White Friday storm, snowpack update, and snow science news

The West's snowpack is off to a slow start, but it's still early in the season.

I was thrilled last week to finally enjoy my first winter storm of the season, but also reminded how snow can be a bugaboo.

The snowpack here in southwest Colorado and many other parts of the West has gotten off to a slow start—and it remains far below average in many places—so it was exciting to see the flakes fly around home.

My nine-year-old daughter wasted no time. As soon as there were a few inches of snow on the ground, she hounded me to break out the sleds. The conditions were low-tide, with lots of plants poking out, but she didn’t mind. I’ll need more of a base before I ensconce myself in the plastic saucer.

While others were indulging in Black Friday shopping, we were experiencing a White Friday as a potent storm swept across the Rockies. It snowed almost the entire day, often dumping big fat flakes and transforming our neighborhood from fall to winter mode in less than an hour.

The map below shows how much snow accumulated in Colorado (the Snow News compound is located just above the “r” in Durango, so we did quite nicely).

After Thanksgiving leftovers for dinner—and before we lost power for three hours—I went outside to reconnoiter our long driveway and was impressed/humbled to see that eight inches had already piled up in the deepest spots, so I fired up the snowblower and started doing my best impression of a Zamboni on an ice rink.

It was just as slippery on the concrete pad next to the garage, something I realized mid-air, in between my feet slipping out from under me and my butt making a cold, hard landing. Felt that one the next day.

We inherited the snowblower from the previous homeowners, who we heard moved back to Arizona because they couldn’t stand the winters at 7,600 feet in the San Juan Mountains.

As we considered buying the house in 2021, I viewed the potential for heavy snowfall as an amenity. The prospect of being surrounded by a winter wonderland with conifers weighted down with snow was a selling point.

Entering our third winter, I have no regrets about moving here, yet I now know I was a naive city slicker, and I can totally get why reasonable people would want to pack up for the sunny Sonoran Desert after living for months surrounded by snow and spending so many hours digging out.

One of the oddities of our house is that the steep metal roof over our heads will periodically let loose massive volumes of snow, similar to the dynamics of a slab avalanche, and thereby deposit enormous piles in all the wrong places.

Sometimes, after spending 20 minutes clearing a path to my front door and dutifully moving the snow that has fallen from the sky, I will helplessly watch slabs rush off the roof and refill the walkway with even more snow than I just removed. Moreover, the roof-borne slide creates a dense, compacted snowbank that’s much harder to shovel and impenetrable for the snowblower. It’s also a chilling reminder of why it can be so hard to recover avalanche victims.

The image below, from last winter, shows my daughter helping me excavate the trench.

Opening day at Purgatory: fake snow to the rescue

One week before the big White Friday storm, I headed to Purgatory for its November 18 opening. There was virtually no natural snow at Purg. A warm stretch had also limited snowmaking, so when the resort opened, it offered just a single run with artificial snow, and that intermediate trail only went halfway down the mountain.

When I was ready to head home, I had to ride the chairlift down to the base, which felt bizarre. Even so, it was a thrill to be back on skis and flying down a mountain with a gorgeous view of the San Juans before me.

Here’s a gallery of photos from the day (click images to expand):

I posted some of these photos on Reddit. As expected, the bare slopes triggered comments about climate change. “That is global warming ladies and gentlemen,” said one person.

While I wholeheartedly believe in climate change and worry deeply about its effects, it irks me when people don’t distinguish weather from climate, and when there’s too much fuss about the snowpack in November.

If we’d had a fast start to the season and the White Friday storm had happened a few weeks earlier, leaving us with above-average snowfall, that certainly wouldn’t disprove climate change, or refute that warming has already taken a toll on the West’s snowpack.

For the record, last season also featured a sluggish start for the snowpack here in southwest Colorado, but starting around Christmas, we got pounded by storm after storm and ended up with one of the deepest snowpacks in decades.

“So much global warming we got 400 inches last year,” one Reddit commenter remarked.

This notion also drives me nuts. Neither a single good year nor a bad month or two says anything about the long-term trends that really matter. It’s all just fodder for partisan rhetoric, so whenever I post a photo showing epic or awful skiing conditions, I know the imagery will serve up a Rorschach test that lets viewers project their politics and personalities.

Two days after the White Friday storm, I went back to Purg to ski with my daughter, and the mountain sure looked a lot more wintry.

Snowpack update

So how is the West’s snowpack doing? Not so hot, but we’re early in the season.

