Snow and warfare: 1776-2026, Part 1

Wintry weather has confounded warriors for ages, and the cryosphere lies at the crux of some of recent history's most consequential battles.

In an earlier post, I outlined 10 reasons why snow is so important, including its impact on the water supply, biodiversity, farming, wildfires, winter sports, and the climate.

That list focused on snow as a beneficial resource that generates value—natural, economic, recreational, and aesthetic. These magical ice crystals can even make us feel warm and fuzzy.

Something I failed to cover: snow’s long-standing role as a mortal threat, terrifying obstacle, and destroyer of lives, especially in the realms of transportation and warfare.

As an inveterate worrier prone to catastrophizing and covering the doom-and-gloom beat, I sincerely regret the omission!

In this post—the first of a two-part series—I focus on warfare and begin to survey key armed conflicts in which snow and wintry weather have been pivotal. I’ll publish Part 2 soon.

Taking the long view, snow, ice, and frigid temperatures have played a leading role in military history because they have sometimes created insurmountable threats and barriers for manpower and material while setting the terms for key battles whose outcomes still resonate in today’s precarious balance of power.

The calendar says 2025, yet to me it feels a little like 1914 or 1939, as rivals clash, alliances crumble, citizens radicalize, climate change intensifies, economic inequalities widen, and digital technologies create a flood of disinformation.

Pardon me if this subject seems like a dark departure for an outdoorsy science writer and multimedia journalist fond of bluebird powder days, but I was once an aspiring nuclear strategist! This was during my hawkish teenage years in the 1980s at the height of the Cold War (more on that in Part 2).

I remain captivated by military history, one of the genres I read in my leisure. It’s also a subject that’s increasingly relevant in today’s dangerous, volatile world as the hegemony of the United States melts and the nation faces mounting—and compounding—threats from China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, non-state actors, homegrown terrorists, extreme weather, and more.

While my primary interest in snow revolves around things like skiing and streamflows, I’m casting a broad net here at snow.news, and I know I can’t tell the story of snow without exploring the morbid and tragic angles.

As we’ve seen in Ukraine, winter weather remains a part of current warfare. Although snow wasn’t an issue when the United States fought in Vietnam and Iraq, our nation’s longest war in Afghanistan featured a “fighting season” largely dictated by snow cover.

Looking ahead, the rapidly changing cryosphere is a key military issue in the 21st century. “Arctic Heating Up Literally and as Scene of Strategic Competition” is how the U.S. Department of Defense titled an April 2023 piece.

Or see this August 2025 story in The Wall Street Journal, titled “Very Cold War,” about preparations for a “subzero battlefield” in the increasingly contested Arctic.

Below are the first 6 of 13 examples from military history in which snow, ice, and winter weather were defining features.

This mile-wide and inch-deep approach scratches the surface. If you’d like to learn more about these episodes, I’ve listed resources for further reading; some of the books are still on my docket, but anything marked with a ✅ means I’ve read the source and recommend it.

I’ve been toying with the idea of writing a book about snow someday, and if I ever take the plunge, a major chapter will focus on winter warfare. In this series, I’m reconnoitering the terrain. Don’t hold your breath for the book: I may need to wait until my retirement, given that my first book—Endangered: Biodiversity on the Brink—entailed slaving away for years in exchange for a pittance.

1) Battle of Trenton and Valley Forge winter in the Revolutionary War

On the night of December 25/26, 1776, General George Washington led his troops across the icy Delaware River in a daring winter maneuver and ensuing battle during the fledgling nation’s fight for independence. Months after the Declaration of Independence, the fate of the colonies was precarious, and the future of the young republic was in doubt.

We’re preparing to celebrate the nation’s Semiquincentennial (250th anniversary) of the 1776 American Revolution, so it’s easy to associate that year with celebration and triumph. Yet from a military perspective, 1776 was filled with crushing defeats for the Continental Army, most notably the British rout in the Battle of Long Island, which led to the loss of New York City and a grueling retreat across New Jersey.

As 1776 drew to a close, morale among the revolutionary troops was dismal. Supplies were scarce, enlistments were expiring, and many wondered if the Continental Army could survive the winter. But Washington decided to gamble and led the famous charge across the Delaware, surprising the Hessian troops at Trenton, New Jersey. The Hessians—German soldiers hired by the British—didn’t expect their foes to strike during such inclement conditions.

The weather at the time was a classic nor’easter storm that pelted the soldiers with snow and sleet. Incredibly, some of the troops made the crossing without any boots and wrapped rags around their feet to prevent frostbite, or at least tried to.

Washington’s victory in the Battle of Trenton helped turn the war around. Soon thereafter, Washington succeeded again in the Battle of Princeton, further boosting the esprit de corps and helping improve enlistments in the army.

There was still a lot of fighting ahead. After the British captured Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, Washington’s army set up a winter camp in Valley Forge, about 20 miles northwest of the city, where they faced frigid conditions marked by deprivation and disease. Some 2,000 of the 12,000 troops perished before spring. But the Continental Army somehow endured that brutal winter and, with support from the French, would slowly gain control of the war, which ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

📖 Learn more:

✅ Washington's Crossing, David Hackett Fischer, 2004.

2) Napoleon’s Russian Campaign of 1812

Things didn’t go so hot for Napoleon when he tried to invade Russia in 1812. France’s supreme military commander set out to punish Russia because Tsar Alexander I wasn’t participating in an economic blockade against Britain, France’s main rival. Napoleon envisioned a quick victory to bring the Russians back into the fold and secure France’s dominance in Europe, but that proved to be a fool’s errand.

In June 1812, Napoleon led his Grande Armée, comprising more than 600,000 soldiers, into Russia. Rather than directly confronting the invaders, the Russians steadily retreated while burning crops, villages, and supplies in their wake in a scorched-earth campaign on their own turf. The Russian strategy strained Napoleon’s supply lines, but the French eventually reached Moscow—only to find that much of the city had already been burned to the ground.

Napoleon hoped to negotiate a peace with the Tsar, but with no agreement in sight, the Grande Armée began a tardy retreat in October, exposing it to increasingly dire weather conditions. Soon, the ill-prepared soldiers were facing frostbite and hypothermia as their horses were freezing to death. Starvation stalked the retreating army, with some units reportedly turning to cannibalism to survive.

