Latest snow.news and F is for "flurries"

Plus: photos from Snowmass, one of my favorite ski areas

Here’s a quick rundown of recent snow-related stories that caught my eye . . .

Oregon snowfall projected to drop 50% by 2100 among findings in latest state climate report. Alex Baumhardt, Oregon Capital Chronicle, 1/13/25.

“Oregonians born today are likely to experience a future of more drought, more rain and less snow under warming average global temperatures due to human-caused climate change,” Baumhardt writes about the Seventh Oregon Climate Assessment, which was “authored by more than 65 scientists, experts and engineers.”

Snow scientists say cloud seeding has big potential. Alex Hager, KUNC, 1/20/25.

A new report from the Government Accountability Office examines cloud seeding, which adds chemicals to the atmosphere to induce precipitation. In the studies reviewed by the GAO, estimates for additional precipitation ranged from 0% to 20%, but the report noted it’s difficult to evaluate the technique and its cost-effectiveness because “reliable information is lacking on the conduct of optimal, effective cloud seeding and its benefits and effects.”

Presenting a Complete List of the 509 Active U.S. Ski Areas. Stuart Winchester, The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast, 12/14/24.

On Substack, Winchester shares his master spreadsheet of U.S. ski resorts, which includes ownership, pass affiliations, vertical drop, skiable acres, average annual snowfall, and more. While big conglomerates like Vail Resorts and Alterra Mountain Company have consolidated ownership of some ski areas, I was struck by how many small, independent resorts are still out there.

Protected areas provide habitat for threatened lynx, but wildfire poses risks. U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station press release, 1/6/25.

New research on the Canada lynx found that more than half of the cat’s habitat in the southern Rockies overlaps with protected areas, but that habitat is “sparse, patchy, and poorly connected, existing only in narrow bands due to Colorado’s complex mountainous terrain.” The study, based on data from GPS collars, found that 31% of likely lynx habitat overlaps with forest insect outbreaks and points to future wildfires as another challenge facing the recovery of this threatened species. Snowshoe hares can account for 90 percent of the winter diet of the lynx, which can spot prey in darkness from 250 feet away, according to the release.

Rain on snow: How climate change might be shortening New Hampshire’s winters. Emily Cummings, New Hampshire Bulletin, 12/12/24.

Rain-on-snow (ROS) events can shred the snowpack and cause catastrophic flooding. This story discusses the research of a staff member of the Mount Washington Observatory, where a severe December 2023 ROS event caused an 800-year flood downstream and transformed the snowpack in Tuckerman Ravine from a healthy 83 inches to conditions that were “virtually un-skiable due to exposed rocks and rushing water under the remaining snow.” Data from the observatory, which has been in operation since 1980, revealed a 17% increase in ROS days from 1981-2010 to 1991-2020, with a 46% increase in the month of December.

'Snow Way, José!' Here's what New Mexicans named our snowplows. Gillian Barkhurst, The Albuquerque Journal, 1/16/25.

New Mexico runs an annual contest to name its snowplows and received nearly 700 entries this year. Other winning names include Snow Bueno, Chips & Que Snow, En-CHILL-ada, and Red Chilly Brrrr-ito.

SnowSlang: F is for “flurries”

Sadly, we’re in a snow drought here in southwest Colorado, so the meager volume of flakes has tended toward dustings rather than major-league dumps. That got me thinking about the definition of flurries, plus some other categories of snowfall.

A “snow flurry,” according to the American Meteorological Society’s Glossary of Meteorology, is a “common term for a light snow shower, lasting for only a short period of time.” A “snow shower,” in turn, is “a brief period of snowfall in which intensity can be variable and may change rapidly.”

I posed the following query to ChatGPT: “complete this analogy: flurry is to snow as X is to rain” (all that studying for the SAT in the late 1980s still hasn’t worn off!)

At first, the chatbot returned “drizzle,” but that doesn’t sound right to me because such precipitation is defined by small droplet size—and enough drizzle adds up to measurable rain. ChatGPT’s runner-ups included “sprinkle,” which I kinda like. Two other chatbots—Gemini and Claude—preferred “shower,” which doesn’t seem specific enough.

The etymology and evolution of “flurry” is interesting. Merriam-Webster says its first known use was in 1686, and the word probably came from “flurr,” which means “to throw scatteringly.” The Oxford English Dictionary dates the first usage to 1698, when the word signified “a sudden agitation of the air, a gust or squall.” The origin of “flurry” may be onomatopoeic, meaning its sound resembles its meaning. In the 19th century, the term started to be used to describe precipitation and “a sudden rush (of birds),” according to the OED.

We now use “flurry” to describe “a brief period of commotion or excitement” or “a sudden occurrence of many things at once,” according to Merriam-Webster. Many news outlets have used the term to describe Donald Trump’s blizzard of executive actions. In the financial context, the word also means a burst of buying or selling with a rapid change in prices.

Flurries are just one type of snowfall. I found this set of definitions of winter precipitation types at NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory:

Snow Flurries. Light snow falling for short durations. No accumulation or light dusting is all that is expected.

Snow Showers. Snow falling at varying intensities for brief periods of time. Some accumulation is possible.

