Fun powder days amid grim climate projections

Skiing toward a "snow-loss cliff" as parts of the West begin to climb out of a snow drought

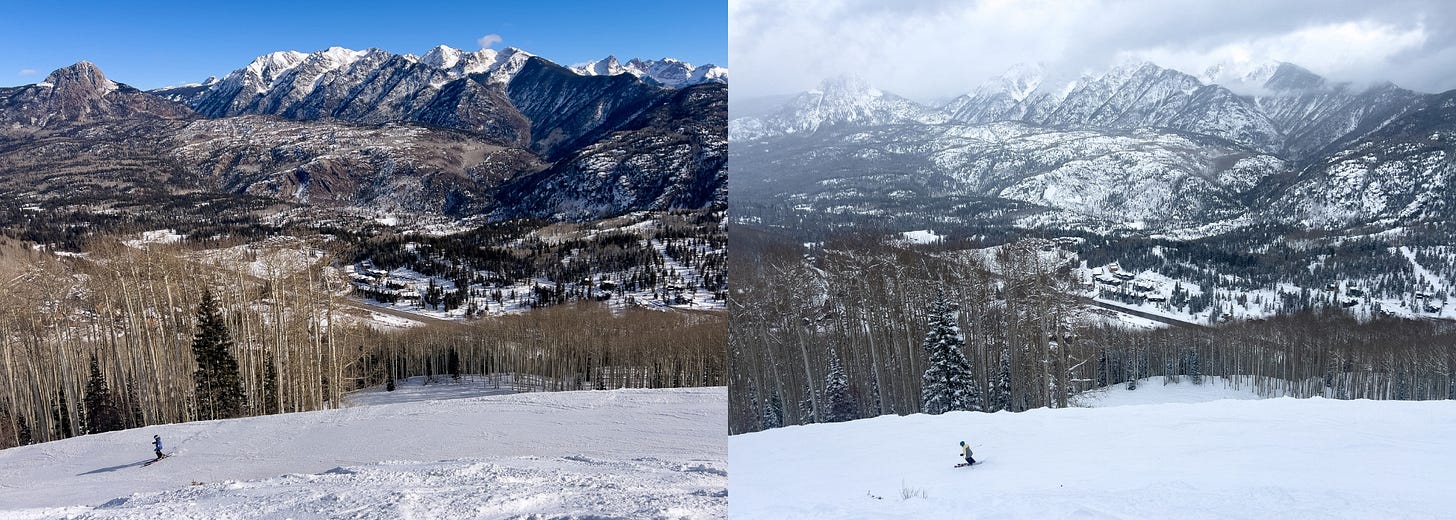

Footage from recent powder days at Purgatory in southwest Colorado. Video by Mitch Tobin.

I’ve enjoyed some fun powder days the past two Sundays. They were especially sweet after the lousy start for our snowpack and workdays filled with dispiriting projections about climate change.

Below, I briefly discuss three recent scientific inquiries that cover snow and climate, at least in part: a peer-reviewed study about the Northern Hemisphere, a U.S. synthesis of research, and a Colorado-specific report. All of these publications explain why a warming planet spells trouble for the snowpack.

But before we swallow those bitter pills, let’s talk powder! Although I dread musicals, I do believe in the advice from Mary Poppins: a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down.

For me, a powder day is an antidote to burnout, pessimism, and climate anxiety. It’s escapism, pure and simple, and a welcome respite from staring at a screen. It’s also a potent, personalized reminder of what’s at stake, which serves as a motivator for me amid the doom and gloom that suffuses environmental journalism and our sour national mood.

Judging by all the hoots and hollers at Purgatory, I wasn’t the only one desperate for some fresh snow. After a warm, dry start to winter, many parts of the West were recently pummeled by strong storms, as shown in the snowfall map below from January 10 through January 14. In some areas, accumulations were measured in feet.

My nine-year-old daughter is a little shredder and enrolled in an all-day ski program at Purgatory on Sundays, so I’ve been logging some epic sessions. On Monday mornings, my 53-year-old body has felt like it was run over by a snowcat, but the soreness and pre-dawn weekend wake-ups have been worth it.

One of my favorite things about skiing and snowboarding doesn’t involve sliding on snow—it’s capturing photos and videos in a gorgeous setting with no shortage of adrenaline junkies showing off for their buddies and chairlift paparazzi like me. “Kodak courage” is what they called it back in the days of film.

