Vanishing glaciers, skiing Everest, and other snow.news

Can you guess how much the price of peak lift tickets has risen since 2000?

California’s glaciers are disappearing

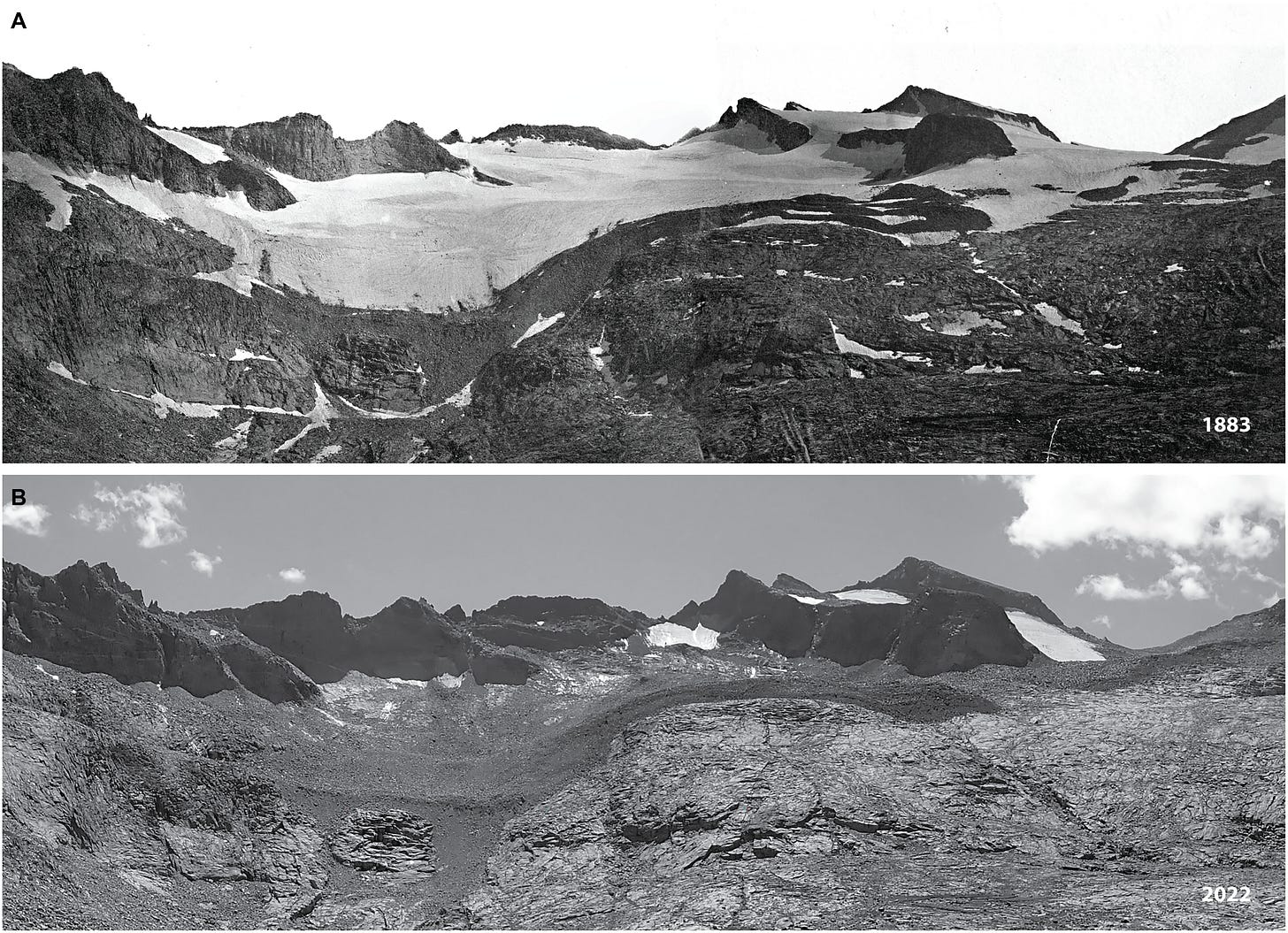

A new study offers a grim prognosis for the remaining glaciers in California’s Sierra Nevada.

Previous research suggested that the mountain range’s glaciers might have disappeared thousands of years ago, during warm spells since the end of the last ice age. But this new paper argues that a glacier-free Sierra Nevada is unprecedented in the Holocene, the current geological epoch that began about 11,700 years ago.

“Our reconstructed glacial history indicates that a future glacier-free Sierra Nevada is unprecedented in human history since known peopling of the Americas ~20,000 years ago,” the scientists write in Science Advances.

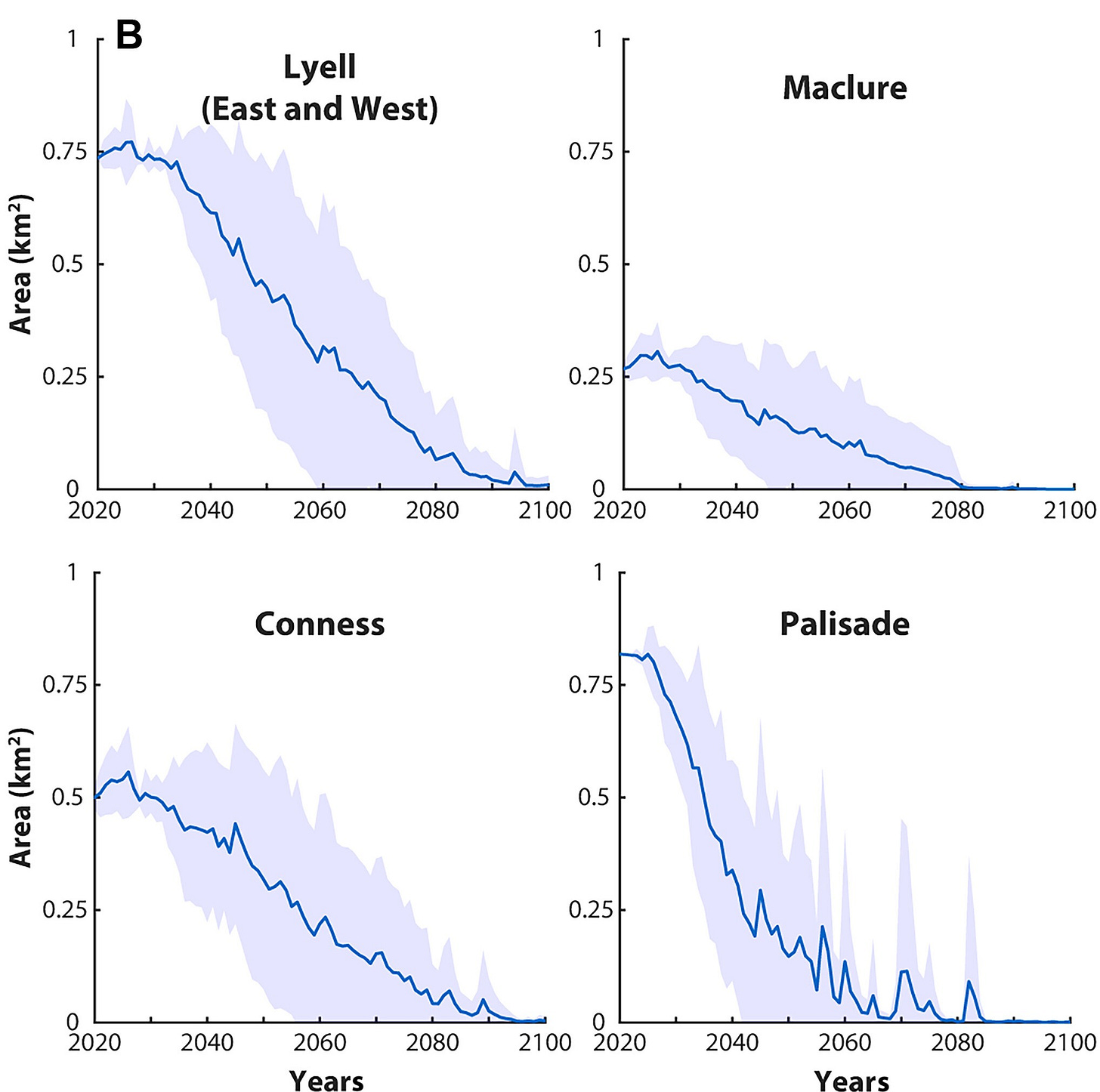

Due to human-caused climate change, summer temperatures in California have already warmed by 2° Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit) in the past century. The graphic below from the paper shows the projected trajectory of four glaciers in the Sierra Nevada.

Ian James at the Los Angeles Times has an informative story about the new study.

“It means that when these glaciers die off, we will be the first humans to see ice-free peaks in Yosemite,” lead author Andrew Jones, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, told James. “Glaciers are touchstones between the past and the present, and it’s just so visceral when you can see how it used to be and how it is today.”

James also notes that “when the snowpack is gone by late summer, the glaciers that remain, often in the shadows of peaks, release meltwater that keeps streams flowing at the driest times of year.”

If you’re hungry for more depressing news about glaciers, see this in-depth story by NPR’s Rob Schmitz about the melting in Europe and the consequences for rivers on the continent, which is warming at double the global rate.

Climbing and skiing Mount Everest—without bottled oxygen

Imagine setting off on a ski run that begins near the cruising altitude for commercial airliners. Sounds insane, but Polish athlete Andrzej Bargiel has a habit of making such death-defying descents in the Himalayas. His latest exploit: scaling 29,032-foot Mount Everest, clipping into skis, and making turns down the world’s tallest peak—all without supplementary oxygen.

Check out the video below for some footage of the unprecedented feat:

Bargiel spent nearly 16 hours climbing above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) in what’s known as Everest’s “death zone” due to the paucity of oxygen. His descent required passage through the perilous Khumbu Icefall, where he was guided by a drone flown by his brother.

“More than 6,000 people have climbed Everest, but fewer than 200 have ever done it without supplementary oxygen,” according to Red Bull, the energy drink company that sponsors Bargiel. In 2018, Bargiel made the first skiing descent of K2, the planet’s second-highest mountain—something that still hasn’t been replicated.

If you want to see some stunning photos of the expedition, check out this page from Red Bull (the images are copyrighted, so I’m not including them here). There’s more imagery on Bargiel’s Instagram page:

Rising temperatures are driving drought in the West

In my previous post, I discussed how human emissions are contributing to the megadrought in the American Southwest. It’s a one-two punch. Greenhouse gases and aerosol emissions have been altering storm tracks and reducing precipitation. At the same time, warmer temperatures are aridifying the region, drying out soils, shrinking the snowpack, and making the atmosphere thirstier.