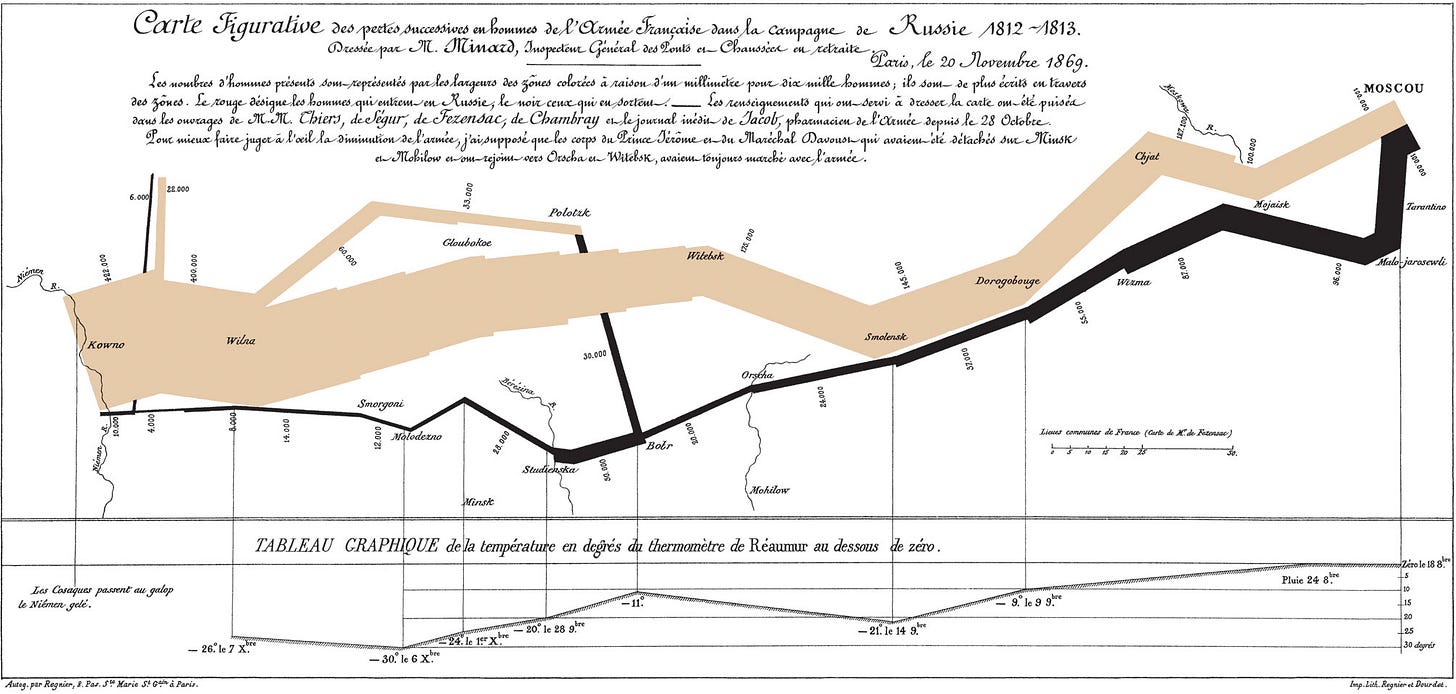

Historians would eventually highlight the role of “General Winter” or “General Frost” in precipitating the disaster, but it turns out that most of the casualties occurred long before the onset of cold weather due to factors such as disease and hunger. You can see that in the famous graphic below by Charles Joseph Minard, a French civil engineer who charted the army’s size during the advance (beige) and the retreat (black) while also plotting the temperatures they faced on the way home.

Data visualization guru Edward Tufte, whose undergraduate political science class more than 30 years ago sparked my interest in data analysis, called this flow map “probably the best statistical graphic ever drawn.”

It wasn’t only the weather that doomed Napoleon’s troops. But by staying too long in Moscow, Napoleon left his soldiers vulnerable to the Russian winter, offering a lesson that Adolf Hitler would ignore more than a century later.

📖 Learn more:

Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March, Adam Zamoyski, 2005.

3)The 1854 Battle of Balaclava

I view the balaclava as must-have gear for skiing and snowboarding in cold weather. I just wish the name of the garment didn’t constantly remind me of baklava, that scrumptious Greek dessert with honey and phyllo dough!

The name of the accessory is rooted in a famous fight during the Crimean War (1853-1856) that became known as the Battle of Balaclava. During this episode of European warfare, Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire were fighting against Russia. The battle on the Black Sea coast of Crimea was the site of a disastrous cavalry charge by the British straight into the Russians’ artillery fire that was immortalized in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”

Although the battle took place in October, the weather was cold enough that soldiers’ families and supporters back home knitted special garments to keep the warriors’ heads warm.

In his Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper writes that the clothing was initially called a Balaclava helmet. The term doesn’t appear before 1881 and “seems to have come into widespread use in the Boer War,” when British troops once again faced bitter cold, according to Harper.

📖 Learn more:

24 Hours at Balaclava, Robert Kershaw, 2019.

4) The White War in the Italian Alps: 1915–1918

World War I conjures images of trench warfare in the muddy lowlands of Europe, but part of the conflict was waged high in the mountains as Italy and Austria-Hungary fought for control of the Alps and Dolomites.

In an extreme alpine environment, the soldiers faced blizzards, brutal temperatures, and dozens of feet of snow in what became known as “The White War.” Some of the fighting transpired at elevations above 10,000 feet. Historians have noted that roughly two-thirds of the dead fell prey to the elements, such as avalanches, frostbite, and exposure, and only one-third perished due to the fighting itself.