Snow Squalls. Brief, intense snow showers accompanied by strong, gusty winds. Accumulation may be significant. Snow squalls are best known in the Great Lakes Region.

Blowing Snow. Wind-driven snow that reduces visibility and causes significant drifting. Blowing snow may be snow that is falling and/or loose snow on the ground picked up by the wind.

Blizzards. Winds over 35mph with snow and blowing snow, reducing visibility to 1/4 mile or less for at least 3 hours.

I can tell you from personal experience that snow squalls also happen in Colorado. The most terrifying drive in my life featured me passing through a squall while I was crossing Vail Pass on I-70 in the dark on December 22, 2020.

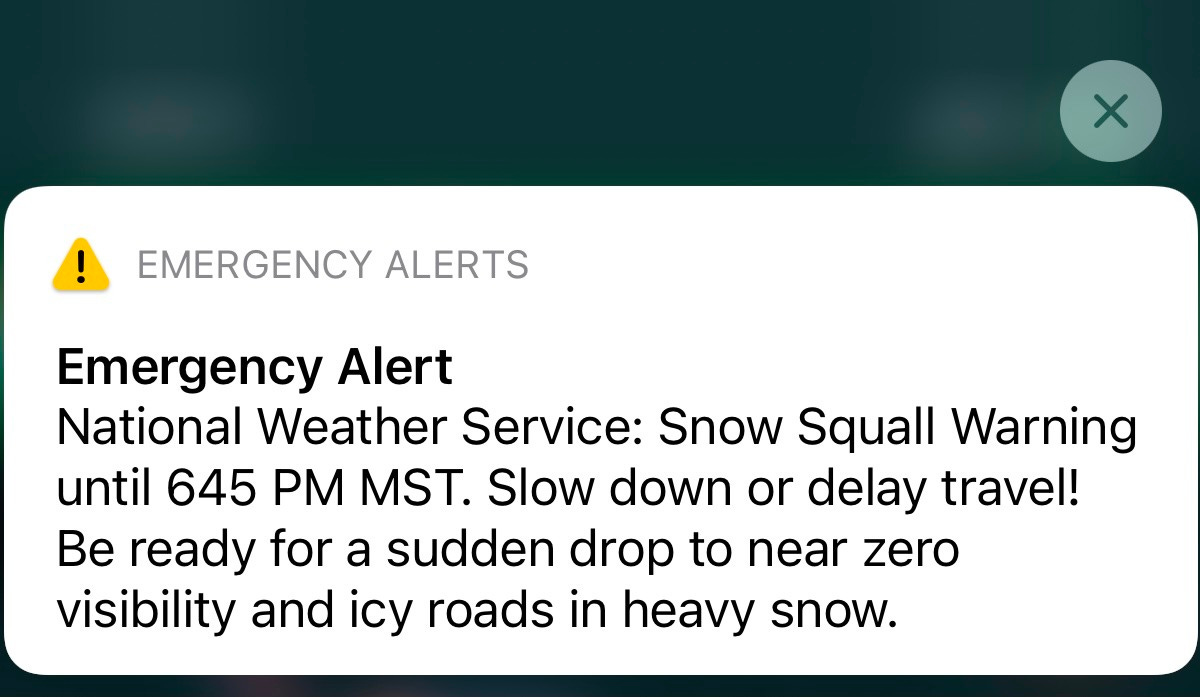

I’ve never seen it snow that hard: squall is flurry's antonym. I even received a National Weather Service emergency alert on my phone:

I could barely see the end of the hood on my 4Runner. It didn’t matter that I was in four-wheel drive and had newish snow tires: my traction was lousy, so I was skidding all over the highway.

The handful of other fools on the road also had their hazard blinkers on. Some vehicles just stopped in the middle of the interstate, which seemed like an invitation to being rear-ended, yet the narrow shoulder was buried in snow that could either entrap me or send me spinning off the road, so I white-knuckled it and proceeded down the pass at a glacial pace.

Conveniently, a state trooper came along with his roof lights illuminated, allowing a few of us to follow behind his shining beacon. After about 10 minutes, the squall had moved on, but my heart rate stayed elevated long after.

Moral of the story: don’t mess with snow squalls, and savor the beauty of snow flurries.

Snowmass photos and John Denver videos

I had the good fortune to visit Snowmass last week to ski with some buddies. Snowmass is one of my very favorite mountains, in part because it was the first place I ever skied in Colorado, way back in the early 1980s, when I was in middle school and took a trip there with my best friend.

It’s one of the largest ski areas in Colorado but relatively far from the Front Range, so it tends to be less crowded, and the scenery is spectacular, especially those epic views of the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness.

The resort tops out at an impressive 12,510 feet, so there’s a lot of expansive tundra above treeline. At lower elevations, you can thread through some gorgeous glades with widely spaced trees. Below are some photos from the trip.

If you’re still with me, I’d be remiss in invoking John Denver without also sharing this video below of him skiing and singing “Dancing with the Mountains.” It’s got ski ballet, early snowboarding, and the singer showing off some fancy moves on skinny skis while wearing a sweet onesie and sick sunglasses.

And if I share that video, I’d also be remiss in not offering up this 2017 re-creation that was filmed at Alta: