Greenland aerials and the latest snow.news

A glimpse of the Arctic, this season's early meltout, a dust-on-snow study, and more.

I’m back from a wonderful, snow-free vacation in Greece and Italy, but I must admit that one of the trip’s highlights was flying over the snowy southern tip of Greenland on the London-to-Dallas leg of our epic 25-hour journey home.

Sadly, clouds obscured the view of Greenland for nearly the entire time we were above the massive island. But for about 10 minutes, the skies cleared somewhat, allowing me to catch occasional views of the rugged, snow-clad terrain below, as well as the coastline dotted with bergs and floes.

What a wild part of the planet!

At the time, virtually every window shade in the Boeing 777 was shut, but there I was, allowing brilliant light to flood into the cabin, and drawing a few glares from my fellow passengers. In response, I took one of those thin blankets they give you on long-haul flights and draped it over my head and the window to minimize the intrusion.

Readers of snow.news know that I love aerial photography. I’ve sometimes been fortunate enough to fly in single-engine prop planes with the window open and use a nice camera to capture the scene below. On this trip, however, I only had my iPhone, and the shooting conditions were lousy: scratches, dirt, and ice crystals on the tinted window made it so hard to get a completely clear view.

Even so, the quick glimpse of Greenland filled me with wonder and a desire to somehow see the place in person. Greenland, which has been in the news lately due to the Trump administration’s interest in adding it to the United States, is home to the second-largest expanse of ice on the planet (behind Antarctica). The fate of all that frozen water bears heavily on such issues as sea-level rise, Earth’s albedo, and the circulation of ocean currents that help govern the weather.

Greenland is also one of the world’s biggest producers of icebergs. After passing over the island, I killed more than three hours of the flight by watching The Titanic for the first time. I enjoyed the movie but found the depiction of hypothermia more engaging than the romance—go figure.

On the final leg of our journey home—a late-night flight from Dallas to Durango—I was treated to another astonishing aerial view. Around midnight, an impressive line of intense thunderstorms near Abilene and Lubbock forced our short-haul regional jet to make a long detour to the southwest.

For about 20 minutes, we paralleled a bank of cumulonimbus clouds that produced a stunning display of lightning, with pulses of light visible every few seconds from my vantage point. The bolts illuminated the puffy clouds from within, defining their features in high relief. I could imagine icy hailstones pelting the ground below.

In a world with so much depressing news, it’s nice to enjoy a little awe now and then. The fact that these ineffable episodes are so tough to capture in images or words is exactly the point.

Colorado River runoff goes from bad to worse

Speaking of downers, the runoff picture in the Colorado River Basin and other parts of the West has taken a turn for the worse.

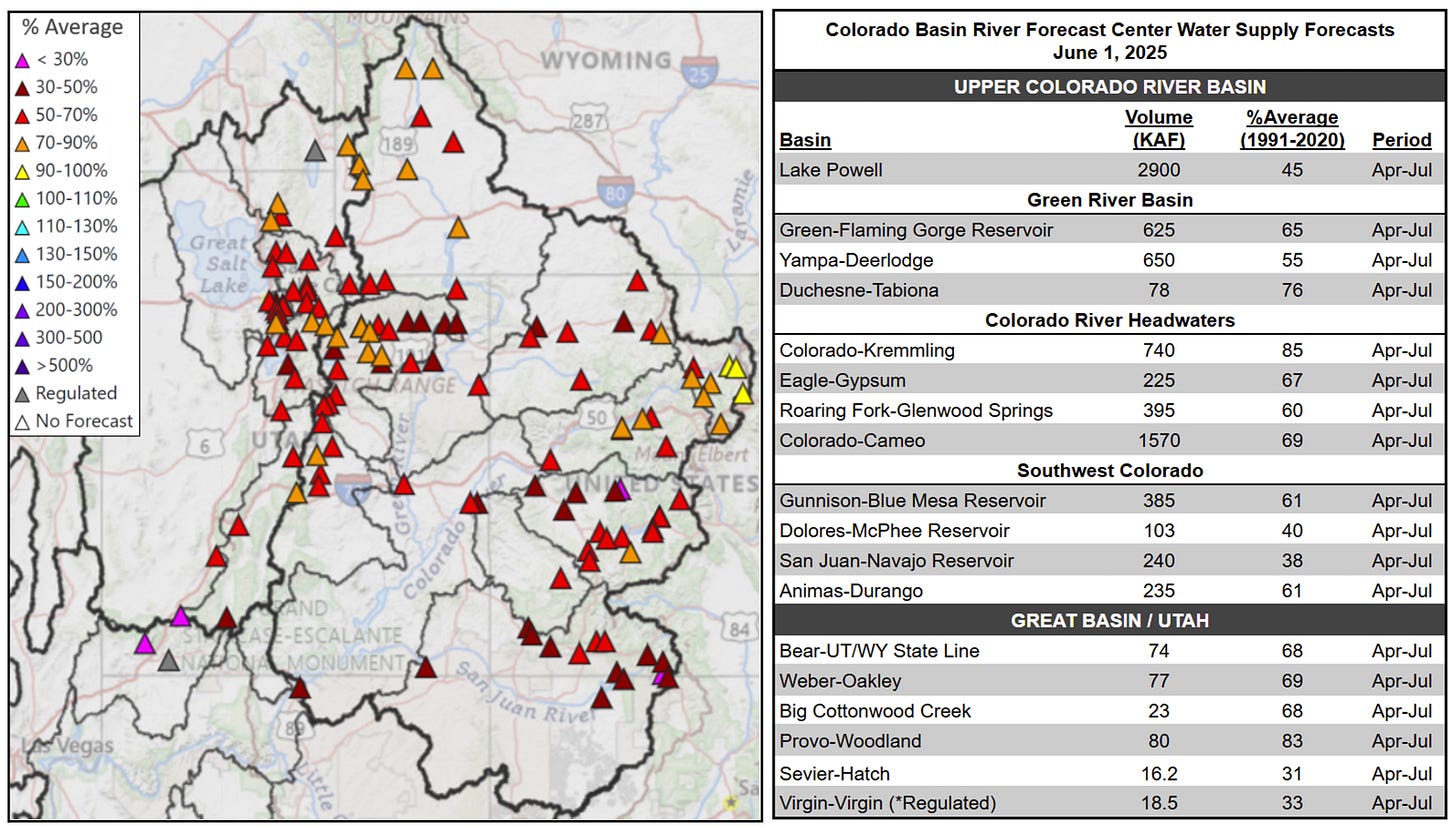

The June 1 runoff forecast from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center showed that inflows to Lake Powell have declined to 45% of the 1991-2020 average, down from 55% on May 1 and 67% on April 1.

If you’re scoring at home, the graphic below has the numbers, with all those red, orange, even magenta triangles dictating meager flows of snowmelt. Near its headwaters, the Colorado River above Kremmling was at a respectable 85% after a decent season in parts of northern Colorado, but other major tributaries were all lower—sometimes much lower—such as the San Juan at Navajo Reservoir (38%), the Dolores at McPhee Reservoir (40%), the Yampa at Deerlodge (55%), and the Roaring Fork at Glenwood Springs (60%).

The pronounced shift in the snowpack and runoff prompted the National Integrated Drought Information System to put out a special update on May 20.

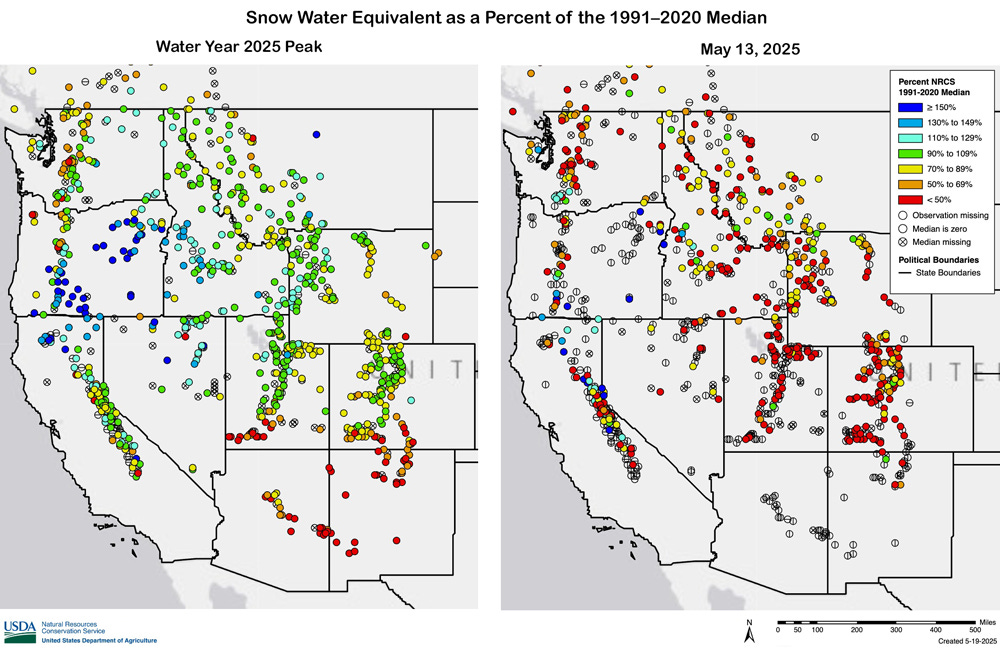

“Nearly all western basins are now in late season snow drought, despite many stations reaching near to above-average peak snow water equivalent (SWE) during the snow accumulation season,” according to the update. “Some stations, including some in Nevada, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico, saw record early melt out.”

In the graphic below, the map on the left depicts SWE levels at their peak, while the right map shows the steep declines that took place by May 13—all of those red dots indicate readings of less than 50% of the long-term median.

The grim stats for runoff in the Colorado River Basin have injected increasing urgency into the ongoing negotiations over the river’s fate and how seven U.S. states will share the pain of reduced flows in an era when climate change is straining the supplies of the oversubscribed river. For more on that, see stories here and here.

Dust’s influence on the snowpack (and much more)

When dust lands on the snowpack, it accelerates melting by absorbing more solar radiation. A recent study, published in March in Geophysical Research Letters, quantifies the impact of dust on snow for the Colorado River, which supplies some 40 million people in the U.S. and Mexico.

Based on 23 years of daily, remotely sensed images, the study found the dust’s impact on the melt season in the Upper Colorado River Basin was “greatest in the central-southern Rocky Mountains at mid-alpine elevations.”

“Over time, snow darkening and accelerated melt were generally higher in the first half of the record with a slight declining trend across the full record. However, dust contributed to accelerating melt every spring over the record,” according to the study’s plain language summary.

Led by University of Utah scientists, “the research is the first to capture how dust (affects) the broad expanse of headwaters feeding the Colorado River system,” according to a press release from the school, which also includes this quote from Patrick Naple, lead author of the study:

“It’s not just how much dust gets deposited over a season, but also the timing of dust deposition that matters . . . Dust is very effective at speeding up melt because it’s most frequently deposited in the spring, when days are getting longer and the sun more intense. Even an extra millimeter per hour can make the snowpack disappear several weeks earlier than without dust deposition.”

For more on the study, see this Q&A between KJZZ’s Mark Brodie and the University of Utah’s McKenzie Skiles, another author of the paper.

And if you want to learn more about the many effects of dust on the environment, human health, and the economy in California, several schools in the UC system recently released a report, “Beyond the Haze,” that chronicles the problems, including impacts to the Sierra Nevada snowpack that is so vital to the state’s water supply.

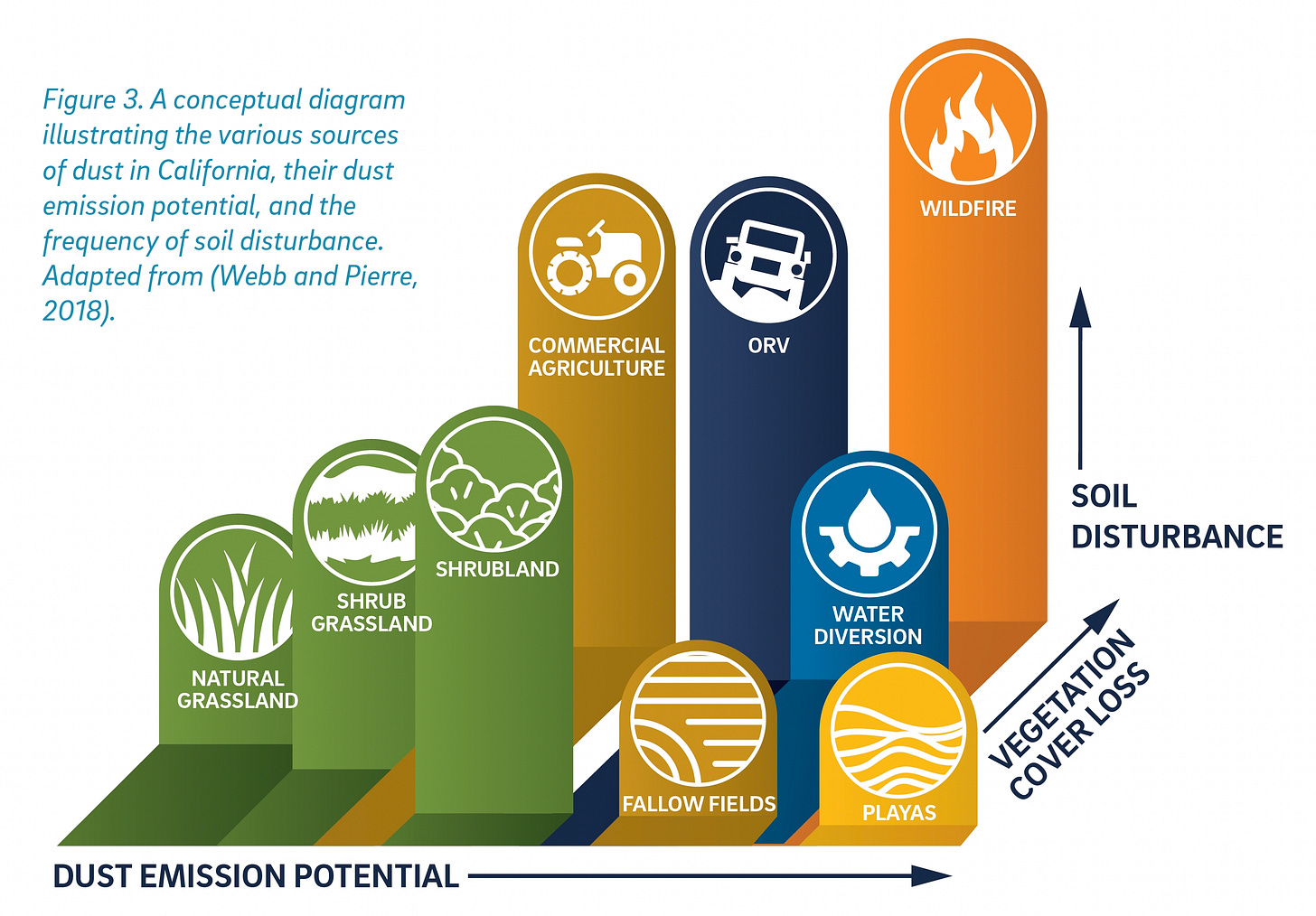

Where is California’s dust coming from? The UC Dust initiative’s report features this elegant explanatory graphic on the various sources, their dust potential, and the underlying causes.

I’d love to see a version of this graphic for the Colorado Plateau and other locations, but the underlying situation remains the same across the West: native habitat, other than places like the dried lakebeds of playas, isn’t necesarily and naturally dusty—it’s the human-caused disturbances that are the real culprit in mobilizing the particles. “In addition, climate-change enhanced drought and wildfires have likely increased dust emissions over levels before the arrival of settlers in the 19th century,” according to the California report.

Odds and ends

Below are some more snow-related stories that recently caught my eye . . .

🌨️ Snowflakes, death threats and dollar signs: Cloud seeding is at a crossroads, Alex Hager, KUNC, April 21, 2025.

🌡️ Why climate researchers are taking the temperature of mountain snow, James Temple, MIT Technology Review, May 14, 2025.

💦 Looking to the Pacific, scientists improve forecasts of atmospheric rivers, David Hosansky, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, April 17, 2025.

⚠️ Avalanche Detecting Drones Could be Coming to a Ski Resort Near You, Ian Greenwood, Powder, May 21, 2025.

👽 Did it rain or snow on ancient Mars? New study suggests it did, Daniel Strain, University of Colorado Boulder via EurekAlert!, April 21, 2025.

⛷️ Prehistoric skis: Melting glaciers reveal clues to climate adaptation in Norway's mountains, Emily Cohen, Earth Institute at Columbia University, April 7, 2025.

💰 The truth about the ‘chalet girls’ who look after the needs of Europe’s wealthy skiers, Jack Hillcox, CNN, April 23, 2025.