Like much of the rest of World War I, the Italian campaign was marked by outrageous death tolls and casualties that were incurred in exchange for tiny territorial gains. Not only were trenches cut into the mountains, but soldiers were also ensconced in ice caves. Tunnels were bored into glaciers.

Avalanches took an almost inconceivable toll on the armies, with some estimates of the fatalities in the tens of thousands. In one notable incident, known as the “White Friday” disaster, avalanches possibly triggered by artillery fire may have killed 2,000 people in a single day.

📖 Learn more:

The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919, Mark Thompson, 2009.

✅ “The Most Treacherous Battle of World War I Took Place in the Italian Mountains,” Brian Mockenhaupt, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2016.

✅ “A Century Later, Relics Emerge From a War Frozen in Time,” Michele Gravino, National Geographic, October 18, 2014.

5) The Winter War: Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939

At the start of World War II, the Soviets were nervous about their northwestern border. In response, Moscow pressured Finland to cede territory so it could secure a naval base and push the frontier back from the vulnerable city of Leningrad. The Finns’ resistance prompted nearly half a million of Joseph Stalin’s troops to invade on November 30, 1939, beginning what became known as “The Winter War.”

Outnumbered, the Finnish troops were able to check the Soviet advances due to their better preparations for winter warfare, including proper camouflage and their reliance on the “Motti” strategy, in which ski troops would divide and conquer Soviet columns in snowy forests.

In the end, the Soviets prevailed over Finland, which ceded around one-tenth of its territory, but the nation retained its independence. Although the war was a defeat for Finland, Soviet casualties were far higher, and the weaknesses in the Red Army were exposed, helping inspire Hitler to eventually break his alliance with Moscow and attack the Soviet Union.

📖 Learn more:

White Death: Russia's War on Finland 1939–40, Robert Edwards, 2006.

6) Nazis and nukes: Norwegian heavy-water sabotage

What if Hitler got the bomb? A terrifying thought, and it could have happened. Were it not for a daring operation in the snowy mountains of Norway, the world might have eventually faced a nuclear-armed Third Reich, though historians still debate how close the Germans came to this nightmare scenario.

During World War II, German scientists were trying to build an atomic bomb, just like their counterparts in the Manhattan Project in the United States. The German strategy hinged on developing a supply of “heavy water,” a form of H2O in which the hydrogen atoms are the isotope deuterium. This heavy water could be used in a nuclear reactor to sustain a chain reaction that converts natural uranium into plutonium-239. The Germans had uranium, but they lacked the means to enrich it, so heavy water offered a way to create fissile plutonium that could be used in weapons.

The Germans were busy producing heavy water at Vemork, a hydroelectric plant located in a gorge in the Telemark region of Norway, so the facility became a prime target. First, a 1942 British glider assault ended in disaster. Then, in a 1943 commando raid that would later be immortalized in books and movies, Norwegian resistance fighters used skis to reach the plant in harsh winter conditions and blow up the heavy-water cells.

The Germans tried to restart operations and ship the remaining heavy water to the motherland, but once again, saboteurs struck and sank the ferry that was transporting the valuable cargo, killing some Norwegian civilians in the process.

📖 Learn more:

✅ The Winter Fortress: The Epic Mission to Sabotage Hitler's Atomic Bomb, Neal Bascomb, 2017.

Assault in Norway: Sabotaging the Nazi Nuclear Program, Thomas Gallagher, 2010.

Stay tuned for Part 2 . . .

In the second half of this series, I cover other conflicts in which snow and winter weather figured prominently. I also write about the Arctic's growing strategic importance as the cryosphere is transformed by climate change.

And, sadly, I look ahead to the not-so-distant future, when geopolitical instability could spiral out of control and lead to a nuclear winter that threatens billions of lives and plunges the planet into a cold, dark era that resembles a mini ice age . . .