I was an early adopter of GoPro cameras and have become fascinated with their 360-degree model, which has ultra-wide-angle lenses on the front and back that let you record in all directions simultaneously.

I typically frown on selfies but make an exception when I sport an ice beard or when I can film myself skiing, snowboarding, or biking using an “invisible selfie stick” that makes it look like the camera is floating next to me, as shown in the video below.

I’m still trying to wrap my mind around this technology, but it seems to fit with some warped aspects of my personality while offering a lot of potential for immersive storytelling. In a world awash in deepfake videos and Photoshop fiascos, I wouldn’t feel comfortable using the vanishing selfie stick doing journalistic work, but I recorded this video on a day off, so anything goes!

Snow drought update

Despite the seemingly favorable conditions in the video above, the snowpack in many parts of the San Juan Mountains remains below average. The base at Purgatory is still relatively thin, with lots of rocks and plants poking through, plus plenty of unseen obstacles lurking just below the surface. The undersides of my skis have so many scratches they look like they’ve been attacked by a rabid wolverine.

Other parts of Colorado got even more snow from this latest storm cycle, and at least some areas in the West have begun to climb out of a snow drought. This condition can be caused by below-average winter precipitation or “a lack of snow accumulation despite near-normal precipitation, caused by warm temperatures and precipitation falling as rain rather than snow or unusually early snowmelt,” according to the National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS).

"In early January, snow water equivalent (SWE) observations at some SNOTEL stations in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, Oregon, and Washington were at record low values,” according to NIDIS.

