Summer snow.news roundup

Plus SnowSlang: K is for "krummholz"

It’s been hot, dry, and smoky for much of the summer here in Southwest Colorado. Snow has felt a world away, but the days are shortening, the nights are cooling, and it hopefully won’t be too long before the first flakes are falling on the highest peaks.

In the meantime, I’ve been taking some mental retreats from the vernal heat by delving into snow-related stories and studies, some of which I summarize below . . .

📏 Bill would boost monitoring of the West’s snowpack

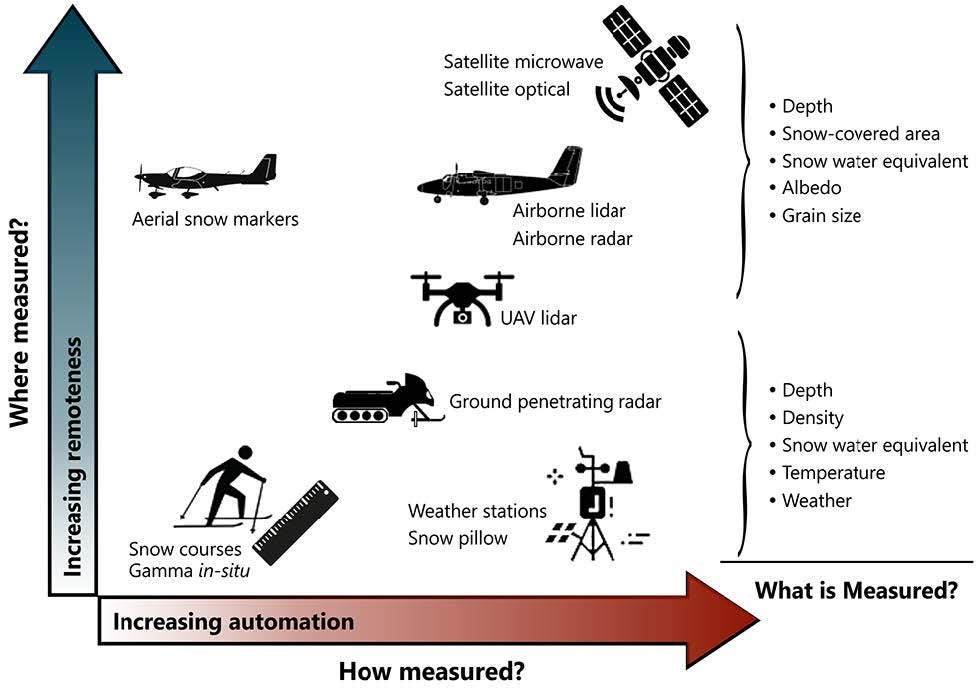

A bipartisan bill introduced by Colorado Sen. John Hickenlooper (D) and Utah Sen. John Curtis (R) aims to improve the federal government’s monitoring of the West’s snowpack. The Snow Water Supply Forecasting Program Reauthorization Act of 2025 would reauthorize and boost funding for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Snow Water Supply Forecasting Program through 2031. “You can’t manage what you can’t measure,” Hickenlooper said in a press release. “Snowmelt is Colorado’s largest reservoir. Leveraging advanced snow monitoring tech will give us more accurate water predictions and unlock a better understanding of how to make the most of our water in an era of extreme drought.”

For more on the legislation, see this story from Shannon Mullane at The Colorado Sun.

☹️ New research finds human influence on Southwest’s drought

The Southwest’s ongoing megadrought has been caused partly by rising temperatures that are drying out soils, making the atmosphere thirstier, and extending the growing season. Another factor has been declining precipitation, yet it has been challenging for scientists to attribute that change to greenhouse gases and other human-caused emissions, rather than chalk it up to natural variability in a region given to feast-or-famine precipitation.

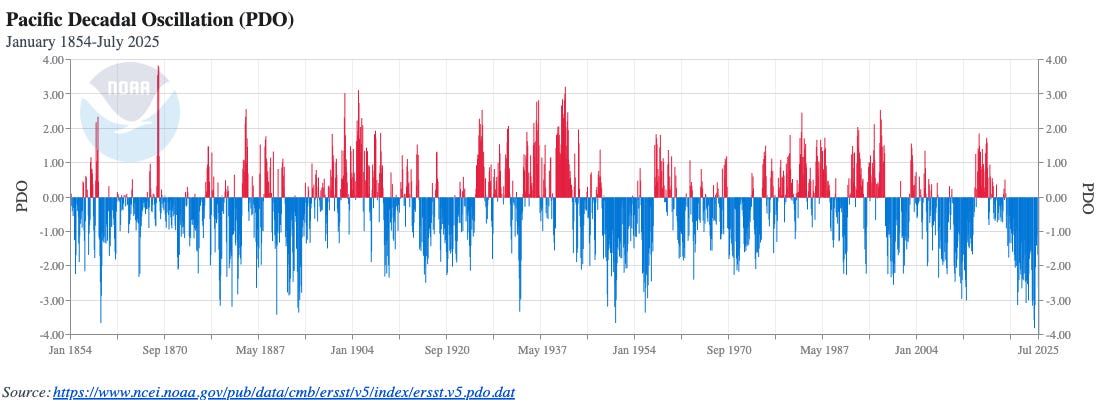

But a trio of new studies published this summer has identified our air pollution as a major cause of the drying conditions in the Southwest, particularly through its effects on a pattern known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which recently hit a record low, as shown in the graphic below. Moreover, the impacts are expected to persist in the coming decades due to ongoing carbon emissions and warming.

You can find the papers here, here, and here. Bob Henson has a good roundup of the studies at Yale Climate Connections:

Climate change appears to have driven an ongoing 25-year shortfall in winter rains and mountain snows across the U.S. Southwest, worsening a regional water crisis that’s also related to hotter temperatures and growing demand. Multiple studies now suggest that human-caused climate change is boosting an atmospheric pattern in the North Pacific that favors unusually low winter precipitation across the Southwest . . .

. . . Even more disconcerting is what the new work suggests for the Southwest going forward. The Nature study warns that as long as human-produced greenhouse gases and aerosols continue to produce these effects, “the PDO will remain persistent in its negative state, driving continued precipitation deficits in the western U.S.”

I’m working on a longer piece about the recent research that I’ll share down the line. My interesting conversations with some of the authors have given me a new appreciation for the importance of the PDO, which is typically overshadowed by El Niño and La Niña . . .

¿La Niña again this winter?

