Fall storm report and two new features

Say hello to SnowSlang and SnowVis

A potent fall storm made it feel downright wintry in Colorado’s high country over the weekend.

Initial forecasts called for more than two feet of snow at Purgatory, my home mountain, raising hopes the resort would open a month earlier than scheduled.

Alas, the storm was a warm one, spinning over the Arizona desert for a couple of days, where Phoenix had recently logged an incredible 21-day streak of record autumn heat.

The system, which caused deadly and catastrophic flooding in Roswell, N.M., pumped a ton of moisture into the San Juans. Nearly 3” of rain fell at the snow.news headquarters—a real drenching for these parts—but only the highest elevations around here were blanketed in snow. We got nary a flake, but at least I could see some of the white stuff on surrounding ridges.

To the east, Wolf Creek just started up Tuesday, becoming the first ski area in North America to open this season, but my dreams of skiing in mid-October at Purgatory were dashed by the relatively high snowline. That crucial dividing line between rain and snow, which not only matters for skiers but also water managers, forest ecosystems, and innumerable species, is bound to climb on a warming planet.

When I looked at Purg’s webcams Sunday morning, here’s what I saw at the top of Lift 1 (10,485’) and at the base (8,793’).

I know there’s a big difference between weather and climate, but I couldn’t help but wonder if this would’ve been a sick early-season powder day had the calendar read 1984 or 1974. Then again, maybe it was climate change that spun up the storm in the first place!

After the skies cleared, I drove up beyond Purgatory to Coal Bank Pass and took a beautiful hike/trudge through the snow on Pass Trail so I could admire the fresh coat on Engineer Mountain and the surroundings.

Under bluebird skies and the relatively high October sun, it didn’t take long for me to start broiling and shedding layers as I watched the snow beneath my feet start to melt and metamorphose.

The trail had already been broken by at least one skier, one hiker, one dog, and one horse (probably two based on the abundance of manure), yet it was still way harder than hiking on solid ground. I was sweating bullets in the sun, chilled in the dense conifer forests, and reminded of why snow scientists pay so much attention to what the sun is doing and the wild fluxes of energy that result.

Back at the trailhead, I took a gander at the Spud Mountain SNOTEL station, plus another collection of monitoring equipment that had a label for the Colorado Avalanche Information Center. The SNOTEL station recorded a snow depth of 15" on Monday, but it has since fallen to 8". Thankfully, there’s more snow in the forecast for next week.

New features at snow.news

Now that there’s at least some snow on the ground and the new 2024-2025 water year is underway, it’s time for me to act upon a resolution: publishing more consistently and pursuing some new features for snow.news, which I introduce below.

My goal this season is to be more modular by breaking up the content into smaller chunks, including some recurring features that I’ll periodically sprinkle throughout the editorial calendar . . .

SnowSlang: the language of snow

The writer in me is fixated on words related to snow, skiing, and snowboarding, so in 2016, I started SnowSlang.com, an offbeat blog that offers explanations of the terminology. To date, the most widely read work in my career is a half-baked look at the etymology of shred the gnar.

SnowSlang has focused on snow sports, but I’m shifting gears to concentrate on snow itself and snow science. As I’ve been educating myself about snow and the wider cryosphere, I’ve encountered plenty of unfamiliar terms—and realized that my understanding of some things was primitive or outright wrong.

I’ve been a generalist most of my career, sometimes even working as a “general assignment reporter,” so after many crash courses, I know that one of the most helpful steps for becoming conversant in a subject is to learn the lingo (and acronyms).

As part of my work for The Water Desk, I’m building an illustrated glossary of snow-related terms, so I’ll be sharing some of the content here, in alphabetical order, of course.

So let’s kick things off with . . .

A is for Albedo

Albedo is a measure of the fraction of solar energy that is reflected from a surface. It ranges from 0 to 1. Surfaces with very high albedo, such as snow and ice, reflect a large fraction of incoming sunlight, while those with low albedo, such as bare ground or open water, absorb most of the energy. Albedo is derived from the Latin word for white, albus.

