Reporter's notebook: 91st annual Western Snow Conference

Takeaways from a fascinating meeting that was all about the science. Plus a roundup of recently published studies and other snow news.

I got a crash course in snow science at my first Western Snow Conference.

The 91st annual gathering of snow researchers—held in April at Oregon State University in Corvallis—was a great way for me to learn about the field and meet snow experts.

The other conferences I’ve attended in recent years have covered water management, environmental journalism, and philanthropy, so they’ve been necessarily steeped in politics. There’s a lot of posturing and performing. People who sit on panels also stand on their soapboxes. Audience members make speeches instead of asking questions during the Q&A sessions.

So it was a real treat to be back at a conference that was all about the science. The research on our changing snowpack and altered runoff patterns certainly had political implications. At this meeting, however, the focus was on advancing our understanding of snow and providing more accurate information to the decision-makers who must grapple with messy, value-laden policy decisions about how all that snowmelt gets used downstream—and how snow-covered landscapes are managed.

The atmosphere in the Willamette Valley was collegial, inquisitive, open-minded—and oxygen-rich compared to my home in southwest Colorado. It was refreshing to adopt the posture of a curious student eager to learn about the physics of snow, the complexity of our climate, and the phalanx of technologies that scientists deploy to study the snowpack: satellites, planes, drones, radar, lidar, spectroscopy, fancy weather stations, and good old-fashioned manual measurements collected on skis and snowshoes.

One striking thing about OSU is the fleet of six-wheeled robots that prowl the campus to deliver food, beverages, and other items. With a few taps on an app, I ordered my lunch and was met 15 minutes later by the contraption—a reminder of the stunning pace of innovation that is also helping researchers grasp slippery concepts in snow science.

The inaugural snow conference way back in 1933—called the “Western Interstate Snow Survey Conference”—was the brainchild of James E. Church, a professor at the University of Nevada Reno who invented the metal tube snow sampler that’s still in use today. The February 1933 meeting in Reno included 40 people from Nevada, California, and Utah, but “representatives from southern California were blocked from attending by snow,” according to the history page on the conference website.

Should you teach your grandkids to ski?

This year’s keynote was delivered by Philip Mote, a noted snow researcher who is also vice provost and dean of the graduate school at OSU.

In his presentation, “Should I Teach My Grandkids to Ski? An Examination of Climate Change and Snow in the Western US,” Mote shared some of the troubling findings from his and others’ research, focusing on the Pacific Northwest.

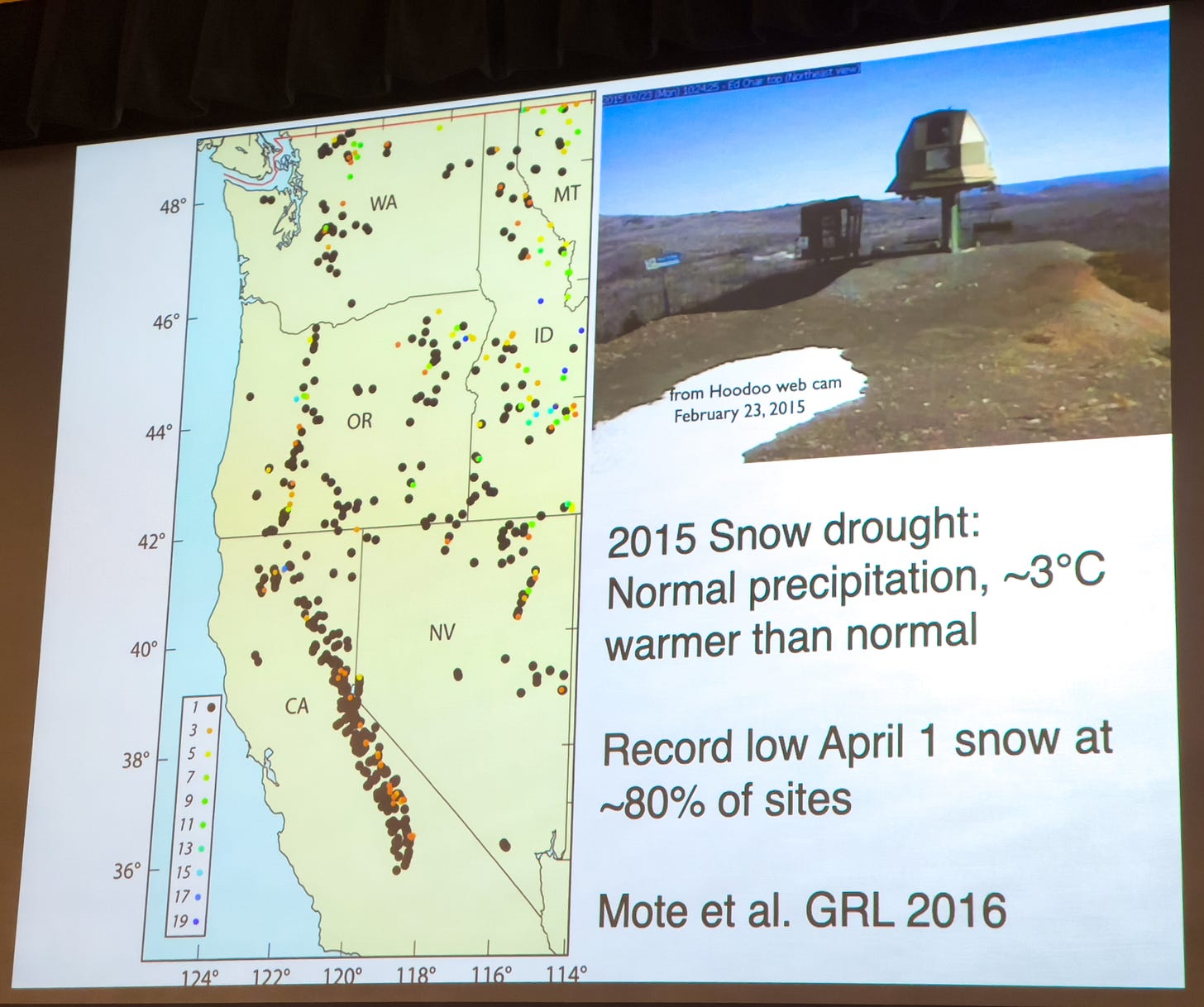

Mote’s most widely cited paper, according to Google Scholar, is a 2005 study, “Declining mountain snowpack in western North America.” The photo below of one of Mote’s slides shows data from a 2016 study he co-authored, “Perspectives on the causes of exceptionally low 2015 snowpack in the western United States.” All those black dots on the map indicate record-low readings for the April 1 snowpack.

The photo in the slide shows the bleak picture at the top of a chairlift at Oregon’s Hoodoo Ski Resort on February 23, 2015. “There was also a photo of someone kayaking on a puddle at the base of one of the lifts,” Mote said.

While warming has already taken a toll on the West’s snowpack and further reductions are expected, Mote answered “yes” to the question he posed in the title of his talk.

Here are the bullet points from the final slide of his presentation. In the sub-bullets, I’ve added some quotes from Mote and comments from me.

We are no longer following RCP 8.5

RCP stands for Representative Concentration Pathway, and 8.5 is a pessimistic emissions scenario that now seems implausible given the pace we’re decarbonizing the global economy. “That’s a bit of good news,” Mote said. “I’m not saying you should fly all over the world emitting carbon in order to go skiing, like I know some people do. That would put us back on a path to RCP 8.5.”

Observed and projected losses in snow in winter are smaller than in spring

The late-season snowpack is more vulnerable “in part because of the increasing role of warming in reducing spring snowpack, both through reduced snowfall and increased ablation,” Mote said (“ablation” is the loss of snow through melting, evaporation, sublimation, and other processes).

Increases in precipitation offset some of the warming-induced losses

The marquee matchup for the future of the snowpack: a warmer atmosphere can “hold” more water vapor versus warming making it more likely that raindrops will replace snowflakes.

Ski areas tend to be in less vulnerable parts of mountain ranges

“They tend to be at higher elevations and many are in bowls or other protected places where they’re not just baking in the sun all day long,” Mote said. “But that’s not to say that everything is hunky-dory.”

But . . . some ski areas are in trouble

Lower-elevation resorts are in more jeopardy. In the Pacific Northwest, “there’s probably a dozen ski areas where the future is very much in doubt,” Mote said.

Introducing the “snow deluge”

We’ve heard a lot about “snow droughts” lately, but scientists are also interested in big snow years.

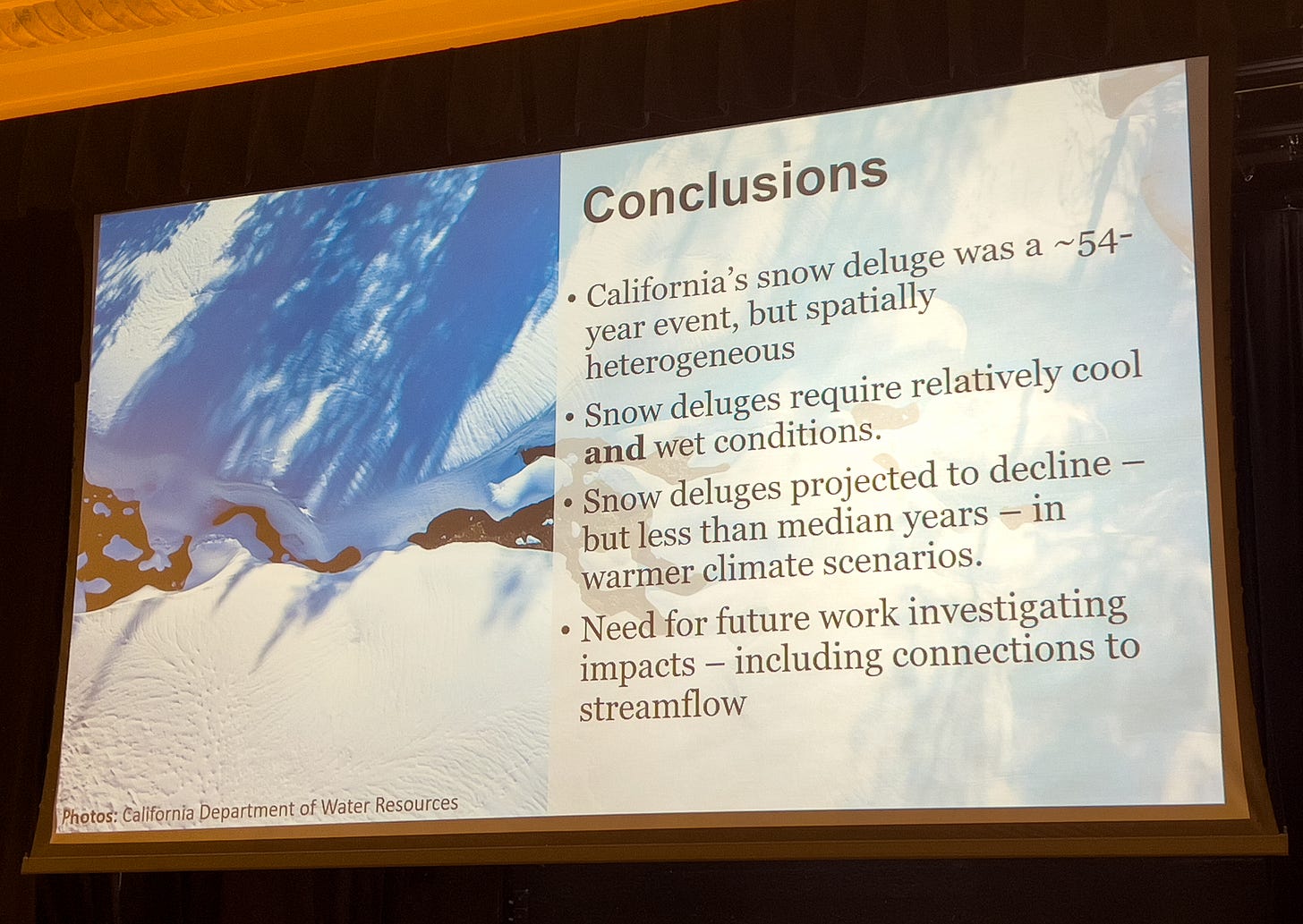

Adrienne Marshall, a scientist at the Colorado School of Mines, presented findings from an April paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that she co-authored on “snow deluges,” which the researchers define as a 1-in-20-year event for April 1 snow water equivalent.

The study focused on the 2023 water year in California, which set records for the snowpack in many places. That wet, cold winter busted a severe drought, but the scientists project that such snow deluges will become less frequent in the decades to come because warming will make it more likely for rain to fall instead of snow.