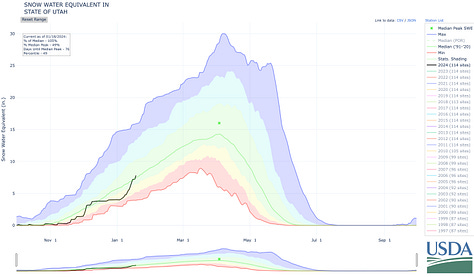

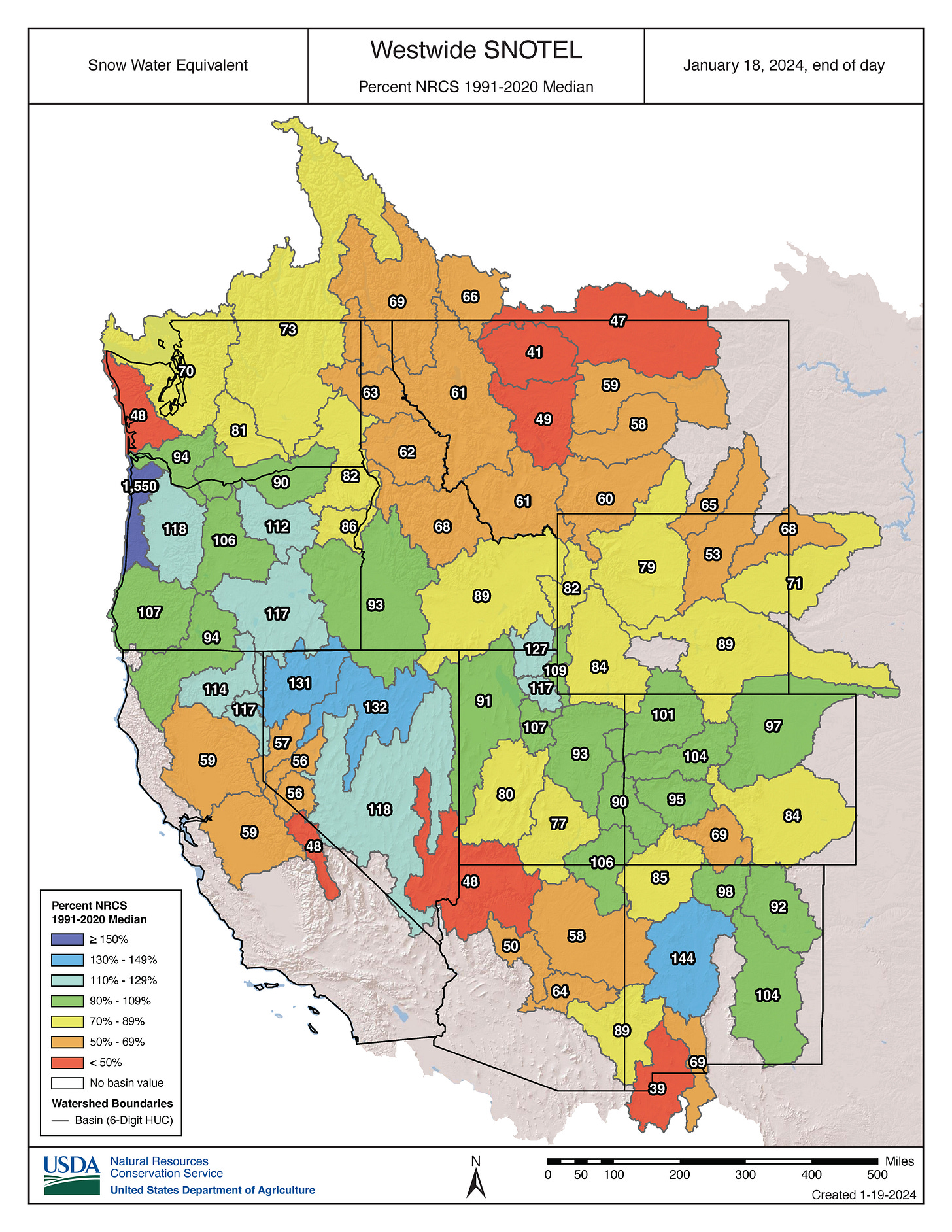

The January 18 graphics below (click to enlarge) show how the recent storminess caused the statewide snowpack in Colorado and Utah to jump. The black line charts this winter’s snowpack and the green line is the 1991-2020 median. I’ve also included Montana, where the snowpack remains at record-low levels (0 percentile!).

The January 18 map below looks better than the one I shared in my prior post, but plenty of places are still hurting for snow.

Climate change and the snowpack

A growing body of scientific literature warns of climate change’s threat to the snowpack. I’m working on a project for The Water Desk that focuses on the story in the American Southwest, but in the meantime, I wanted to share some takeaways from a trio of recent publications that I’ve found helpful if not heartening. All of them explain how climate change has already diminished the snowpack in some places and will cause even bigger problems in the future, especially if we don’t rein in heat-trapping pollution.

New Nature study warns of precipitous decline in snowpack

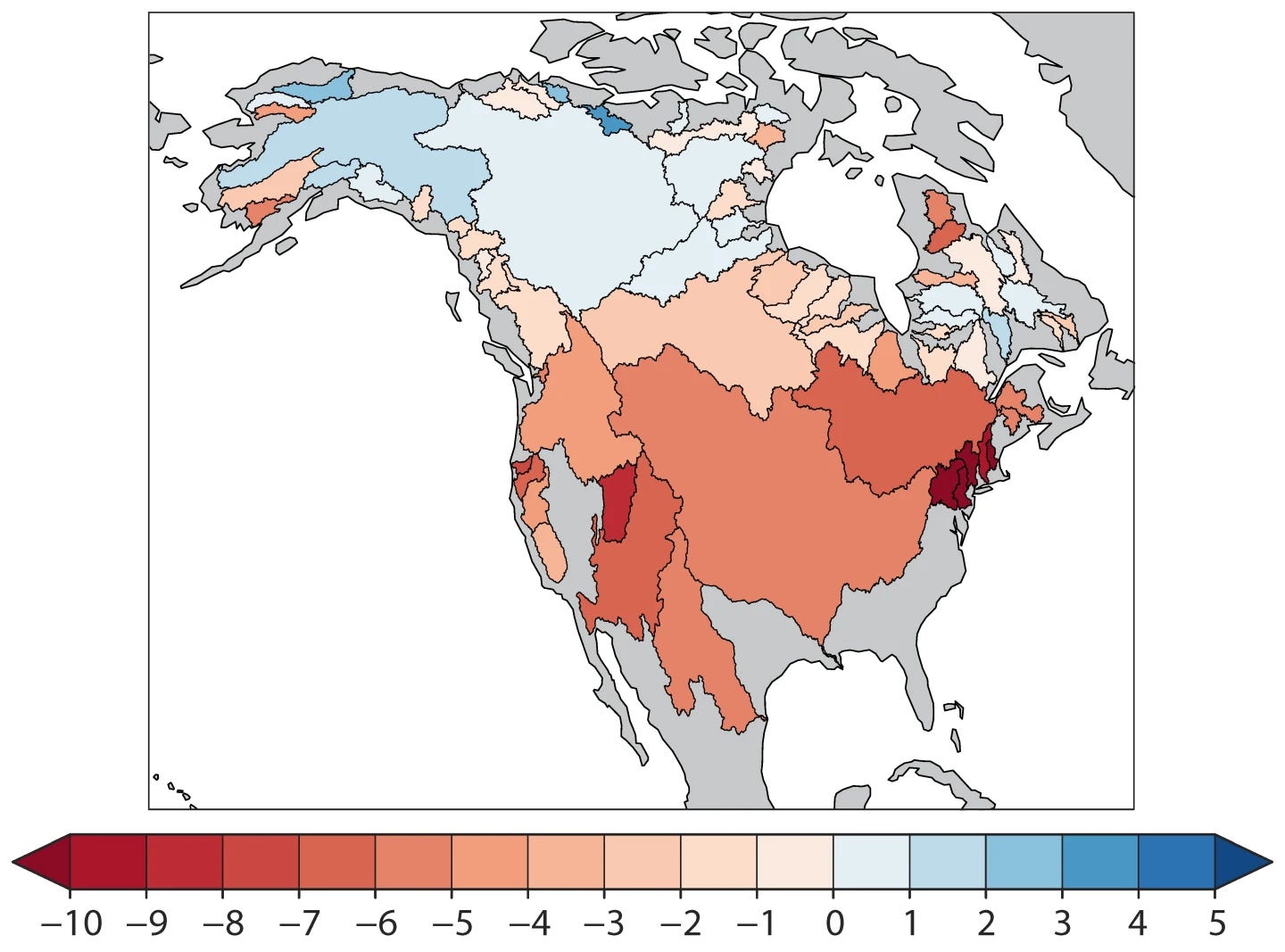

Starting at the hemispheric scale, a new study in Nature from Dartmouth researchers concludes that the snowpack shrunk in the United States and other places around the Northern Hemisphere from 1981 to 2020 (but not everywhere on the planet).

“The sharpest global warming-related reductions in snowpack—between 10% to 20% per decade—are in the Southwestern and Northeastern United States, as well as in Central and Eastern Europe,” according to a Dartmouth press release, which includes this quote from first author Alexander Gottlieb:

The train has left the station for regions such as the Southwestern and Northeastern United States. By the end of the 21st century, we expect these places to be close to snow-free by the end of March. We’re on that path and not particularly well adapted when it comes to water scarcity.

Some frigid basins in Alaska, Canada, and Central Asia actually saw their snowpack grow as climate change increased precipitation and conditions remained cold enough to be favorable for snow. But Gottlieb and co-author Justin Mankin say warming is causing many watersheds to approach a tipping point they call a “snow-loss cliff,” where relatively small temperature rises could accelerate the shrinking of the snowpack in a “highly nonlinear” fashion.

The study concludes that the tipping point for winter temperatures is 17.6°F (−8°C). Seth Borenstein and Brittany Peterson of the Associated Press write about the implications:

Places chillier than 17.6 degrees account for 81 percent of the Northern Hemisphere snowpack, but they don’t hold many people, only 570 million, Mankin said. More than 2 billion people live in areas where winter averages between 17.6 and 32 degrees (-8 and zero Celsius), he said.

What’s key, especially for water supply, is that “as warming accelerates, the snowpack change is going to accelerate much faster than it has,” said Daniel Scott, a scientist at the University of Waterloo who wasn’t involved in the study.

Learn more

“Evidence of human influence on Northern Hemisphere snow loss.” Alexander R. Gottlieb and Justin S. Mankin, Nature 625, 293–300 (2024).

“We’re in danger of falling off a ‘snow loss cliff.’ Here’s what that means.” Maggie Penman, The Washington Post, January 10, 2024.

“Climate change is shrinking snowpack in many places, study shows. And it will get worse.” Seth Borenstein and Brittany Peterson, Associated Press, January 10, 2024.

“Climate change is shriveling critical snowpacks across the Mountain West, study finds.” Kaleb Roedel, KUNR, January 17, 2024.

“Climate Change Behind Sharp Drop in Snowpack Since 1980s.” Morgan Kelly, Dartmouth University, January 10, 2024.

Fifth National Climate Assessment synthesizes research

In November, the federal government released its Fifth National Climate Assessment, a wide-ranging, congressionally mandated report that describes itself as “the US Government’s preeminent report on climate change impacts, risks, and responses.”

One graphic in the report, shown below, depicts how the West’s snowpack changed from 1955 to 2022. “Western snowpack is declining, peak snowpack is occurring earlier, and the snowpack season is shortening in length,” according to the report.

In a map with mostly red circles, I noticed a bunch of (small) blue symbols in places like Colorado’s Continental Divide that buck the regional trend. When I interviewed some of the report’s authors, they pointed to the very high elevations of these sites, which can help preserve their snowpack—up to a point.

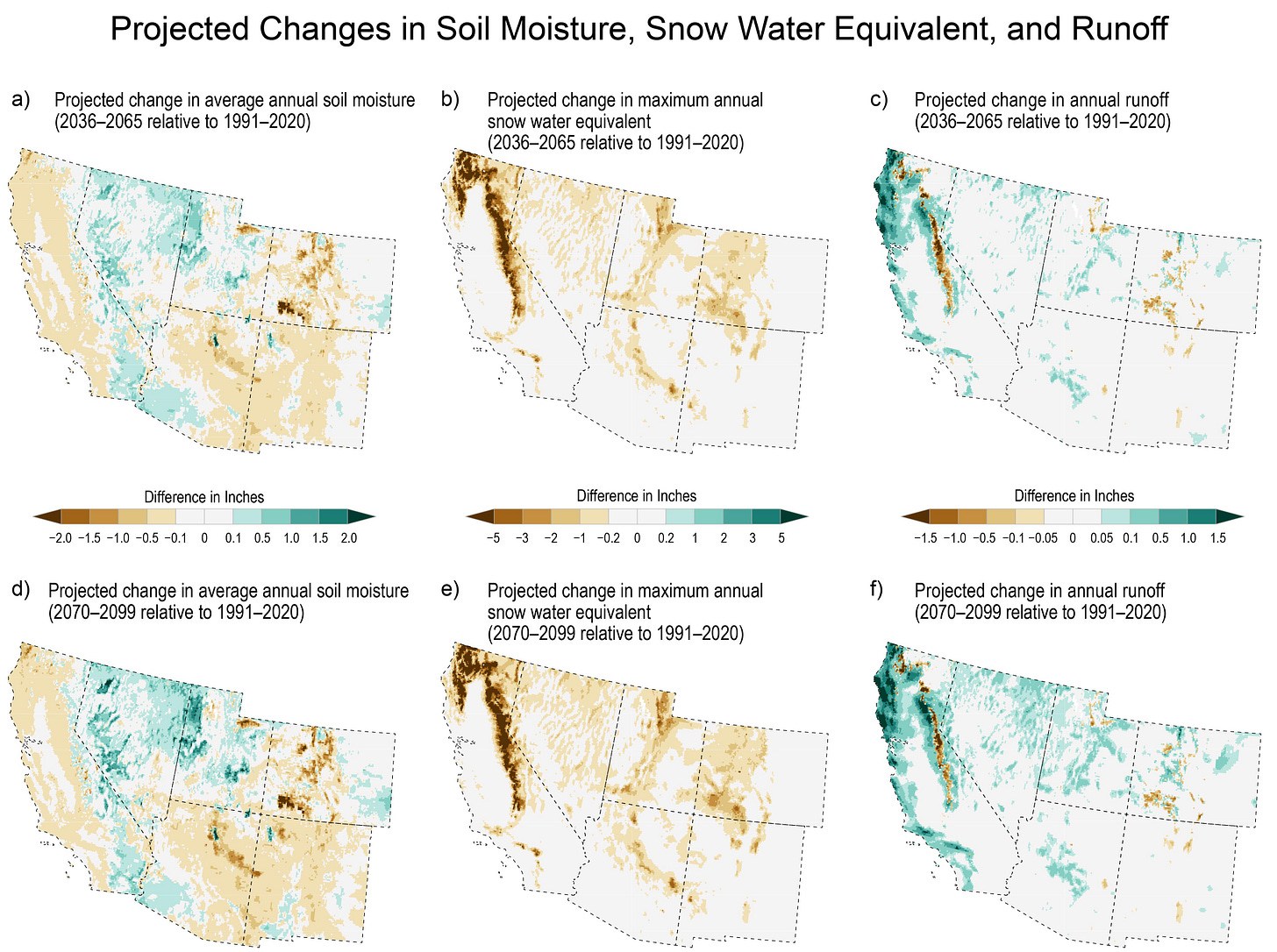

Looking decades into the future, the Fifth National Climate Assessment paints a bleak portrait of the West’s snowpack. In the graphic below, the two middle maps show projected changes in the maximum annual snow water equivalent for two time periods: 2036-2065 on top, and 2070-2099 below, both relative to the baseline of 1991-2020. All that brown is bad news for the snowpack, with the reductions especially dramatic in California.

Learn more

“Fifth National Climate Assessment.” U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2023. (The chapter on water and the regional chapters on the Southwest and Northwest are most relevant for the Western snowpack.)

“National Climate Assessment says snow in the Colorado River basin will decrease 24% by 2050.” Alex Hager, KUNC, November 16, 2023.

Colorado study projects decline in snowpack and streamflows

Colorado’s snowpack is important for tens of millions of people who don’t live in the state, and I don’t just mean skiers coming in for a vacation. Situated along the Continental Divide, Colorado supplies 18 other states and Mexico with water. The state’s snowpack accounts for about two-thirds of the flow in the Colorado River, which supplies more than 40 million people and irrigates millions of acres of farmland.

In a new report from Colorado State University, researchers project that climate change will take a toll on the state’s snowpack and streamflows. “Climate Change in Colorado” looks back at how warming has already affected the state and looks forward to project impacts on water, storms, drought, wildfires, heat waves, air quality, and more. Here’s an excerpt summarizing the report’s findings about the snowpack:

April 1 snow water equivalent (SWE, also known as snowpack) during the 21st century has been 3% to 23% lower than the 1951-2000 average across Colorado’s major river basins.