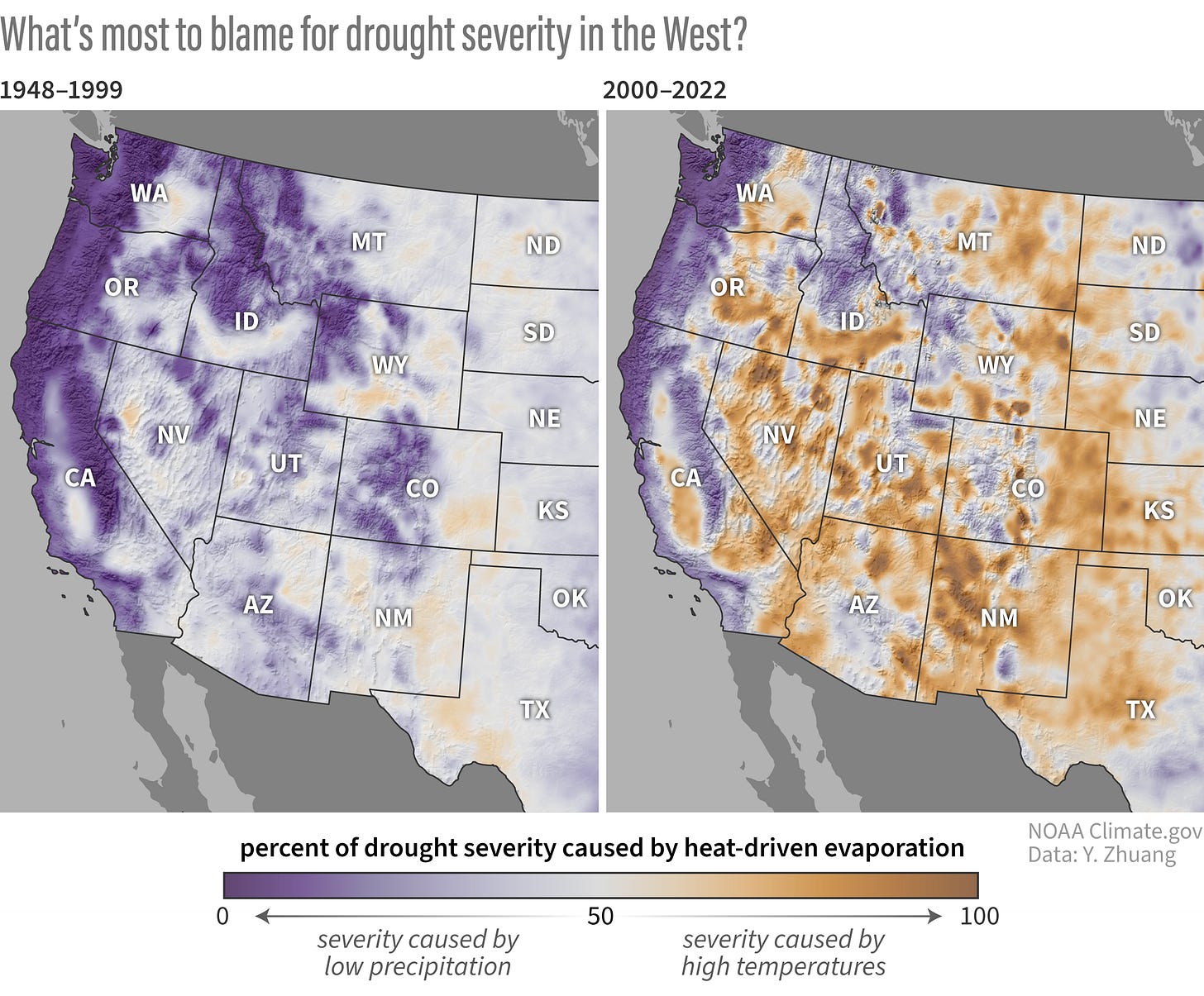

The instructive graphic below from climate.gov quantifies the impact of these two forces. From 1948 to 1999, low precipitation was to blame for the West’s drought (purple shading), but in the 2000-2022 period, greater evaporative demand driven by hotter temperatures has come to dominate in many areas (orange shading).

“The Great Plains and the inter-mountain basins and valleys have flipped from a drought regime driven mostly by precipitation to one driven strongly by drying heat,” according to Rebecca Lindsey at climate.gov. “A shift toward heat-dominated droughts means that even in years when precipitation is normal, the threat of drought remains, and it will only get worse with continued human-caused global warming.”

The data in these maps stems from a NOAA-funded 2024 study in Science Advances, titled “Anthropogenic warming has ushered in an era of temperature-dominated droughts in the western United States.” Under a high-emissions scenario, “droughts like the 2020–2022 event will transition from a one-in-more-than-a-thousand-year event in the pre-2022 period to a 1-in-60-year event by the mid-21st century and to a 1-in-6-year event by the late-21st century,” according to the study.