I recently interviewed Marshall and will soon publish my Q&A. The photo below of her conclusions nicely sums up the study, which estimated that California’s epic snowpack was a 1-in-54-year event.

The reservoir manager’s bind

I love visuals that elegantly summarize complex problems or decisions. So my eyes lit up when hydrologist Gabe Lewis showed the flow chart below on one of his slides during a talk on flood forecasting in the Sierra Nevada. It neatly illustrates a fundamental dilemma that reservoir managers face in handling the earlier runoff of snowmelt due to climate change. Is it a hazard or a resource? Choose your own adventure.

As the flow chart shows, a manager might want to release more water downstream to preserve space in a reservoir, fearful that an early onslaught and wet weather will create flooding problems down the line. If, however, the weather winds up on the dry side, there will be no flood to worry about, but there will be less water available for later in the year.

Conversely, a reservoir manager who sees the earlier runoff as a resource might choose to store that water for later use, which is great if there’s no flooding. But that’s a potentially deadly and disastrous strategy if the reservoir runs out of room.

This stuff is complicated

To be honest, plenty of material at the conference flew over my head, leaving me to engage in a running sidebar conversation with ChatGPT as I tried to define a blizzard of acronyms and terminology while refreshing my knowledge of science and statistics.

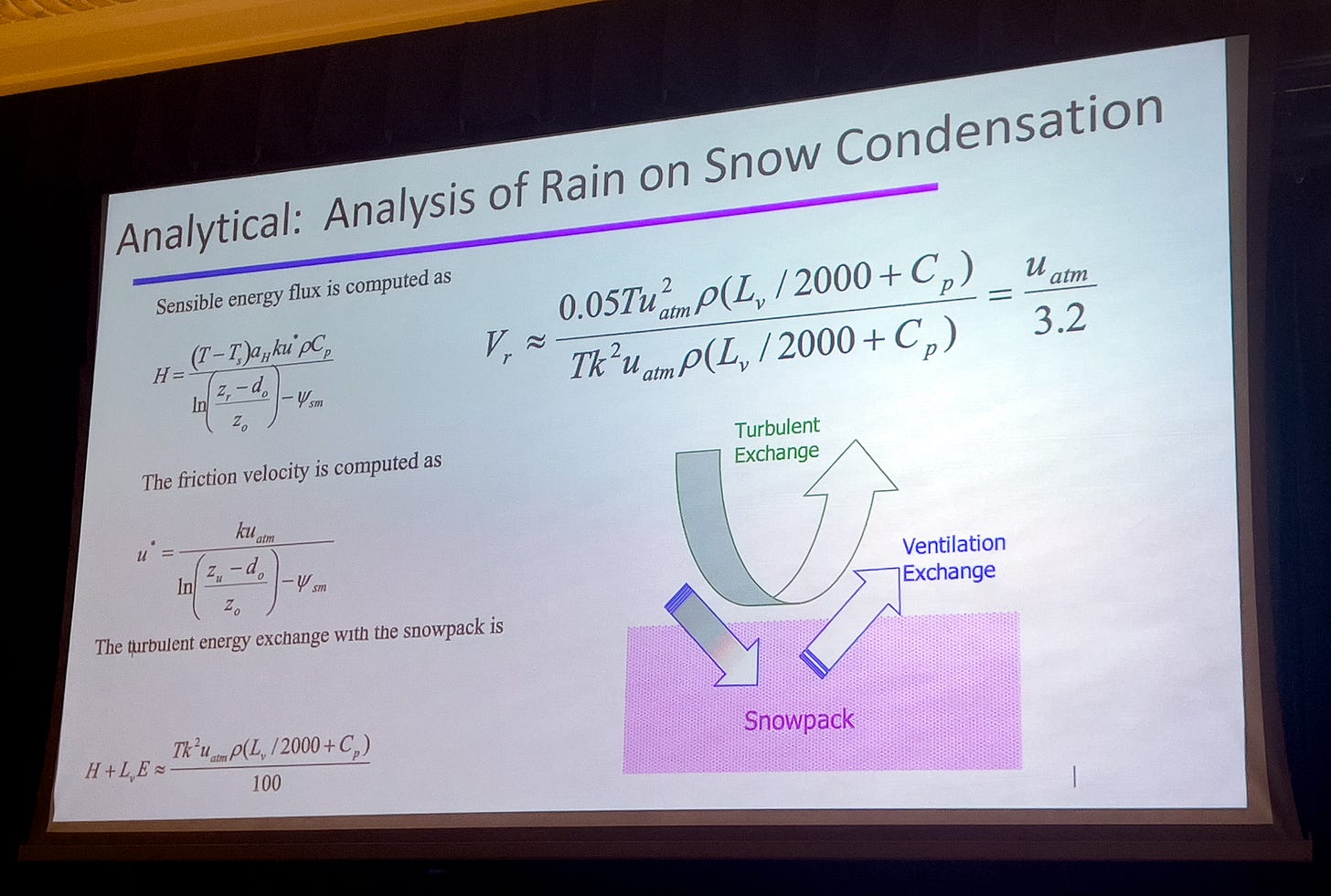

Below is one of the more intimidating slides, from a presentation about rain-on-snow events, which can unleash major floods and are likely to become more common due to climate change.

One of my takeaways from the conference—and from my work thus far on Snow News—is that snow science is way more complicated than my layman’s brain had conjured.

Nearly a century after the first Western Snow Conference, and despite an explosion of technology and knowledge, we still struggle to precisely measure how much snow is out there because the snowpack varies so widely and deeply across the landscape, making it tough to gauge conditions over a vast region.

Take a look at the photo below, a view of the Sawatch Range in central Colorado from the window seat on the Durango-to-Denver leg of my journey to Oregon. Imagine how difficult it would be to calculate the volume of snow and water beneath you. And this view shows terrain above treeline on a clear day, eliding the confounding factors of a forest canopy and cloud cover.

Snow news roundup

Below are summaries of five recent stories about snow that I found interesting.

Mountain goats are not avalanche-proof