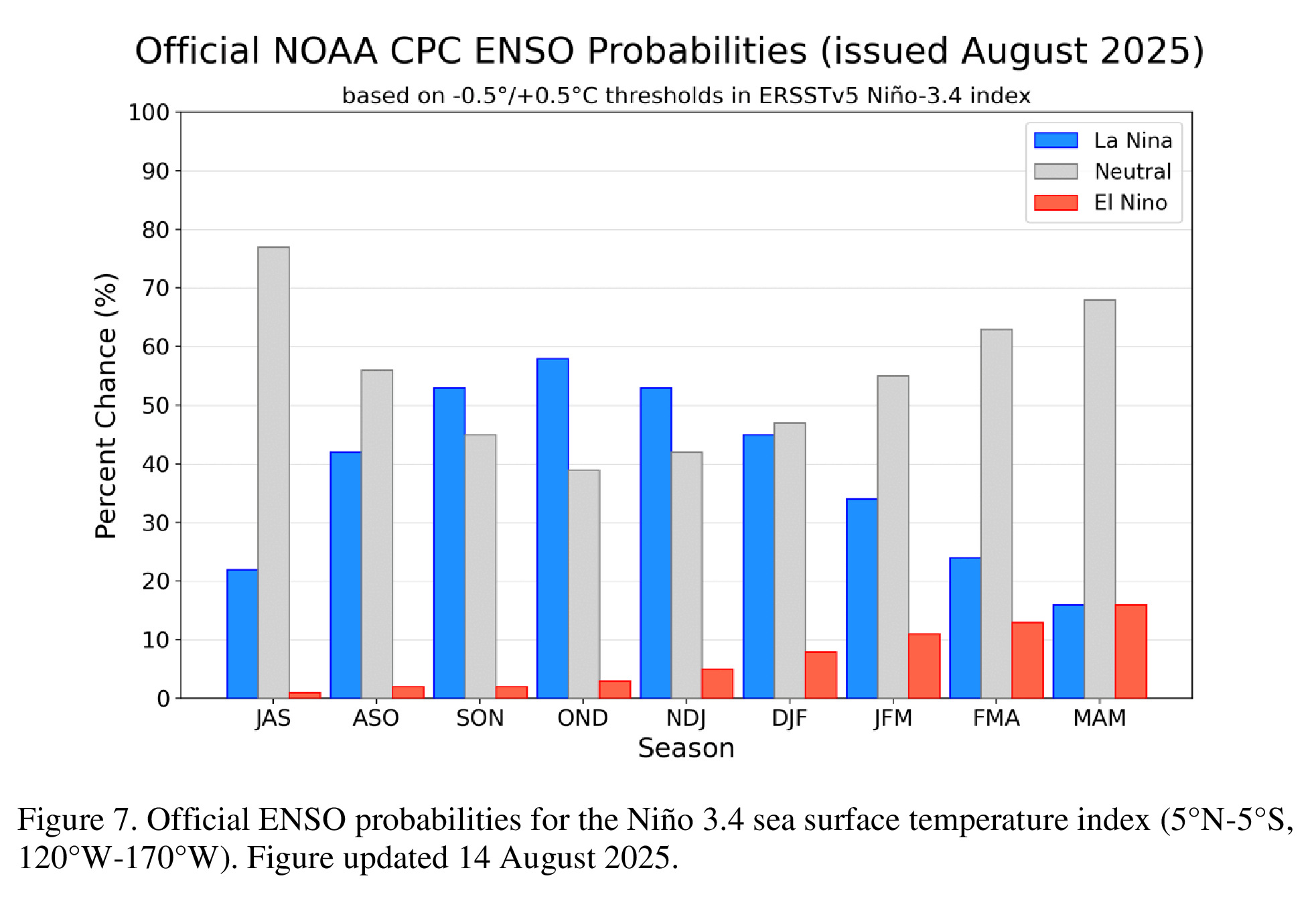

An August 14 update from the Climate Prediction Center highlights the possibility of another La Niña making an appearance this winter. But a lot is still up in the air, and down on the sea surface of the tropical Pacific. In the graphic below, the blue bars show the chances of La Niña during rolling three-month periods. Odds of an El Niño (red) are very low. We’re currently experiencing neutral conditions (grey), which is jokingly referred to as La Nada.

It’ll be interesting to see what happens in the Pacific in the months ahead. La Niña tends to bring drier weather to the Southwest and other states in the south, with wetter conditions more likely across the Pacific Northwest. But that’s just one piece of the puzzle and by no means a guarantee. As noted above, other patterns in the Pacific, such as the PDO and its connection to the Aleutian Low, also influence the West’s weather.

We’re now under a La Niña Watch, but the odds of neutrality are expected to rise during the winter: no need yet to check on the pets or hug your kids extra tight.

Here’s what The Washington Post’s Matthew Cappucci and Ben Noll have to say about the potential impact this winter:

La Niña winters tend to feature a wavy and variable polar jet stream. The cooler Pacific waters and sinking air generate high pressure in the eastern and northeast Pacific, which in turn shunts the jet stream north toward the Gulf of Alaska. Then it dives southeast over the northern half of the Lower 48.

That pulls moisture ashore in the Pacific Northwest, leading to wetter conditions. Extra-cold air spills across the north-central U.S., where the jet stream dips.

Across the southern U.S., warmer, drier weather usually prevails . . .

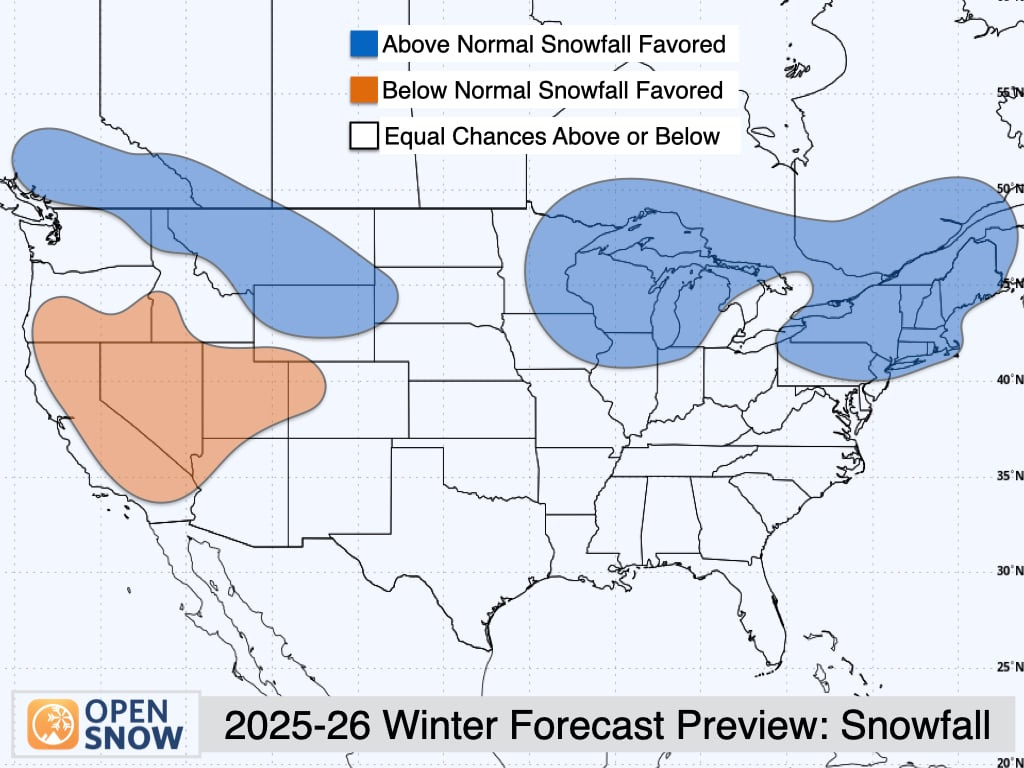

We’re still in August, but that hasn’t stopped folks from already laying down their predictions about what the coming winter will look like. As I’ve written over and over, you should take such prognostications with a chunk of road salt because our current ability to predict the weather many months in advance is little more than an educated guess.

One of the best sources for tracking wintry weather is OpenSnow, which I follow closely during the season—and during the summer for the wildfire smoke maps! Its winter forecast has an interesting discussion of analogous years with weak La Niña conditions. Here’s a map summing up OpenSnow’s outlook:

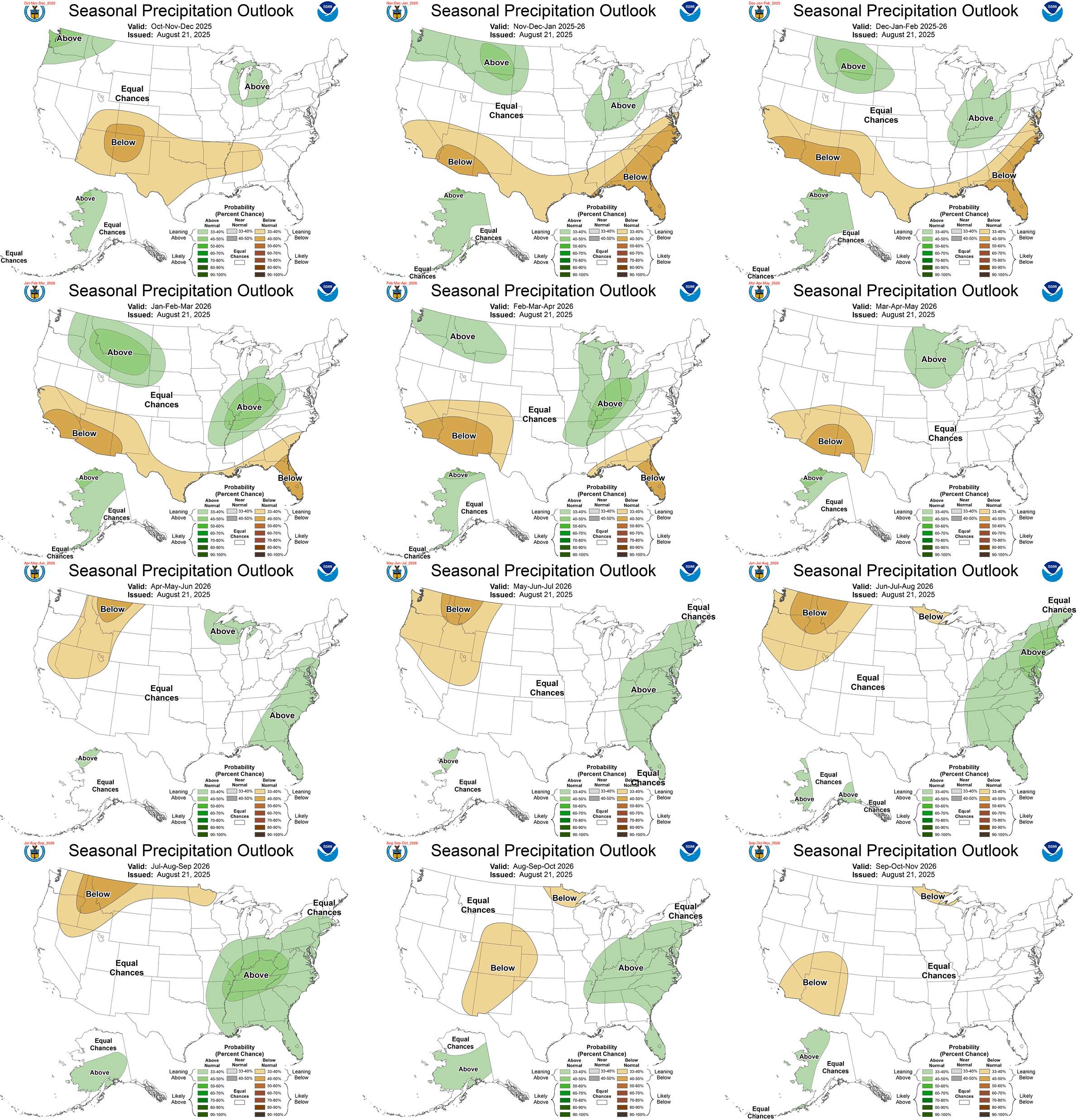

The maps below show the Climate Prediction Center’s rolling three-month seasonal outlooks for precipitation, with some indication of wetter conditions in the Northern Rockies this winter.

And let’s not forget to make fun of the Farmers’ Almanac! As I’ve noted before, these publications are more like astrology than meteorology. In this year’s edition, the Farmers’ Almanac is calling for “wet, “snowy,” and “snow-filled” conditions across the entire country, from coast to coast. I hope they’re right, but I wouldn’t bet the farm!

🌲 Forest carbon storage suffers from shrunken snowpack

A July paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports some disturbing news about the effects of reduced snowpack on carbon sequestration in forests.

Temperate forests in the Northeast now act as “carbon sinks” that help offset humans’ greenhouse gas emissions by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Warming temperatures are supposed to increase carbon storage in forests by boosting photosynthesis. But those higher temperatures are also hurting the snowpack and exposing the forest soils to more freeze/thaw cycles, which damages tree roots, reduces nutrient uptake, and slashes the capacity of the forest to store carbon.

A decade-long experiment in New Hampshire’s Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest led researchers to conclude that current models are significantly overestimating the role of temperate forests in sequestering carbon and offsetting human-caused climate change.

For more on the carbon storage study, see this piece in The Hill by Sharon Udasin.