I came across this graphic thanks to a helpful article from David Condos at KUER. Condos interviewed Dan McEvoy, a climatologist with the Western Regional Climate Center, who was the subject of a Q&A on snow droughts that I published in June.

“If you have the same amount of water in the winter in 2025 compared to 1950, that’s not going to translate to the same amount of water into the system that you had in 1950,” McEvoy told Condos.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to the American West. Condos notes that “a recent University of Oxford study suggests that the thirsty atmosphere has increased global drought severity by 40% since the early 1900s.”

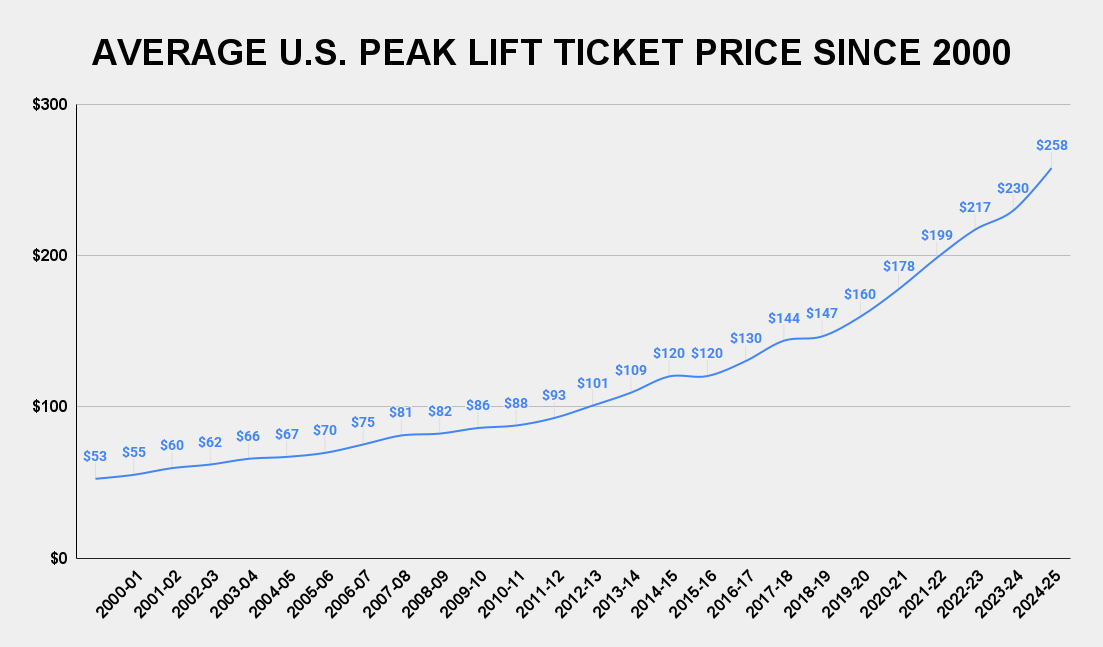

The skyrocketing cost of lift tickets at ski resorts

Skiing and snowboarding can be super expensive, especially if you don’t have a season pass and wait until the last minute to buy lift tickets. Years ago, it was news when the walk-up rate at some resorts crossed the $200 threshold; now, some ski areas are charging ticket-window rates of around $300 per day during peak periods.

Stuart Winchester, who covers ski resorts at The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast, has been tracking the numbers and recently posted the chart below showing the meteoric rise in peak lift ticket prices since 2000, using a database of 37 resorts.

The average price skyrocketed 387%, from $53 in the 2000-2021 winter to $258 in the 2024-2025 season, but much of the rise is actually due to inflation. Using the Consumer Price Index, I calculated the 2000-2001 average price to be $100 in 2025 dollars, so the increase in real terms is 158%, which is still mighty steep.

Over the past quarter-century, resort companies have shifted to selling season passes (e.g., Epic and Ikon) that cover multiple ski areas. The outrageous rates for single-day tickets have motivated many skiers and snowboarders to buy the passes, which can now top $1,000 per season. If you slide on snow frequently, these passes can be a good deal, but when you add in the costs for travel, lodging, equipment, and food/beverages, it’s hard to avoid shelling out big bucks to hit the slopes.

