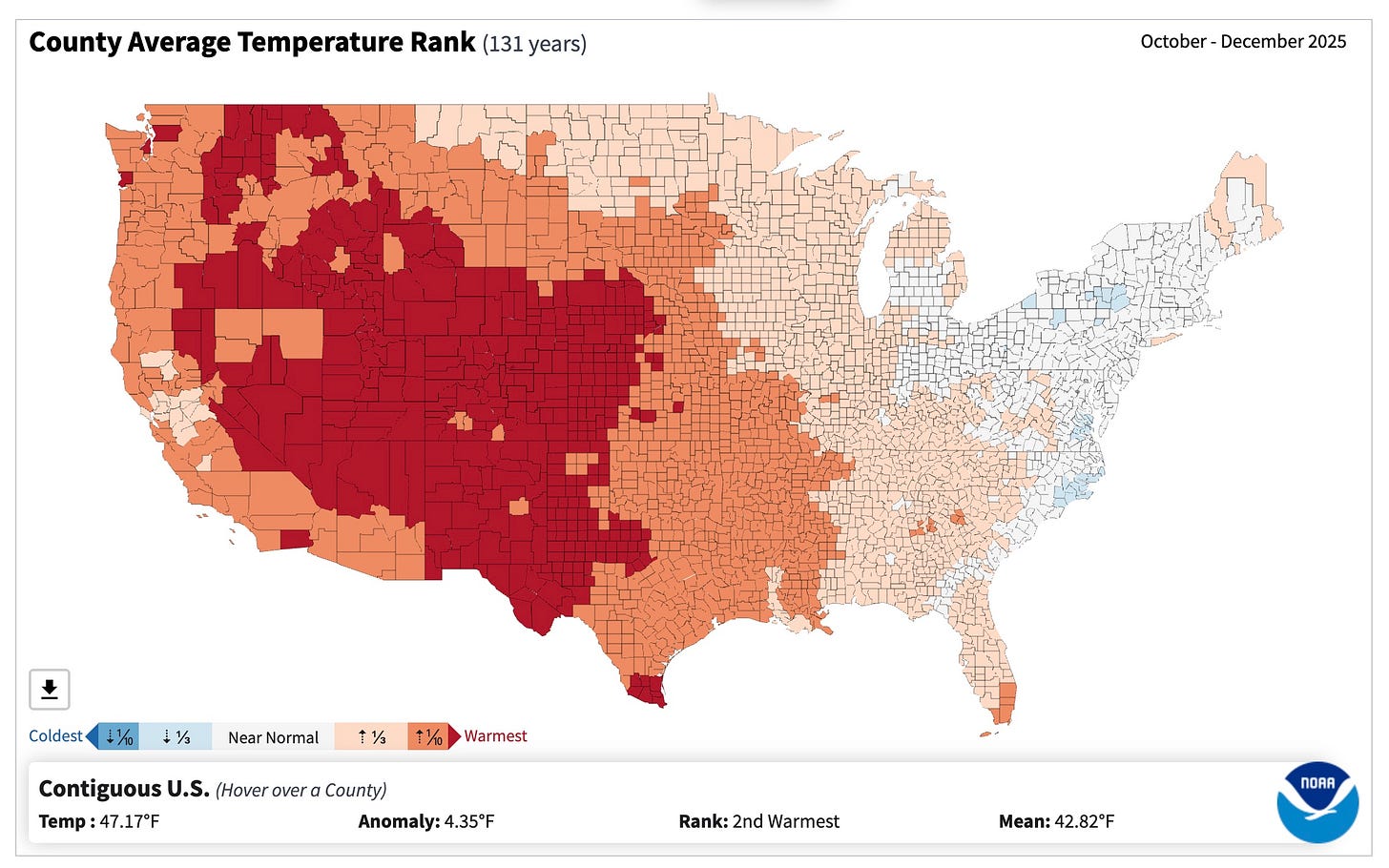

The graphic below shows statewide temperature rankings for December 2025. Nine Western states had their warmest December on record (dating back to 1895), and Idaho had its second-warmest.

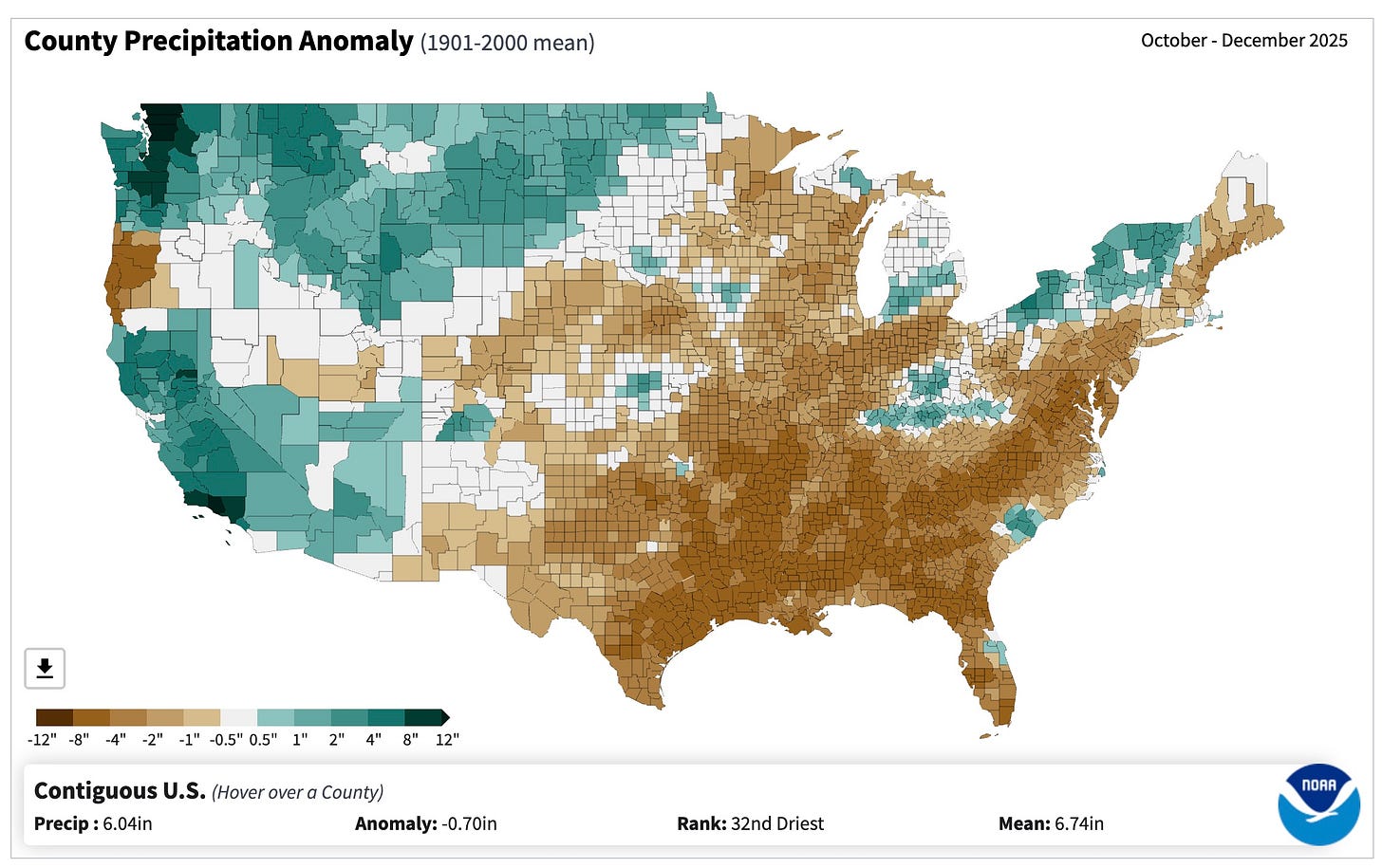

Drilling down to the county level, the two images below show temperature and precipitation from October through December. The top panel illustrates that many Western counties experienced their warmest three-month period since 1895 (red shading). The bottom map compares precipitation to the 1901–2000 average—and reveals that many of those same areas were actually wetter than normal during the last three months of 2025.

In parts of the Pacific Northwest, for example, this winter has brought a “warm snow drought,” where higher temperatures—not a lack of moisture—have prevented snow from piling up. In other places, precipitation has also been below normal, creating a “dry snow drought.”

The West’s lean snowpack has also hurt ski areas, which have struggled to open terrain—and make snow during warm spells. I skied Crested Butte over the MLK Day weekend, and the lack of lift lines during a normally busy holiday was striking.

Last week, Vail Resorts reported that visits to its resorts were down sharply, primarily due to the lack of snow. In the Rockies, only about 11% of the company’s terrain was open in December because snowfall was nearly 60% below the 30-year average, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Here in southwest Colorado, a local ice-fishing tournament at Vallecito Reservoir was cancelled because the lake was ice-free.

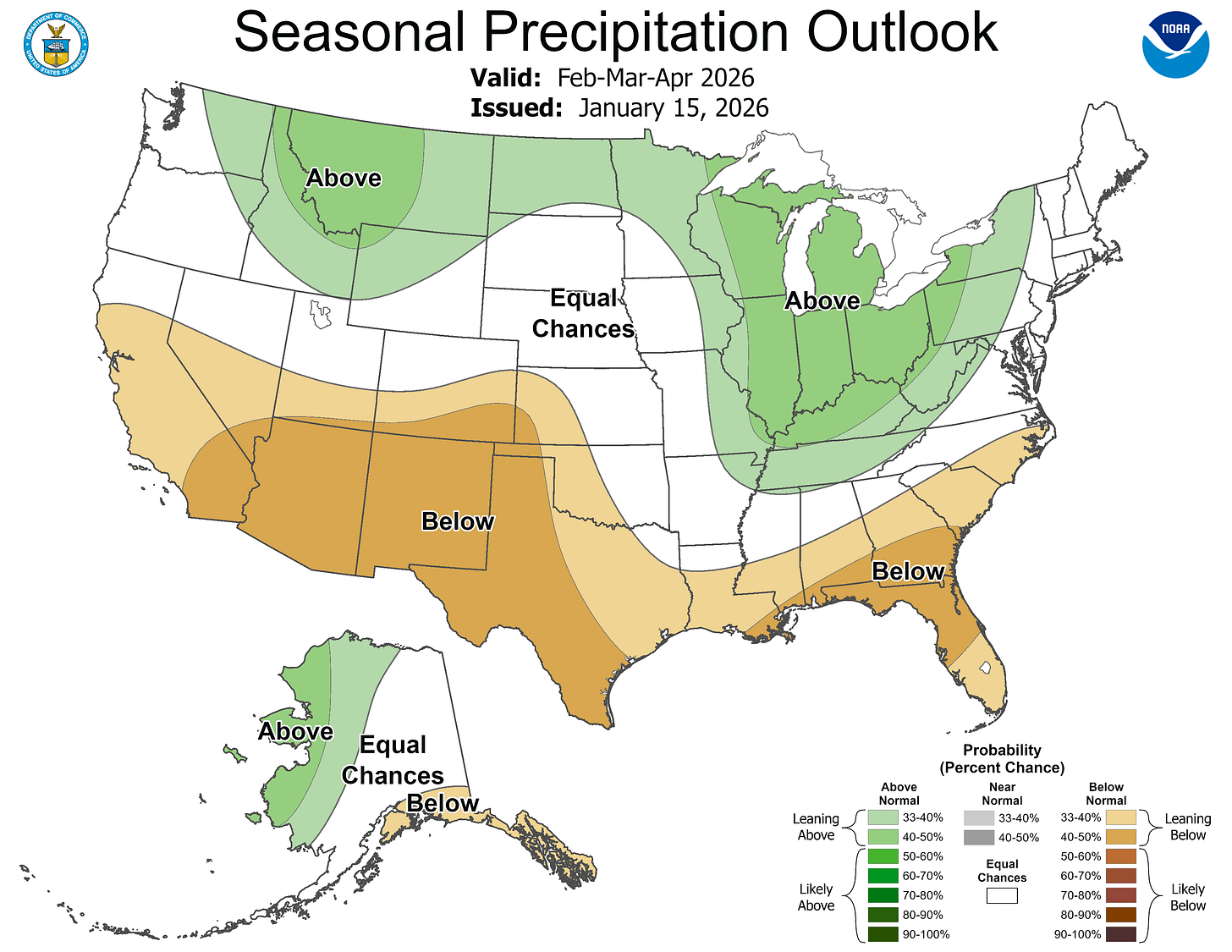

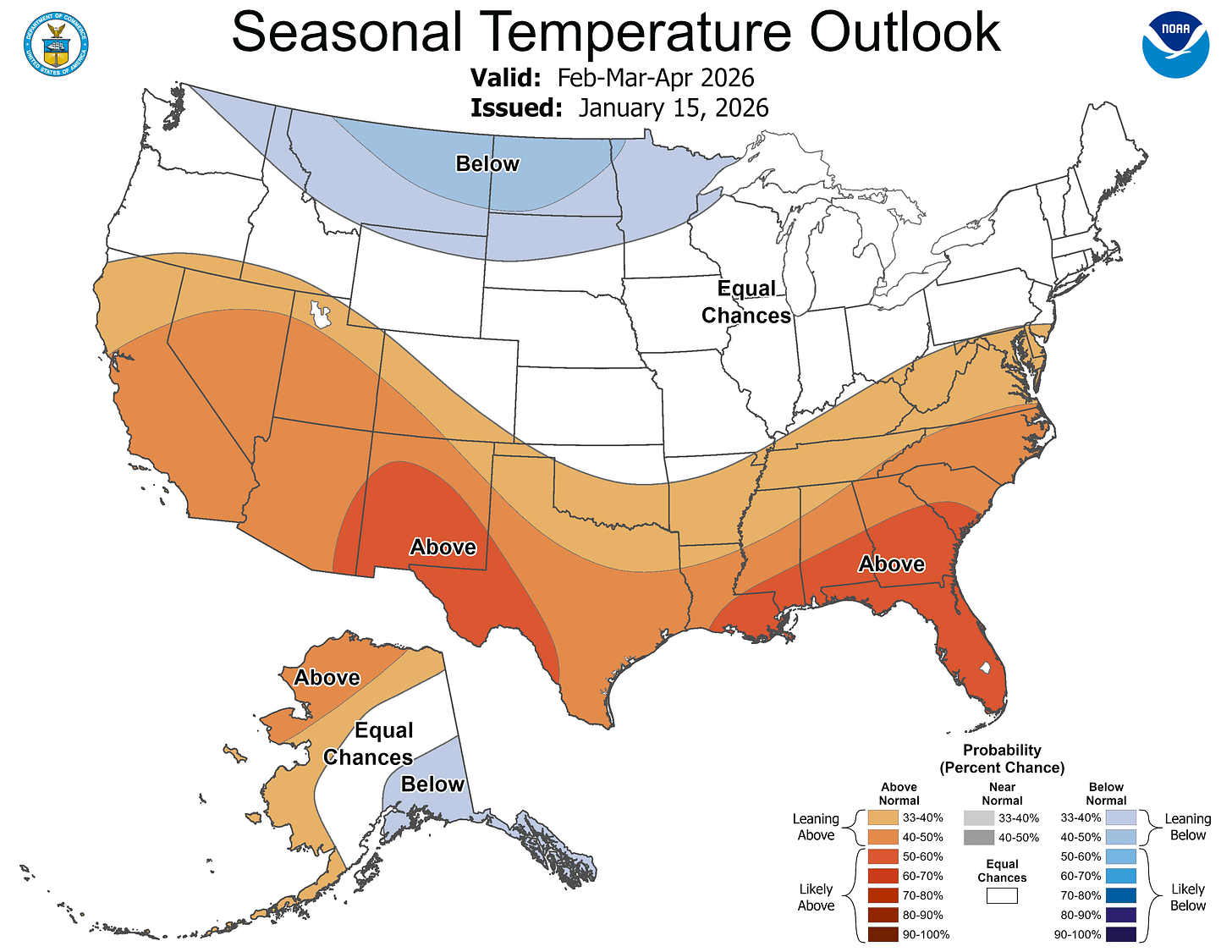

At this point, many parts of the West could use a Fabulous February, a Miracle March, and/or an Amazing April to build the snowpack to respectable levels. Forecasting months ahead is very challenging, but the January 15 maps below from the Climate Prediction Center tilt toward warmer, drier conditions across the southern tier of the West from February through April. The Northern Rockies, meanwhile, are projected to be cooler and wetter than normal.

Although we’re currently in a La Niña pattern, federal forecasters say there’s a 75% chance of a transition to “neutral” conditions from January through March, with increasing odds of an El Niño developing later this year. We’ll see how those shifts in the tropical Pacific shape the West’s weather, but with the end of January approaching, the clock is ticking on this winter’s snowpack.

In a recent story in The Washington Post, Ben Noll and Ruby Mellen point to another possible driver of the unusual winter drought, which is also affecting parts of the South and East:

. . . a persistent marine heat wave in the North Pacific Ocean has caused the northern branch of the jet stream to blow strong and farther north, more frequently toward Alaska and occasionally toward the Pacific Northwest and California, where December brought destructive flooding events.

Marine heat waves are becoming more common and intense amid a warming climate.

For more on how this snow drought is unfolding, here are a few recent stories:

Series of big storms are needed to make up huge snow supply gap, Colorado water experts say. Shannon Mullane, The Colorado Sun, 1/21/26.

The western US is in a snow drought, raising fears for summer water supplies. Andrew Freedman, CNN, 1/9/26.

Utah’s snowpack is at a record low. Here’s what the latest water forecast shows. Brooke Larsen, The Salt Lake Tribune, 1/9/26.

Where’s the snow? For these places, there hasn’t been much this season. Ben Noll, The Washington Post, 1/8/26.

The western US is in a snow drought, and storms have been making it worse. Alejandro N. Flores, The Conversation, 1/8/26.