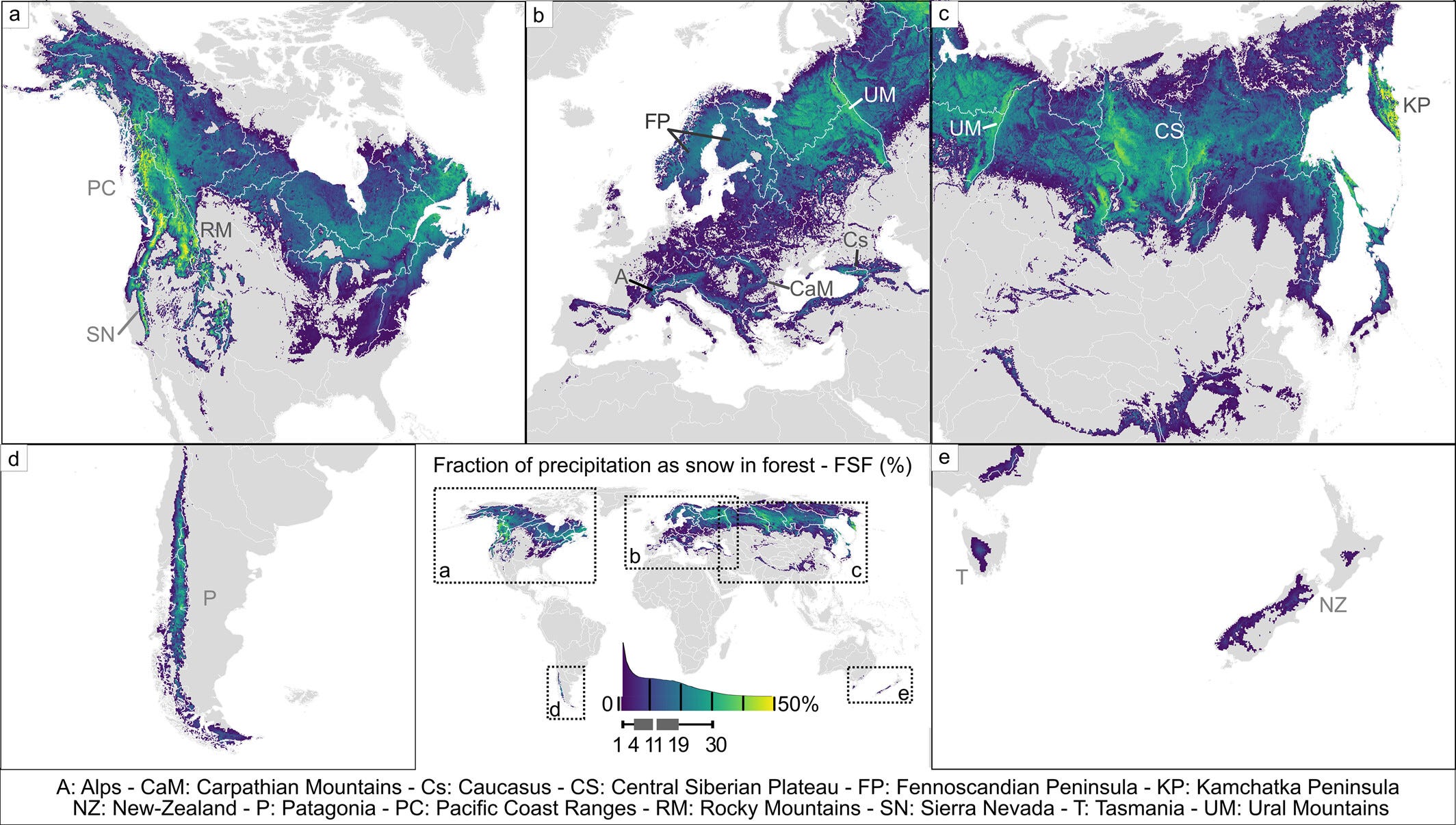

And if you’re wondering about where snow and forests meet, another recent study in Geophysical Research Letters has produced an atlas of the interactions. The map below from the paper shows the fraction of precipitation falling as snow on forests. Overall, about 23% of the planet’s land mass experiences snowfall in forested areas, mostly in the boreal forests at higher latitudes.