Skiing and snowboarding are pricey, but as I like to say, they’re cheaper than therapy and potentially just as effective.

Bye-bye, basin snowpack maps?

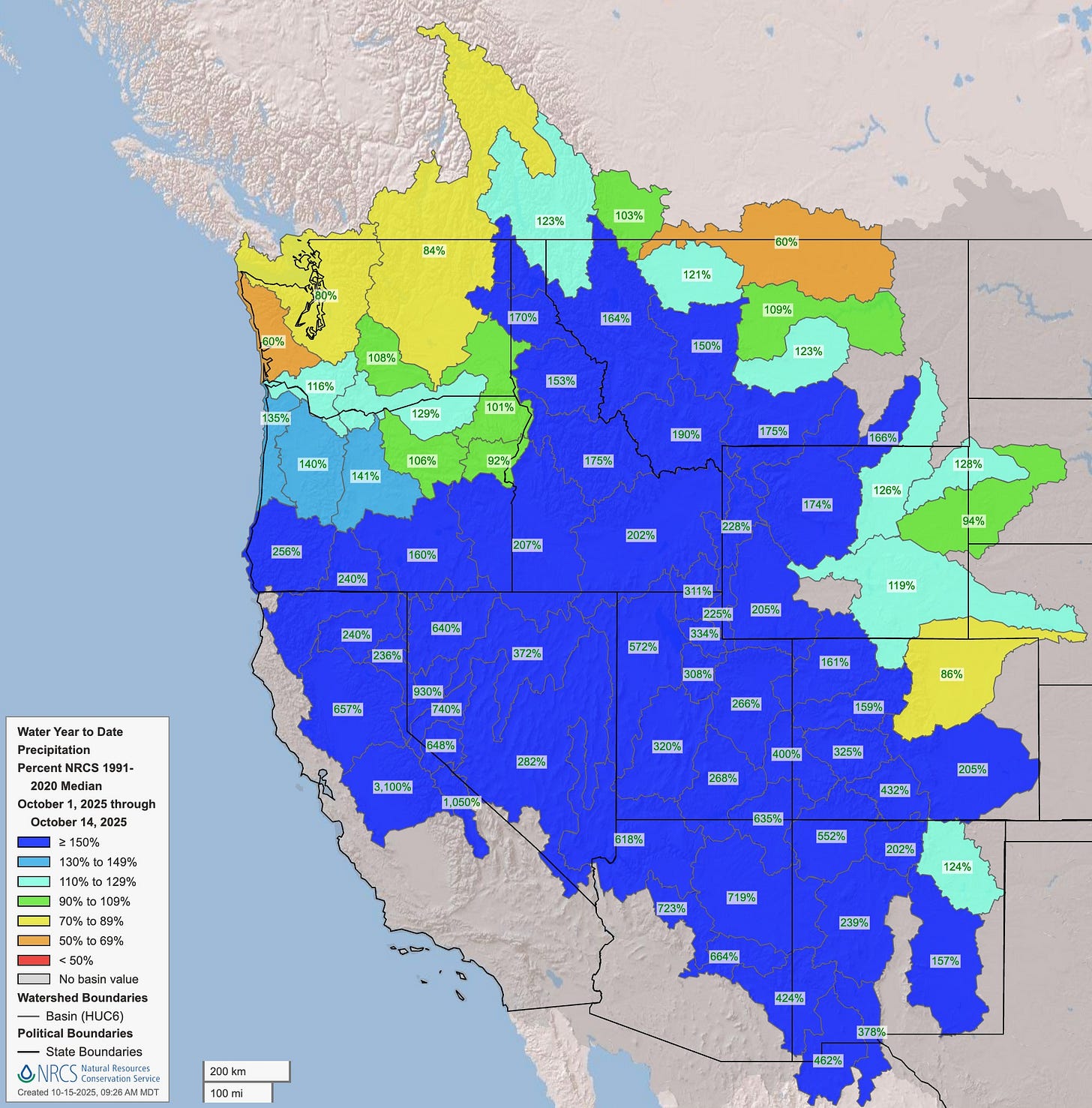

During the snowpack season, I have regularly consulted this site run by the Natural Resources Conservation Service to download and share maps showing how snow is stacking up in river basins across the West.

