SnowSlang: D is for "deicing"

Plus: aerial photos from a successful Durango-Denver flight and maps showing the odds of a white Christmas

If you fly during wintry weather, your plane may need to make a pitstop before takeoff so it can go through a critical step that prevents the aircraft from crashing.

Deicing is the process by which ice and snow are removed from an aircraft's surface so that the frozen contaminants don’t mess with the plane’s aerodynamics.

On a flight last week out of Durango, we went through the procedure and made it safely to Denver without slamming into terra firma. I was also relieved that the residue of the deicing fluid only obscured the view from my window during the first few minutes of the flight (I’m a little obsessed with aerial photography and find the window seat the only redeeming quality of air travel).

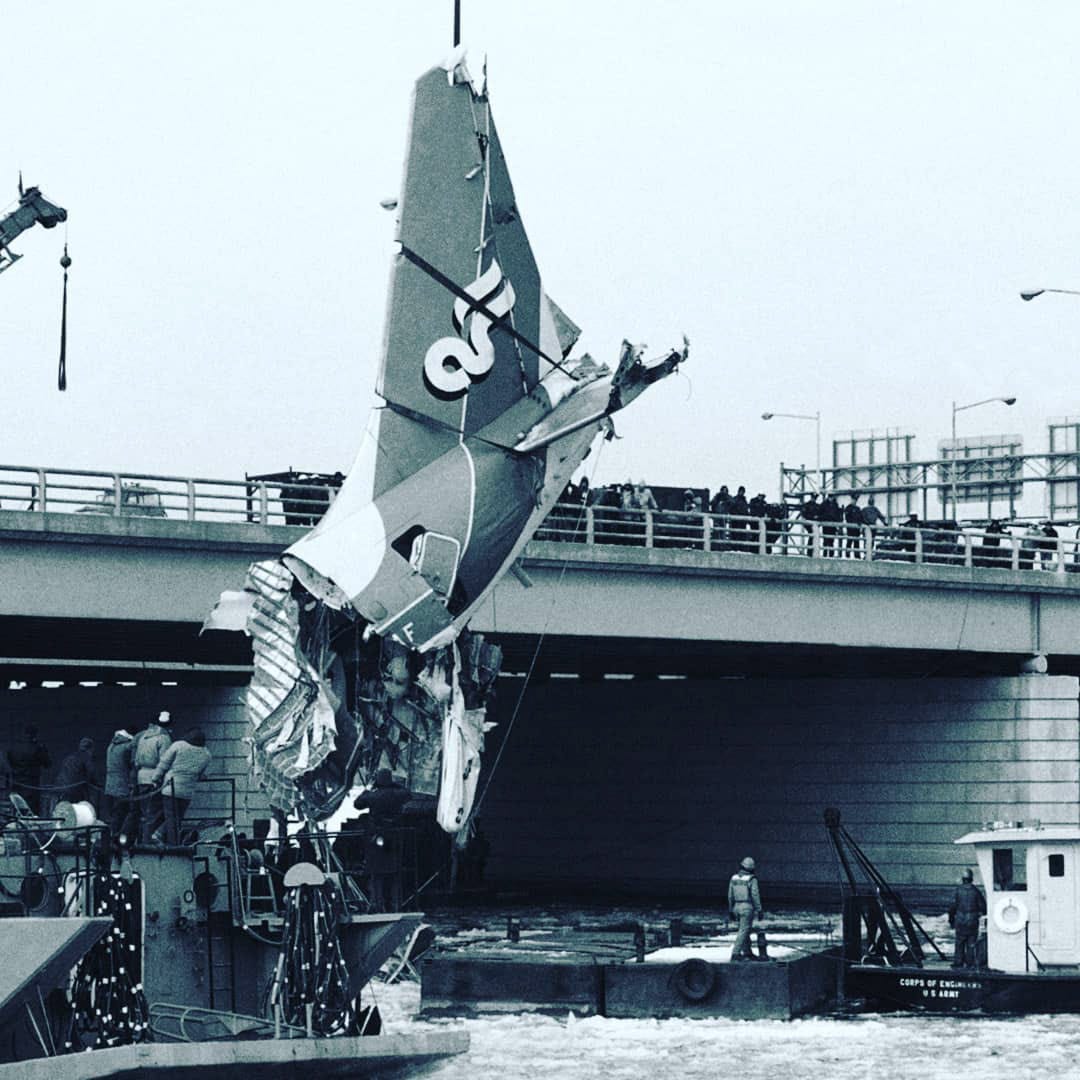

One of the most infamous airline tragedies associated with ice and winter weather was the January 13, 1982, crash of Air Florida Flight 90 into the Potomac River during a heavy snowstorm as the plane departed Washington National Airport (now called Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport). All but four of the 74 passengers died, as did four of five crew members and four motorists on the 14th Street Bridge.

“Loss of control was determined to be due to reduction in aerodynamic lift resulting from ice and snow that had accumulated on the airplane's wings during prolonged ground operation at National Airport,” according to the Federal Aviation Administration. “Even small amounts of frost, ice, or snow can have catastrophic effects on airplane performance.”

Deicing was used prior to Flight 90’s takeoff, but the nozzle delivered a solution that was too weak, and too much time elapsed before the plane took off, allowing frozen material to accumulate on the wings.

The crew, which had limited experience flying in winter weather, turned off an engine anti-icing measure, and a sensor was apparently plugged with ice, leading to erroneous data on the engine’s thrust. It was so snowy at the airport that the plane had trouble pushing back from the gate and needed a tug equipped with tire chains to help it maneuver.

The tragedy in the nation’s capital changed winter aviation practices at home and abroad, as the FAA notes:

The crash of Air Florida Flight 90 was a major catalyst for significant advances in the safety of winter weather operations, particularly in the area of airplane deicing technology and procedures. Numerous initiatives were undertaken in order to better understand the properties of deicing materials, techniques for their application, and related training programs.

The D.C. crash was hardly the first nor the last case of ice and snow causing planes to fall from the sky. Wikipedia lists no fewer than 46 cases of frozen water causing airliner accidents around the world.

I’ll spare you a treatise on the various types of treatments, but there’s a distinction between deicing fluids, which remove the frozen contaminants, and anti-icing solutions, which prevent subsequent freeze-up before takeoff.

Heated propylene glycol, which lowers the freezing point of water, is the most common chemical used, but it’s also mixed with other ingredients, such as thickening agents, corrosion inhibitors, and dyes that allow crews to see what surfaces have been treated.

For more on how planes are deiced, check out this video from the Wall Street Journal:

Below is another take from Southwest Airlines, told through the voices of the good folks who apply the fluids, sometimes while sitting in an open-air bucket and exposed to the elements.

Window seat photos: Durango 🛩️ Denver

I believe that anyone who flies in an airplane and doesn’t spend most of his time looking out the window wastes his money. – Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert

On daytime flights, you’ll typically find me in one of the very last rows, sitting near the toilet, because that’s usually the only place I can book a window seat without paying those upcharges for so-called premium seats.

This is especially true on the ~45-minute short-haul hop between Durango and Denver, which is gorgeous and fascinating from takeoff to landing, assuming that Colorado isn’t blanketed by clouds.

Below are some snowy photos from the flight, with locations in the captions. In all of them, I’m looking toward the northwest.

SnowVis: predicting a White Christmas

I’m Jewish, so I can’t say that I’ve been dreaming of a white Christmas, but that possibility is certainly a big deal here in the United States.

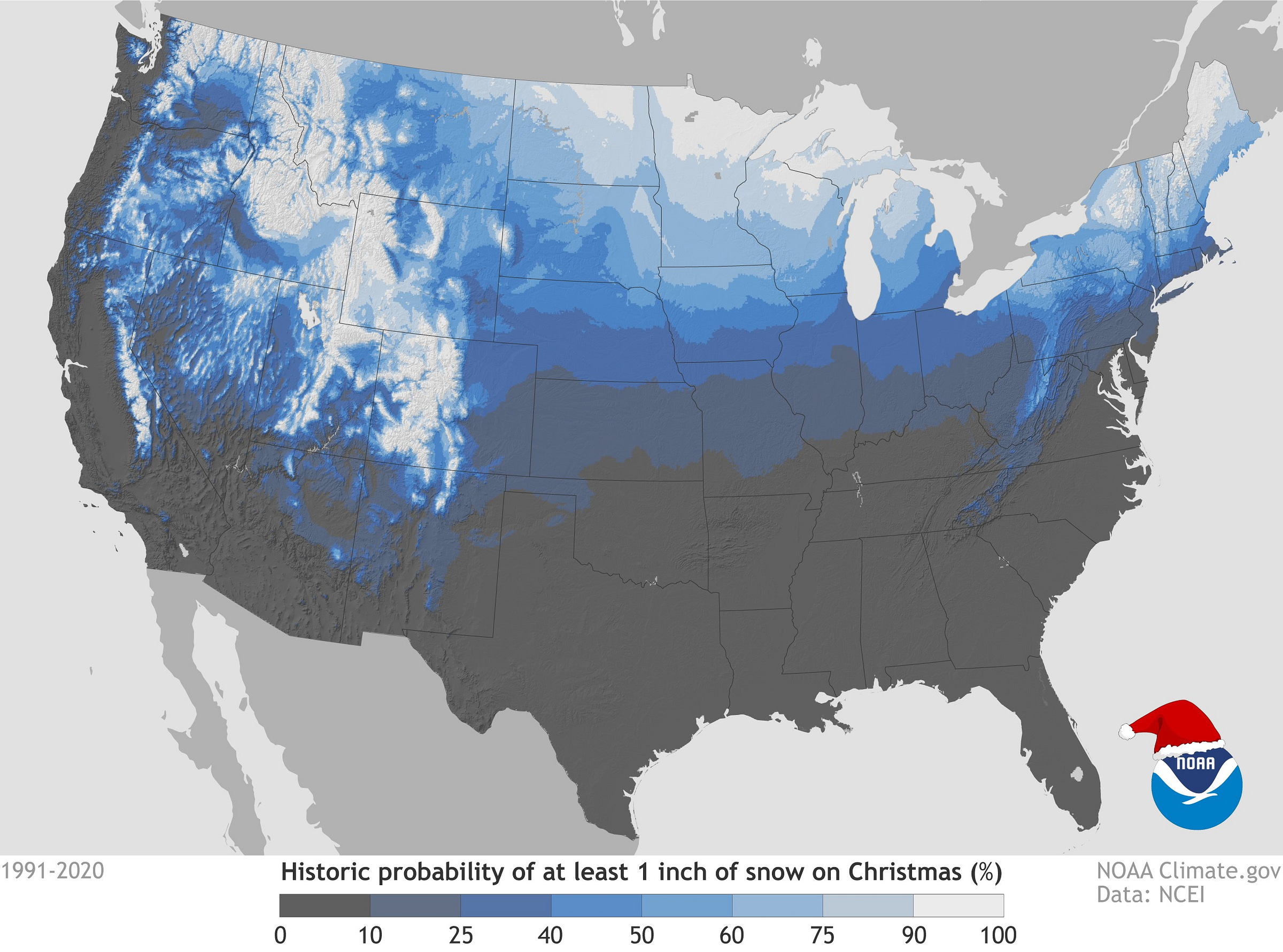

Accordingly, even the federal government has analyzed the probabilities, as shown in the map below. The graphic illustrates the chances of there being at least 1 inch of snow on the ground on December 25, using data from 1991 to 2020 from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

The map is based on data from nearly 15,000 weather stations across the country, with the intervening areas shaded according to interpolation—a method of estimating values where there aren’t direct observations.

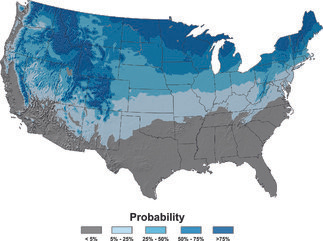

This graphic is an update to a 2015 analysis based on 1981-2010 data that was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society—like I said, people take this stuff seriously! Here’s the earlier map, which, unfortunately, is low resolution and uses different colors/categories:

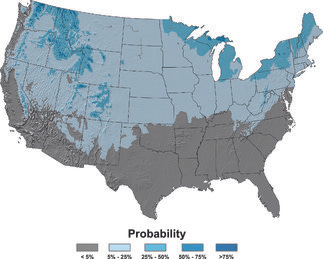

The 2015 paper also includes some additional maps, such as the one below showing the probability of at least 0.1 inches of snowfall (rather than snow cover) on December 25.

In the age of climate change, you might be wondering if warming temperatures are changing the odds of a white Christmas. Well, the time periods in the two analyses—1981 to 2010 versus 1991 to 2020—have 20 years of overlapping data, so it’s tough to tease out climate effects. Moreover, some places are typically well below freezing on December 25, so even though average air temperatures are rising, it might not be enough to cause raindrops to replace snowflakes.

“All that said, however, the spatial fingerprints of climate change that we’d expect based on our modelling studies are visible in national patterns of change in temperature and precipitation normals,” according to climate.gov, which notes that there are “some subtle differences” between the two maps:

More areas experienced decreases in their chances of a white Christmas than experienced increases. The easiest one to spot with the naked eye is the expansion of the dark gray area, where the chances of a white Christmas are less than 10%. The gray area shifted noticeably northward across the South, and upslope along the ocean-facing slopes of some of the West Coast mountain ranges. Beyond those broad strokes, local changes between the two maps would have to be carefully investigated and placed into context with other climate data and analysis techniques better suited for detecting long-term change.

At snow.news headquarters near Durango, it’s been a dry couple of weeks, so there’s now barely any snow on the ground. With few flakes in the long-term forecast, the probability of whiteness isn’t looking great for the Winter Solstice, Christmas, or the start of Hanukkah and Kwanzaa. Here’s hoping we don’t have to wait until New Year’s or MLK Day to see some more snow around here!