Future warming will lead to further reductions in Colorado’s spring snowpack. Most climate model projections of April 1 SWE in the state’s major river basins show reductions of -5% to -30% for 2050 compared to 1971-2000; the individual projections that show increasing snowpack assume large increases in fall-winter-spring precipitation.

The seasonal peak of the snowpack is projected to shift earlier by a few days to several weeks by 2050, depending on the amount of warming and the precipitation change. This warming-driven shift could be accelerated by increases in dust-on-snow events.

The table below summarizes expected changes in the state’s hydrology.

Learn more

“Climate Change in Colorado, Third Edition.” Becky Bolinger, Jeff Lukas, Russ Schumacher, and Peter Goble, Colorado State University, 2024.

“Colorado rivers may shrink by 30% as climate change continues, report says.” Jerd Smith and Michael Booth, The Colorado Sun, January 8, 2024.

“Climate report projects continued warming and declining streamflows for Colorado.” Heather Sackett, Aspen Journalism, January 8, 2024.

“Climate change is a threat to Colorado’s snowpack. What does that mean for the water in your tap?” Shannon Mullane, The Colorado Sun, January 9, 2024.

The view from Purgatory

It’s fitting that the place where I ski most often is named Purgatory, which describes itself as “close to heaven” and “fun as hell.” I’ve certainly savored plenty of ethereal days while skiing the many trails with devilish names: Styx, Hades, 666, Demon, El Diablo, etc.

In some ways, I feel like I’m in Limbo (another trail name), having one helluva good time even when the snowpack is subpar and scientists are issuing stark warnings about snow’s future. During the workday, I’ve been reading and writing about infernal climate scenarios; in the evening, I’ve been blowing off steam by editing pretty alpine photos and chuckling while playing with 360-degree videos of face shots.

The Latin word purgare, which means “to purify,” lies at the root of both purgatory and purging. In the religious sense, purgatory was the pit stop where souls go to be purified before reaching a higher plane. Like other locals, I call the ski area “Purg,” but in my mind, it’s also “Purge”—a place where I can cleanse negativity on a run named Nirvana and release pent-up emotions on a trail called Catharsis.

My friend Peter Moore has another theory about why you folks out in the mountains finally started getting some wintry weather recently:

https://petermoore.substack.com/p/every-frozen-dead-guy-has-his-day

Sobering and comprehensive, Mitch. And I dig those 360-degree shots!