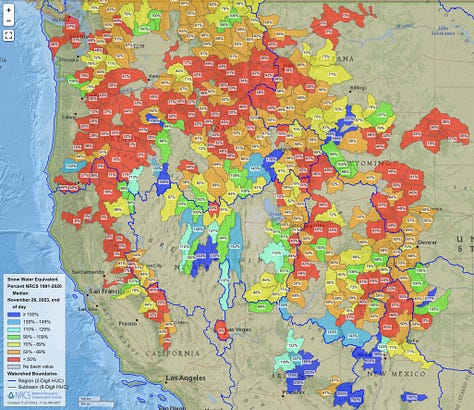

The maps below, from the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service, show how basins in the West are faring compared to the 1991-2020 median for snow water equivalent, a measure of how much water the snowpack contains. I’ve included three maps from November 26 with different levels of resolution; in all of them, the widespread red, orange, and yellow shading mean the same thing: below-normal snowpack (click images to expand).

These maps are useful for illustrating how the snowpack can vary dramatically within just a single state. But at the very start or end of the season, the basin maps can be more deceptive than instructive because they lack context and don’t incorporate the element of time. When the snowpack is just getting going or nearly gone, the numbers in these maps can bounce around wildly.

Another way to visualize the data is to use a time series. The graphic below, also from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, shows how the snow is stacking up in Utah. This season’s snowpack is illustrated with a black line, while the maximum for 1991-2020 is blue, the minimum is red, and the green line is the median.

As of November 27, the statewide snowpack was 63% of the median and in the 16th percentile, so it hasn’t exactly been a banner season. But, as the little box in the upper left notes, we still have 128 days until the median peak of the snowpack in Utah on April 3.

Snow science roundup

I’ve been keeping tabs on the latest snow science and would like to periodically share brief updates on what researchers are learning. Here are a couple of recent studies that caught my eye, along with links to the papers, press releases, and news coverage.

Less pollution expected to help the snowpack

Dust, black carbon, and other light-absorbing particles can take a toll on the snowpack by darkening the surface, reducing its albedo (a measure of reflectivity), and accelerating melting. But in coming decades, air pollution and emissions of black carbon are expected to fall with reductions in fossil fuel combustion and wood burning. So, in some good news for the snowpack, researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have concluded that less pollution will help make the Northern Hemisphere’s snowpack more resilient in the face of climate change.

“Warming temperatures and cleaner snow are competing effects,” said co-author Ruby Leung in a story from Tom Rickey at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “Our paper indicates that the warming effect is dominant, but that cleaner snow will cancel out some of the effect. We are not saying that snow will increase in the future. We’re saying that snow will not decrease in the future as much as it otherwise might.”

The paper in Nature Communications focused on the American West and the Tibetan Plateau, two regions where the snowpack plays a major role in the water supply. Snowmelt in mountainous regions provides “an important source of freshwater for more than two billion people globally,” according to the study.

Learn more

“A cleaner snow future mitigates Northern Hemisphere snowpack loss from warming.” D. Hao et al. Nature Communications, 14, 6074, October 2, 2023.

“Cleaner snow boosts future snowpack predictions.” Tom Rickey, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Phys.org, October 12, 2023.

“Cleaner snowpack could help slow climate change, provide more drinking water.” Courtney Flatt, NWNews, November 8, 2023.

Glaciers disappearing in the American West

An inventory of the West’s glaciers by Portland State University scientists concluded that some are already gone, others are no longer moving, some are too small to qualify as a glacier, and others had been misclassified.

Researchers looked at satellite and aerial data from 2013 to 2020 and identified 1,331 glaciers, 1,176 perennial snowfields, and 35 buried-ice features. A prior inventory, which was compiled over a 40-year period from the late 1940s to the 1980s, was based on U.S. Geological Survey maps.

“Glaciers are disappearing and this is a quantification of how many around us have disappeared and will probably continue to disappear,” said lead author Andrew Fountain in a news release from Portland State University. More from the release:

The new inventory excludes 52 of the 612 officially named glaciers because they are no longer glaciers . . .

The loss of glaciers impacts more than aesthetics. Glaciers act as a natural regulator of streamflow, Fountain said. They melt a lot during hot dry periods and don’t melt much during cool rainy periods. As glaciers shrink, they have less ability to buffer seasonal runoff variations and watersheds become more susceptible to drought. Retreating glaciers also leave behind sharp, steep embankments on either side, which can collapse and result in catastrophic debris flows. Globally, the loss of glaciers is also a major contributor to sea level rise.

“Researchers believe these glaciers are shrinking due to global warming – and possibly wildfires,” wrote KUNC’s Emma VandenEinde in a story about the study. “Additionally, caverns in the glacier created by streamflow underneath can let sunlight in and melt the glacier.”

The map below, from the paper in Earth System Science Data, shows the location and elevation of the West’s glaciers.

Fascinating, Mitch. You're doing really great stuff with this newsletter!