The Earth’s overall albedo is 0.3, but fresh snow can be around 0.9, which is why you can get a nasty sunburn on the slopes in winter. The albedo values of various other materials are in the graphic below that I created using data from MOSAiC: Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate.

(If you’d like to see a slightly different take, using data from Penn State, I made an alternate version of the chart here.)

Dust-on-snow events can dramatically decrease the albedo of the snowpack and hasten its melting. So can the deposition of charred material from forests scorched by wildfires.

On a global scale, albedo plays an important role in climate regulation. The less ice there is on the planet, the more solar radiation is absorbed, leading to further warming. Conversely, an increasingly frosty planet reflects more and more sunlight, cooling the planet further, freezing more ice, and so on, which is what happened to the planet when it turned into “Snowball Earth” many hundreds of millions of years ago.

In the next installment of SnowSlang, I’ll be moving on to “B,” and yes, I do have options for tougher letters like K, Q, X, and Z!

SnowVis: data visualizations related to snow

Longtime readers of snow.news know that I have a soft spot for hard data and cool visualizations of interesting information. I’m a visual learner who craves charts, maps, infographics, and other tools that efficiently communicate vast quantities of information. In learning about snow, I’ve found some visuals to be super helpful, so I’d like to start sharing them on a regular basis.

Some of these visuals are pretty basic and more about the message than the medium, but I’m also going to include more intricate figures from scientific papers. Most visualizations in peer-reviewed articles are intimidating and beyond simple explanation (or my understanding), so I’ll be steering clear of those, but I have found plenty of visuals that are both accessible and enlightening.

I’ll also share some graphics and maps I’ve created myself, though my data vis skills are modest. Python and R scare me, but I used to be pretty good at Excel and Tableau, and now I’ve found Datawrapper to be my tool of choice. As with polling, I’m more of a consumer than a producer of the material.

So that’s SnowVis. Without further ado, let’s get to . . .