Alas, the federal government has decided to retire these maps, and during the ongoing shutdown, it has added this cheeky proclamation:

Snowpack data are also usually available on the NRCS iMap interactive, which includes readings from individual SNOTEL stations and streamflow information. Unfortunately, only some of the basins are now reporting snow water equivalent.

The map below, which shows total precipitation in each watershed, indicates that the West’s water year has started wet, but in many places this moisture has fallen as rain rather than snow. Some of these percentages are enormous because the historical median is very low at the beginning of the season.

Here in southwest Colorado, the past week has been incredibly wet, thanks to remnants of two tropical systems from the Pacific. My weather station has recorded more than six inches of rain since October 9, but the actual total is even higher—it was so stormy that my rain gauge went offline for a while! The tropical origin of the storms means they’ve come in warm, so only the highest peaks around here have received snow.

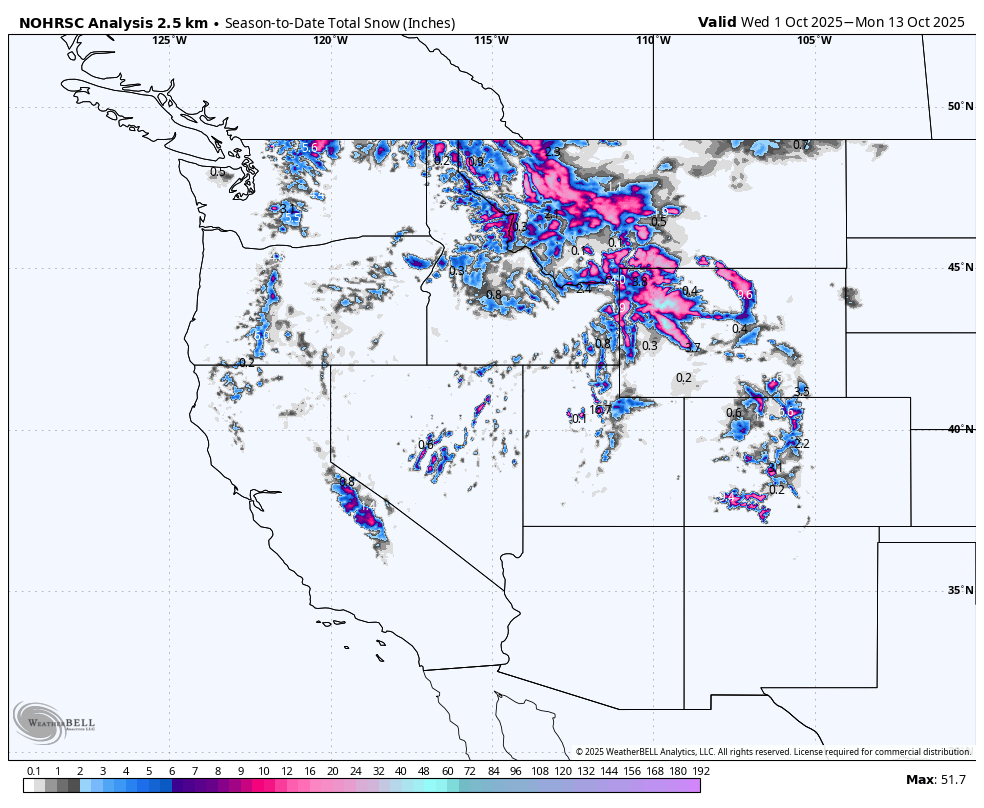

The map below shows total snowfall in the West from October 1 to 13.