SnowSlang: O is for “orographic lift”

SnowSlang is my occasional look at the language of snow. More at snowslang.com.

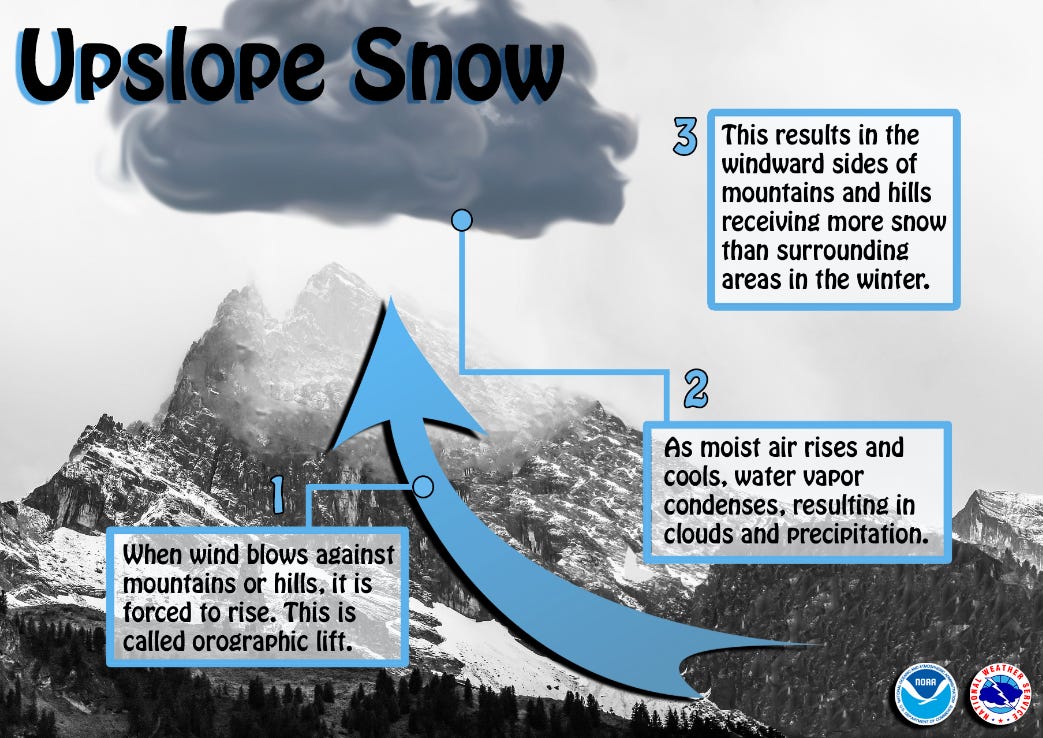

Orographic lift occurs when air is forced up over a mountain range or other elevated terrain. As the air mass rises, it expands and cools (roughly 5.5°F per 1,000 feet of elevation gain in dry conditions). Water vapor condenses into clouds, which can produce precipitation—essentially “wringing out” moisture as the air climbs.

This is why the windward sides of mountains are often wetter than the leeward slopes, where a drier “rain shadow” can form. The American West has many classic examples of the orographic effect, including the Sierra Nevada and Cascades: storms roll in from the Pacific, dump moisture on the west side, and leave areas east of the mountains parched.

Even hundreds of miles inland, wind direction plays a major role in where storms deliver the most moisture. Some ski areas do better with a southwest flow, while others are favored when storms come in from the west or northwest.

OpenSnow puts it this way:

When forecasting snow for mountains in your area, the biggest forecasting secret is to find the wind direction that favors rising air. Wind flowing freely, hitting a mountain head-on, and being forced to rise will create the heaviest snowfall.

You may also hear the term upslope snow to describe this process. Along Colorado’s Front Range, upslope storms push moisture from the Great Plains toward the mountains, where the Rockies force that air upward and can produce impressive snowfall.

Upslope storms have even inspired a Boulder-based brewery that lists “snowmelt” as one of its ingredients. Upslope Brewing Company describes an upslope storm as “a front range-covering, water-table-filling, snow-dumping weather pattern that anyone with bindings and a roof rack would die for.”

🎉 Milestone alert

snow.news just passed 750 subscribers—thanks for reading and helping spread the word. If you know someone who’d enjoy independent snow journalism, I’d be grateful if you forwarded this email to them.

Forests "choked with excess fuel" is missing the point. The issue is drought and climate change which is stressing the forests and making wildfire more dangerous. The "excess fuel" myth is promulgated by timber industry and climate deniers. Unsubscribing.