Lesley Evans Ogden, The New York Times, 5/1/24Turns out that avalanches kill lots of mountain goats in Alaska and can be a major driver of population changes. That’s the conclusion of a recent study in Communications Biology based on nearly two decades of research. “Data from the collared goats revealed that snow slides barreled down not just on inexperienced kids but on breeding adults as well, especially females in their prime,” Evans Ogden writes.

The mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus). Source: Alaska Department of Fish and Game. A rare dose of hope for the Colorado River as new study says future may be wetter

Alex Hager, KUNC, 5/5/24

A new study about the Colorado River in the Journal of Climate forecasts “a 70% chance the next quarter century will be wetter than the last,” and researchers say “that could be big enough to offset the drying caused by rising temperatures, at least in the short term,” Hager writes. These projections run counter to other research and a scientist not involved in the study expressed some skepticism.Another fast, early melt in the southern mountains

Russ Schumacher, Colorado Climate Center, 5/8/24

In southern Colorado, “it’s been another year where the melt has happened a lot faster than it typically has in the past,” writes Schumacher, the state climatologist. Several basins suffered record-setting losses of snow water equivalent in April. “It means higher-than-normal streamflows in May, but then much lower streamflows later during the heat of summer, when the water is really needed, especially by those who don’t have access to water stored in reservoirs,” he writes, adding that “unfortunately, years like this have been getting more common, and that trend is expected to continue as the climate warms.”

Secrets of the “subnivium”: arthropod community thrives beneath winter snowpack

Melissa Mayer, Entomology Today, 5/8/24An April paper in Environmental Entomology analyzed the forest floor in New Hampshire to learn more about the flies, spiders, beetles, and other arthropods that live beneath the snowpack. The scientists “found that the space between the soil surface and the snowpack—called the ‘subnivium’—is a refuge for arthropods, including some specialized to live there,” Mayer writes. The researchers, who collected more than 20,000 specimens, note that the winter arthropod communities are “highly likely” to diminish as climate change shrinks the snowpack in temperate and boreal forests.

This pioneering study tells us how snow disappears into thin air

Alex Hager, 5/10/24

Sublimation occurs when snow changes from a solid to water vapor without first turning into a liquid. Scientists and water managers want to know more about the process and how it affects runoff. An April paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found that less snow was lost to sublimation than expected. “Perhaps most critical in the new findings is the fact that most snow evaporation happens in the spring, after snow totals have reached their peak,” Hager writes.