⚠️ Juneau’s Glacial Lake Outburst Flood

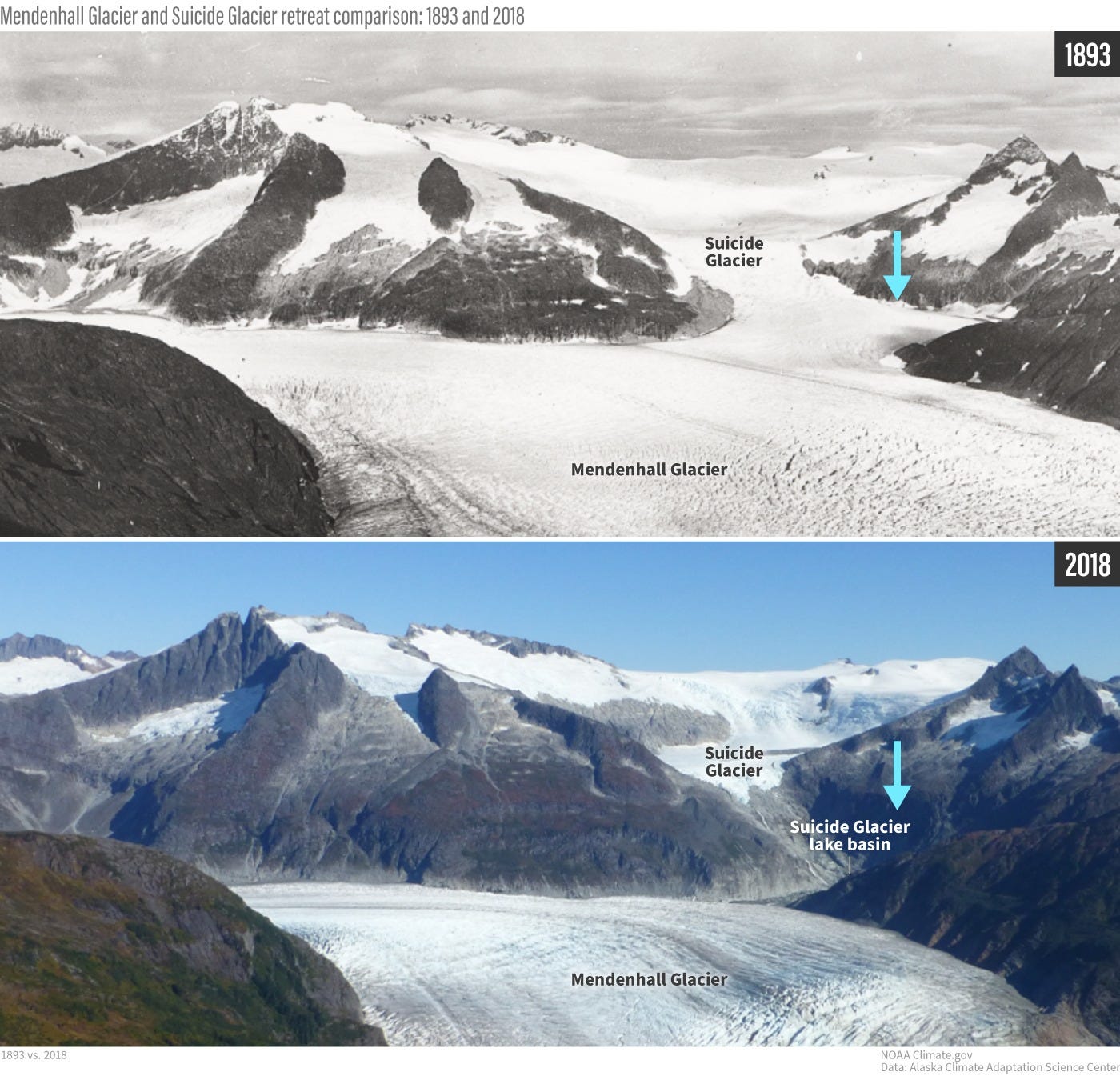

In a recent SnowSlang post, I wrote about the jökulhlaup, a type of flood emanating from glaciers that’s pronounced “yo-KOOL-lahp.” As you may have seen in the news, just such a destructive event struck Juneau, Alaska, earlier this month.

As noted in this piece on climate.gov, the flooding is “not possible without climate change.”

If you’d like to learn more about the Suicide Basin outburst floods and see some very cool data visualizations, please check out this excellent story map from the Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center.

The repeat photography below, which shows images from 1893 and 2018, lays bare the striking changes in the landscape as the Mendenhall and Suicide glaciers have retreated in a warming world.

📖 SnowSlang: K is for “krummholz”

Treeline is one of my favorite places to ski. There’s something magical about that progression from barren tundra to the widely spaced trees at the start of the forest. If you spend time in these high-elevation transition zones, you’re likely to see small trees/bushes that take on strange, warped shapes. Welcome to krummholz, which Merriam-Webster defines as a “stunted forest characteristic of timberline.”

The word’s etymology is German: krumm means “crooked, bent, twisted” and holz means “wood,” according to Wikipedia, which also notes that an alternate word, knieholz (“knee timber”), is used to describe the diminutive vegetation.

These tenacious trees have been reduced to shrubs by the harsh environment in which they live. Throughout the year, strong winds rake the mountainsides, inhibiting vertical growth and easily breaking branches. Some trees are so affected by the wind that they only grow branches on their leeward side, leading to the creation of “banner” or “flag” trees (similar formations are seen in places like the Oregon coast).

Krummholz must contend with frigid temperatures and a very short growing season, which also keeps the vegetation’s height in check. Poor soils and intense UV radiation can inhibit growth. And during the winter, snow loads can easily damage the trees and prevent them from growing tall.

Over the eons, krummholz trees have evolved an effective survival strategy to persist in places where you and I would quickly perish from exposure to the elements. These dwarf forests may not evoke the majesty of the lofty redwoods, but they still provide essential habitat for wildlife and are enchanting in their own right.