U.S. snowfall maps

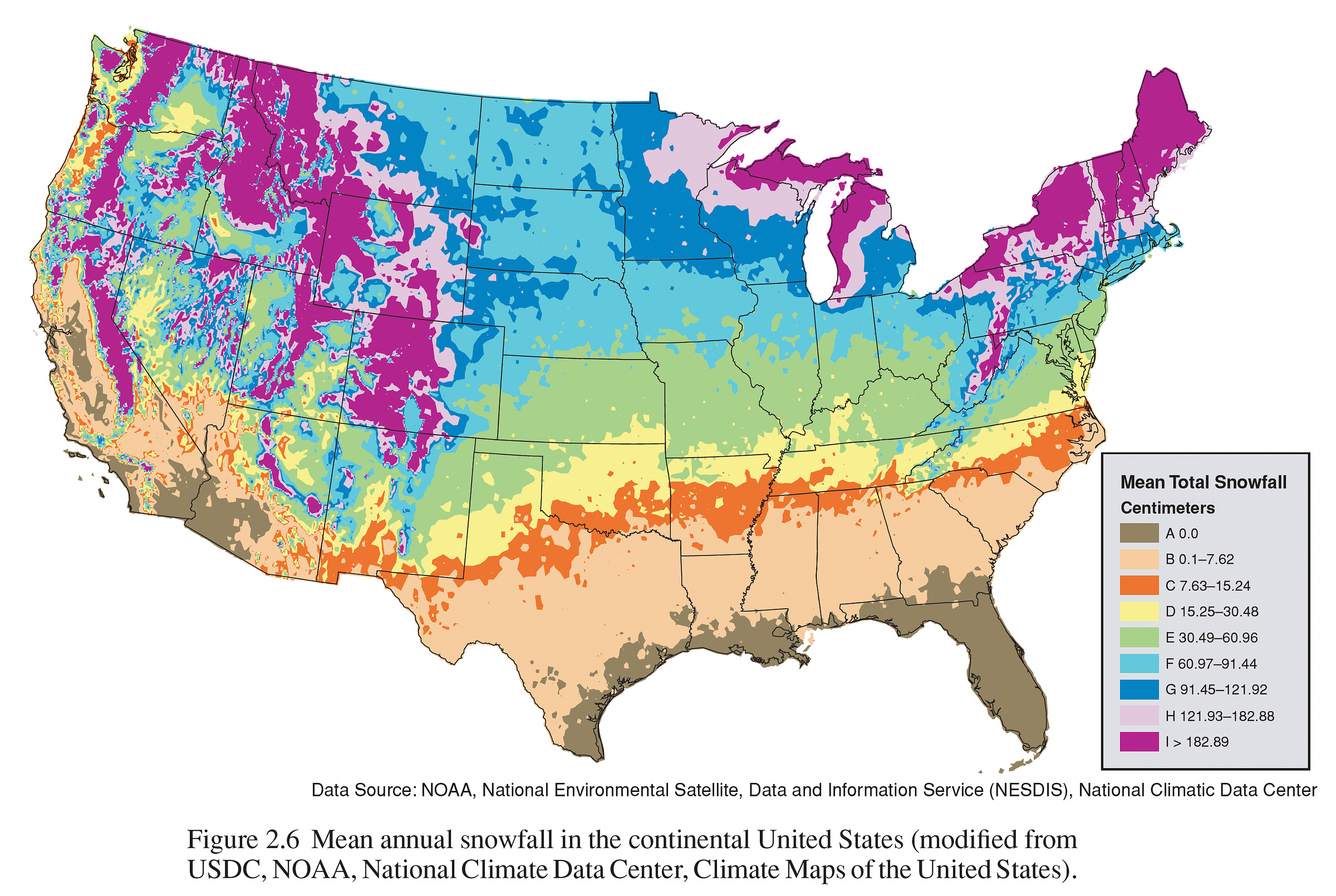

With some parts of the nation receiving their first snowfall, I was curious about what the pattern of snowfall looks like in America. I found the map below in Principles of Snow Hydrology, a book I recently started.

The colors and legend are in centimeters; for reference, the peach-colored “B” category is up to 3", and the purple “I” places get more than 6 feet of snow on average. Putting aside Florida, where the mean snowfall is 0 virtually everywhere, all of the states in the contiguous United States have sizable areas where the figure is non-zero.

The map below, which I downloaded from Pivotal Weather, shows the total snowfall for the 2023-2024 water year. In this case, the maximum snowfall of 10+ feet is shown in the lightest beige regions, which match pretty well with the purples in the map above.

When is the first snow expected across the country? In the map below from NOAA, the dots are colored according to “the date by which there’s a 50% chance at least 0.1" of snow will have accumulated, based on each location’s snowfall history from 1981-2010.”

I’d be curious to see how this map morphs due to climate change. As NOAA’s accompanying post notes:

For any given place, the date of the first snow of the season may be affected by our changing climate. But not necessarily in obvious ways. For starters, we know that in the long-term, Northern Hemisphere snow cover isn’t changing dramatically for most of the autumn months. (Spring is another story.) And even in a warming world, there is still plenty of sub-freezing air hanging around in October in parts of the Canada and the Arctic. Meteorological systems can still yank this cold air into place to support snowfall just like they did 50 years ago, and can still do it fairly early on the calendar.

You may notice that in the middle of the country, there’s a northeast tilt to the coloring of the dots rather than a straight east-west pattern, with earlier dates dipping farther south in the western plains compared to the Midwest. “This has a little bit to do with elevation,” NOAA says, “but more to do with the fact that the coldest air associated with many winter storms—including early winter storms—often barrel down the high plains, corralled by the Rockies to the west.”